ARTISTS TELL US MORE ABOUT THE METHODS AND MYSTIQUE OF THE PORTRAIT-MAKER’S ART

by Edward M. Gómez

In last month’s issue (June 2022), we published an introduction to the portrait-maker’s art, calling attention to our fascination not only with the various techniques that artists have developed to offer faithful likenesses of their subjects, but also with the uncanny ability some of the most skillful portrait creators seem to have when it comes to capturing in a painting, drawing, sculpture, or other work the intangible, emotional-psychological or even psychic energy of their subjects.

Call it the aura of any individual an artist might attempt to depict, that ineffable quality associated with any human being that informs and is reflected through his or her personality, speech, gestures, and disposition. It’s any person’s perceptible sense of presence.

Now, continuing our examination of the portraitist’s art and expanding the portfolio of portrait works we presented in the first part of this article earlier in June, here are some more images from various artists that further illuminate just what they’re up to — and displaying something of the endlessly diverse range of inventive and often ambitious approaches to their task these image-makers have taken, and the methods they have employed.

Holly Warburton (Instagram: @hollywarburton_official) is a British artist who divides her time between studios in London and in France. A graduate St. Martin’s School of Art (now Central Saint Martins College of Arts and Design, a division of the University of the Arts, London) and the Royal College of Art, over the years she has explored painting, photography, and film, sometimes bringing these genres together and, more routinely, experimenting with mixed media. Warburton told brutjournal: “I have loved to draw as long as I can remember, and portraiture has been a big part of my art.”

In the past, while creating mixed-media installation works, she developed, as she put it, “a photographic portraiture technique in the darkroom” by “projecting transparencies through painted glass onto canvas, which I painted and rephotographed.” She explained, “Sometimes I would print these multilayered photographs and paint on the print. I loved working with projected light on a painting or drawing, with photography combined. I made lots of works using this technique and was commissioned to make portraits of musicians and for record-album covers or the theater, the ballet, and the opera.”

Whatever Warburton and her muses are up to, they seem to be scoring some aesthetic-technical successes with surgical precision. The artist observed, “Sometimes I begin with automatic drawings with my eyes closed, which brings me closer to the feeling of the subject. I am a beekeeper and I love to draw with pencil, beeswax and inks. Recently, I have been drawing portraits from life. I went to join a lovely life drawing group, where the model dressed up as the Elizabethan magician and alchemist John Dee. Sometimes meditation and dreams can help inspire a portrait; sometimes I manipulate the photos I take to bring out the emotional-psychic energy of a person, while, other times, I choose a subject to photograph who represents the human qualities or feeling I want to express in a work.”

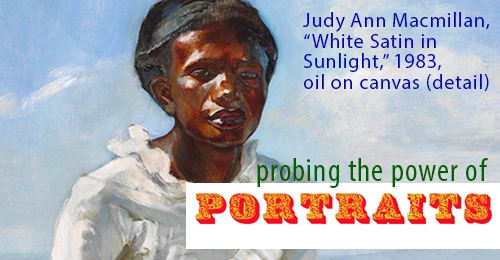

Judy Ann MacMillan, an artist who was born and brought up in Jamaica, where she has lived almost all of her life, is now in her early 70s. In her richly evocative — and very funny — memoir Born Ya: The Life and Loves of a Jamaican Painter (Beattie Books, 2019), she recalls her experiences as she has tried to develop and nurture a career as a serious artist in a tiny island country whose art market and related institutional infrastructure are almost nonexistent. Nevertheless, MacMillan has become recognized in Jamaica and the broader Caribbean region as something of a doyenne among portraitists. From her studio in Kingston, Jamaica’s sun-soaked, traffic-clogged capital on the south side of the island, she sent us a note.

About “Village Venus,” MacMillian’s large, vertical-format oil painting that appears above, the artist noted, alluding to her country’s complex and inescapably patriarchal and sexist social system, “The young woman depicted here may be seen as representing an example of a sex symbol from the village down at the bottom of the hill, near my home in St. Ann, in the north of Jamaica. In this respect, she embodies all that a typical man in the village desires.”

MacMillian recalled the day her model first arrived at her studio to sit for this portrait. The artist stated, “I noticed the change that came over my gardener/caretaker when she was on the property. He was shaken by her seductive appearance, and I was interested in that power — and a little amused — so I gave her a little tiara decorated with Disney princesses to wear in order to visually emphasize this point. As a portrait, this is a good likeness, but for me, in this case, this aspect is secondary, for this picture is perhaps more about the phenomenon of feminine allure — a portrait of that power, which varies from culture to culture but in this instance, this picture represents its particular expression in rural Jamaica.”

As an experienced practitioner of her specialized métier, we were interested in MacMillan’s observations about that invisible something that makes the most memorable portrait a strong one. She told us, “Everything comes from the visual effect of the thing seen — all ideas, changes of ideas, or new directions in one’s thinking are unself-conscious responses to what I find, for want of a better word, beautiful in looking at people. The painting emerges out of that emotional experience, so I’m painting my own emotions, my own response to the subject, and that human connection, that exchange, is what gives a portrait its truth.”

