DO SOME WORKS OF ART POSSESS — AND EXUDE — SPIRITUAL ENERGY, AND DO SOME PROVOKE TRANSCENDENT EXPERIENCES?

by Edward M. Gómez

In these most dispiriting times, art in all its forms — including visual art, music, literature, theatrical productions, movies, and more — often seems to provide the kind of solace and inspiration that even the most cherished friendships, intimate relationships, or family ties cannot provide. Maybe they are just too earthbound or rooted in the troubled, uncertain reality from which art, among other rewards, offers what the modern British writer Graham Greene, who suffered since childhood from depression, called “ways of escape.”

For some, religion, immersion in sports or hobbies or studying, or other kinds of diversions may provide both satisfaction and a sense of grounding. For others, art, the artistic life, or an artistic outlook on and approach to living may offer a firm anchor in life’s perpetual storm.

As far as visual art is concerned — a simple or complex picture; a modest wood carving or one of Rodin’s hunky, brooding bronzes — why is it that some artists’ creations seem to radiate a tangible force that is something more than the sum of their constituent parts, a kind of energy that flows from them even as it envelops them in invisible fields of irresistible allure? It’s the energy that animates and flows from the eyes of da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” or from those of an ancient Egyptian, carved-stone sarcophagus, with its look of eternal contentment.

Peering even farther back into the past, it’s the inexplicable life force that can be felt in the charcoal-stick and simple-pigment pictures made by our prehistoric ancestors on their caves’ interior walls, nascent civilization’s first baby steps in the development of visual culture and the unmistakable, enduring testaments of self-conscious beings who, with their jottings, declared for posterity, “We were here.”

Art that exudes a certain kind of soul-stirring energy, that seems to emerge from or send out signals from the psychic depths, and that pushes us toward the spiritual — this is the kind of art we’re examining this month in a special collection of articles and photo essays.

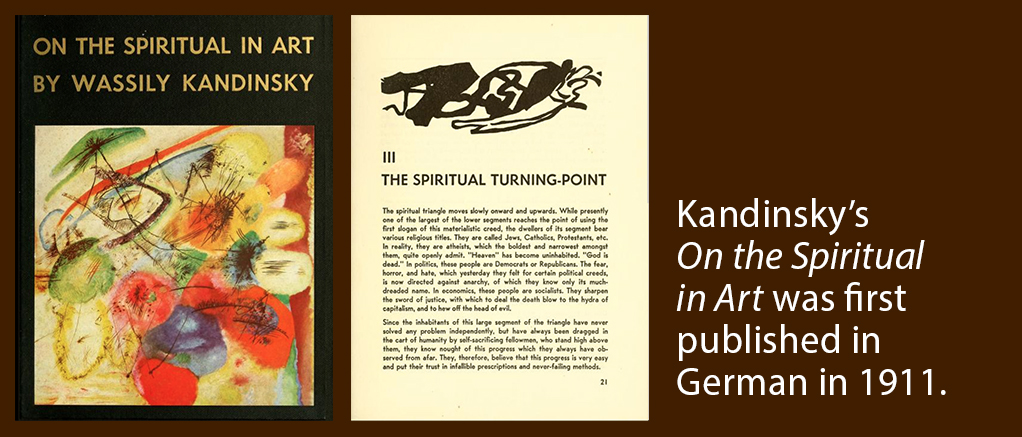

In his book Über das Geistige in der Kunst (On the Spiritual in Art), which was first published in German in 1911, the pioneering modern artist Vasily Kandinsky (1866-1944), observed that the “nightmare of materialism” had “turned the life of the universe into an evil, useless game.” He proposed that, through their work, artists not only could but should aspire to help lead humanity toward a pinnacle of spiritual experience and fulfillment. When an artist’s creations are “truly artistic” and “fulfill their purpose,” they have the potential to “become food for the spirit,” Kandinsky asserted.

For many artists, to be aware of and to find pleasure in the creative process is its own spiritually fulfilling reward. The painter Alma Realm, for example, who lives and works in northern Minnesota, and is known for her bold palettes and broad, economical brushstrokes, sent us photos of some of her pictures which, she felt, relate to the spirit-and-spirituality theme.

Sounding like a hermit monk who looks for and, if he’s lucky, finds inner peace, enlightenment, or the spiritual equivalent of winning the lottery, Realm shared this note about her painting “I’m Not Really Here” (2022): “I’m not really here. I’m just a vessel of my thoughts, which I give to you, and ask in return only to be left alone.” For some seekers, thinkers, or creators, to be able to live and work in solitude constitutes a rewarding transcendent experience in its own right.

For the American artist Michael Newman, whose work and career were the subjects of an article in brutjournal’s March 2022 issue, the language of abstraction has long served as a springboard to rewarding aesthetic-spiritual experiences. Newman, who now lives in Taiwan and in the past spent many years in Japan, enjoyed his first encounters with the classic art of Asia in the study collection at the legendary Rudolph Schaeffer School of Design in San Francisco, where he was a student in the mid-1960s.