Based in London, the artist Melissa Alley has sat in a church and drawn pictures of the person seated next to her, developed new images based on photos from 19th-century cartes de visite, and explored the methods of mediumistic art. She told brutjournal: “Fifteen years ago, I trained with a medium in her circle, where I would make drawings based on the people she invited [to take part in séances]. My hand knew what color to pick up and what mark to make, and soon I was reading the information held in these ‘auragraphs,’ which reflected the lives of their subjects so well.” Alley’s mediumistic portraits of the deceased tend to be abstract in character.

About her working methods, she noted,—I have brought that same skill into my studio practice and my work [coming from] many [sources of] inspiration, such as antique portrait photographs, a recording of a conversation, ‘engagement slips’ [indicating the employment status of workers at] a foundry in the 1920s, or chatting over the phone or [in in-person] sittings. My portraits tend to reflect the whole person — [his or her] physical, spiritual, and emotional lives.”

Alley’s work will be on display in the gallery at Thames-Side Studios in London, from July 2 through July 9, 2022. (Address: Unit 4, Harrington Way, London SE18 5NR.)

The artist Mark Milroy, whose work we introduced in part one of this article, teaches portrait painting at the National Arts Club, an organization founded in New York City in 1898 by Charles DeKay, an art and literary critic of the New York Times. Its purpose: to “stimulate, foster, and promote public interest in the arts and to educate the American people in the fine arts.”

Milroy’s images tend to flatten the contours of their subjects, diminishing to a certain extent the role of modeling in depicting their three-dimensional forms and allowing color, shapes, and accentuated details to evoke the spirit of their personalities; his portraits strive to capture the essence of their subjects while seeming to simultaneously use them as jumping-off points for explorations of various technical or subtly expressed thematic ideas — and, if so, why not?

Milroy told us, “I still find working with the simplest of materials — pencil or charcoal on paper, or oil on canvas — to be humbling and forever interesting. It’s like what the writer Henry Miller said about when you look at a nose or an ear, and suddenly you don’t see just an ear or a nose but instead a whole universe of shape, form, and color.”

For some time now, Milroy has been writing short texts that he calls his “narratives,” some of which he has gathered together in I Do Not Understand, a chapbook illustrated with his own pictures that is available through his personal website. While these anecdotal writings reflect what the artist refers to as his attempt to comprehend his evolution as an artist, in fact, viewers may sense after surveying a good portion of his larger body of work — portrait paintings, drawings, prints — that an unsinkable sense of wonder about the magic of making art is as much one of his abiding subjects as are the more obvious themes of the many different images he has created over the years.

The artist and musician Tim Kerr was born in 1956 and has spent most of his life in Austin, Texas, where he studied painting and photography at the University of Texas. Decades ago, after graduating from U.T., he became involved with the nascent DIY hardcore/punk scene and went on to perform and record with various bands for independent record labels, and then to produce recordings for many of those same companies.

Working from photographs, over the years Kerr has produced portraits — on such surfaces as wood panels and skateboards — of many well-known musicians and cultural or political figures, including, among others, the jazz saxophonist John Coltrane, the blues guitarist and composer Lightnin’ Hopkins, the soul and jazz poet Gil Scott-Heron, and the American outsider artist Howard Finster. Several years ago, in an interview with a ’zine aimed at skateboarders and fans of indie bands of hardcore/punk lineage, Kerr noted that many of the individuals whose portraits he chooses to paint have been those who helped inspire others to seek “positive change” and to take “positive action[s]” to create a better world. Kerr’s portraits are now on view in a solo presentation at Webb Gallery, a venue in Waxahachie, Texas, a small town just south of Dallas, which has long specialized in works made by American outsider artists and other notable mavericks.

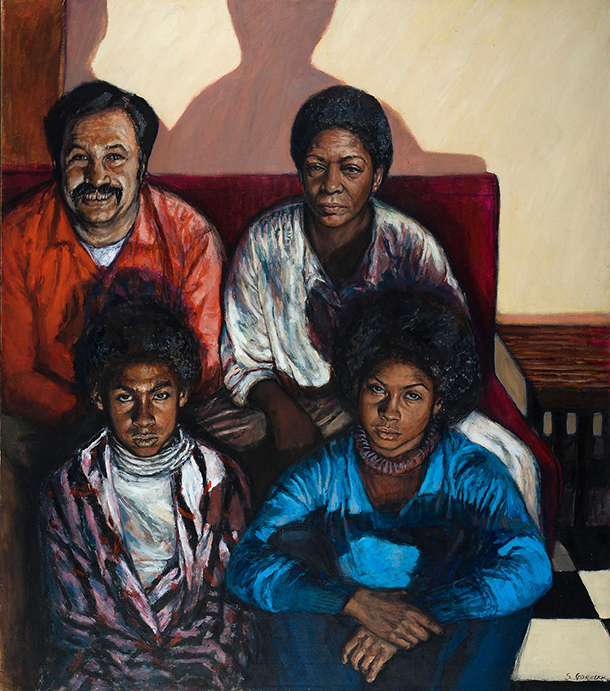

In New York, Eric Firestone Gallery’s Manhattan branch (at 50 Great Jones Street) has just opened Shirley Gorelick: Family (on view through July 29) featuring a representative selection of the canvases of a painter who was known for her vivid portraits, in which the psychological probing of her subjects can be unmistakably felt. Collectors and art historians who are familiar with Gorelick’s work have also appreciated the female point of view her pictures convey; the artist, who was born in New York in 1924 and studied with the sculptor Chaim Gross and the painters Moses Soyer and Raphael Soyer, worked from live models and photographs, eschewing a completely abstract approach or one that aimed for photographic exactitude in capturing a subject’s likeness.

If Gorelick’s command of her materials and painting technique allowed her to portray her sitters with remarkable verisimilitude, the self-taught artist William Dawson (1901-1990), who made paintings on board and carved-and-painted statuettes, depicted his own subjects in a manner that at first might appear repetitive and generic but which, when examined again, reveals striking expressive differences and details. The depth of an incision here to shape a carved face or the gentle coloring there to define the contours of a cheek suggest that Dawson, who moved from his native, rural Alabama to Chicago when he was a young man and spent the rest of his life in the northern Midwest, was a life-long people watcher whose body of work exudes a deep sense of empathy and humanity.

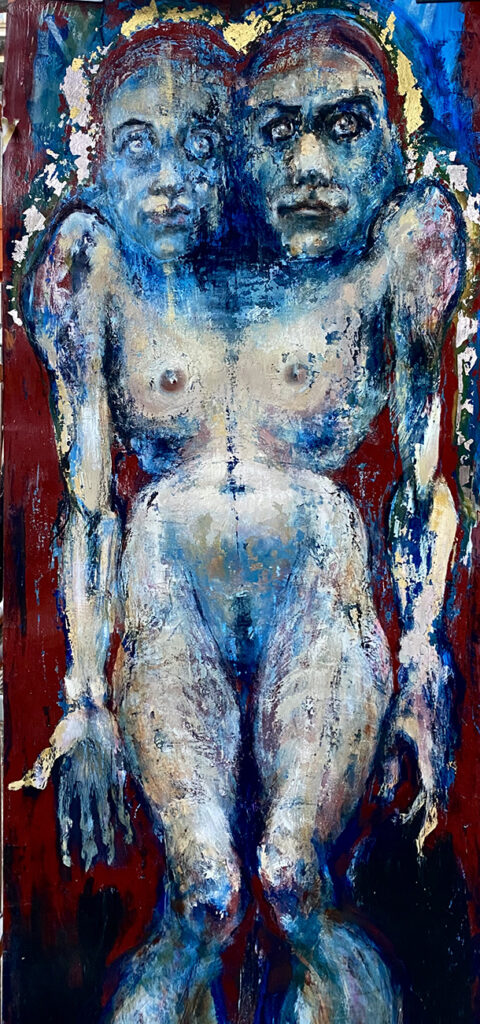

Years ago, the artist Cathy Ward, who is known for small- and large-scale, mixed-media paintings in which, using a scratchboard technique, she incises into black-painted surfaces to reveal luminous white lines that gather into voluminous tufts or roll out like unfurling skeins of long, silky hair, made a strange self-portrait (above). Titled “Friends,” it depicts the artist as a two-headed woman gazing out at her viewers.

In a recent e-mail exchange, Ward recalled, “At the time I made this painting, I was mainly sculpting in plaster and clay, creating hybrids and mythical-type beings by playing around with anatomy. ‘Friends’ was my inaugural attempt at painting a psychological self-portrait. My religious background being Roman Catholic, I was — and, in fact, even today I remain — obsessed with religious iconography related to spiritual ecstasy, self-sacrifice, martyrdom, death, and a body’s putrefaction. I made this painting at a time of hysterical paranoia surrounding HIV infection and dying from AIDS. In this self-portrait, I was wrestling with a few of my own neuroses regarding sexual identity and a heightened sense of alienation.”

Elsewhere in this issue, we look at how the photographer Bill Westmoreland has been creating not just generic images of animals of the kind that are normally found in news reports about nature or rural getaways, but instead what can genuinely be regarded and appreciated as portraits of specific cows. (See brutjournal’s article about those photos here.) He has been shooting his photos in a part of Pennsylvania that is home to many dairy farms.

Recently, while working on another photo project, Westmoreland found himself tinkering with paint to come up with a backdrop emulating super-bold Yves Klein Blue, a color invented — and patented in France in 1960 — by the French conceptual and proto-performance artist Yves Klein (1928-1962). Rich in ultramarine, Klein’s signature hue was used in abstract works he painted in a most unconventional manner, covering the naked bodies of female models with his bright color and then having them roll around on blank canvases.

Westmoreland did not put any cows through any such exercises for the sake of art. Manipulating his photographic images digitally was enough to achieve the results he came up with, yet another example of the endlessly intriguing art of the portrait.