Recently, Newman told us, “For me, art, life, and spirituality are one and the same. Although the same work of art might be seen in different ways by many different observers, each of whom will bring his or her own social or other values or myths to the experience, there are certain things that we see, feel, and touch that are shared, that are within all of us, and art taps into that shared knowledge or sense of perception.”

We got in touch with the painter Miles Cleveland Goodwin, who lives in a small town in north-central Georgia, right on the border with Tennessee. Goodwin is known for pictures of animals and the land that evoke a sense of primordial existential awareness. (Think Anselm Kiefer on a smaller, more intimate scale, without all the modern-history-laden Sturm und Drang; in Goodwin’s art, the sense of history he evokes is more that of Jung’s collective unconscious.)

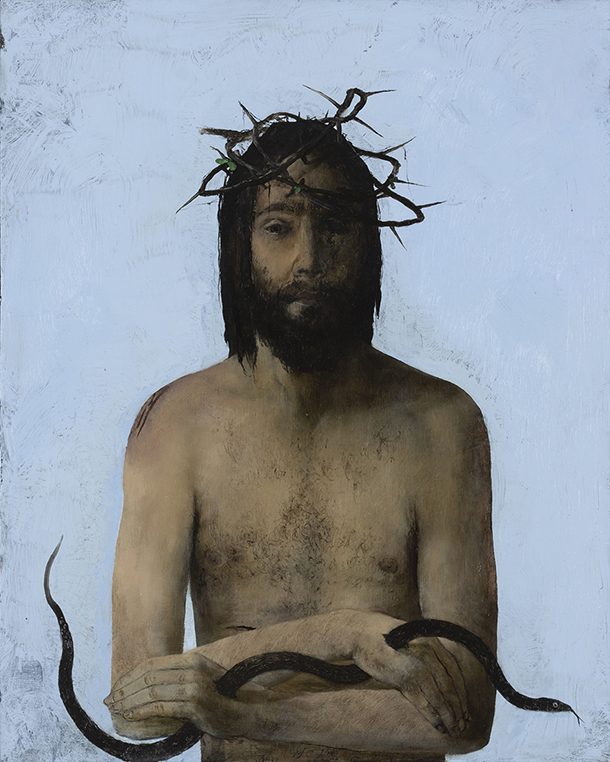

In some of his more recent works, Goodwin has included familiar Christian iconography, but usually with an unironic, earthy twist. His slender, bearded Jesus, his head topped with a crude crown of thorns, looks like a tired grunge kid who isn’t quite sure about his divine status and would be glad to exchange the pesky snake that is slithering through his hands — its stringy body literally pierces them — for a cold beer and a warm place in which to lie down and take a nap.

Goodwin noted, “Through my work, I’m always attempting to address my own concerns about the spiritual. While I do not view painting as something I do solely for myself, I do believe that a person’s experience of God and the spiritual world is a highly personal and individual experience. Through my work, I hope to create places and situations that may provoke viewers to reflect on the meaning of their own lives.”

In this issue, we meet such artists as the California-based Reda Rackley (also known as “Bonewoman”), who dips deeply into her personal history to find inspiration in the stories of her female ancestors’ perseverance and survival; the Japanese artist Fumio Shiozawa, who has taken a new approach to depicting ancient Buddhist deities; and Judith McNicol, a British maker of psychologically intense drawings and mixed-media assemblages depicting fantasy birds. As a geologist, McNicol made some on-location field trips away from her university, and later she became a neurosomatic therapist, but her most far-reaching journeys have been to the depths of the psyche — her own. Her art is the expression of a personal spiritual quest.

We also hear from brutjournal’s London-based artist-correspondent Cathy Ward, who tells us about the development of her “Rite of Passage” series of abstract works inspired by memory, psychic energies, and a sense of moving toward the spiritual through the creative process and, ultimately, through interactive dialog with art.

(The sixteen units of Ward’s “Rite of Passage” series are now being offered as premiums along with brutjournal’s Option 3 subscription package. See the magazine’s SUBSCRIBE page for details.)

We also examine the mixed-media figures, inspired by the principal characters of the tarot deck, of the artist Angela Rogers; the history of the spiritualism movement, as recounted by the specialist in folklore history, Daniel Wojcik; and the phenomenon of so-called spirit photos (with a selection from John Foster’s superb collection), which date back to the early decades of photography’s evolution. In a photo-portfolio exclusive, the photographer Bill Westmoreland, brutjournal’s visual director, has reimagined 19th-century “spirit photos” and conjured up some new ones, with a contemporary vibe, for modern mystics.

Through these articles and photo essays, we dive into the relationship between art and the spiritual, the spirit world, and spirits of various kinds. In these discouraging times, the message that emerges from much of the art we examine here couldn’t be more uplifting as it offers our collective, sometimes weary spirit a simple, unhesitating word of advice: Soar!