AN AMERICAN ARTIST BLENDS INK-WASH TECHNIQUES AND MODERNIST ABSTRACTION IN A SOULFUL STYLE OF HIS OWN

by Edward M. Gómez

Nowadays, it seems, many contemporary artists still have not received, read, and responded to the memo. Which one?

The one that went out some time ago informing them that now-tired postmodernist detachment and calculated irony are dead, and that sincerity, authenticity, and the expressive power of fine craftsmanship — of what they can say through their own skillful handling of their materials instead of sending their designs out to be produced for them by fabricators — is in.

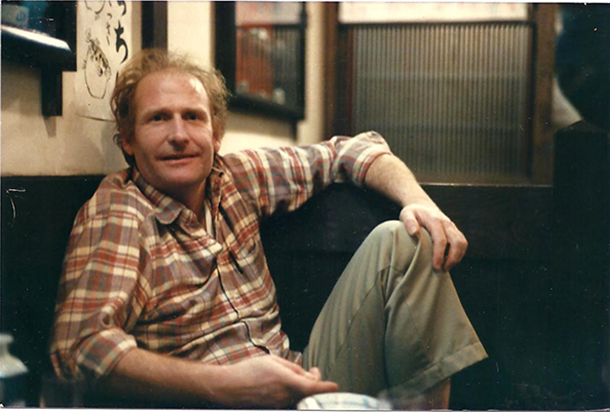

With this in mind, for many years I’ve been following the development of the work and ideas of the American painter Michael Newman, whose life journey has taken him to Asia many times and whose focus on a fine balance between the technical and the communicative aspects of his art has become a hallmark of almost everything he creates.

Born in Berkeley, California, in January 1945, Newman grew up in the countryside around San Francisco long before it was overtaken by suburban sprawl. As a young man in the early 1960s, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was sent to Japan; more than a decade had passed since the end of the postwar, U.S.-led Allied Occupation of that war-torn country, which was vigorously rebuilding its economy and shattered cities, and developing the infrastructure and institutions of a modern democracy.

After returning to San Francisco, in 1966 Newman enrolled at the now-legendary Rudolph Schaeffer School of Design. Originally known as the Rudolph Schaeffer School of Rhythmo-Chromatic Design, it was founded by its namesake in 1924 and closed in 1984. Schaeffer (1886-1988) was a Michigan-born artist who was associated with the Arts and Crafts movement and became known for his insightful teachings about color and design. A notable aspect of his school’s curriculum was its accent on the art and philosophical traditions of Asia. In its study collection, actual examples of older Asian art forms were available for students to examine.

Against the backdrop of the hippie movement and the tumultuous social-political events of the 1960s, and as Pop art and psychedelic rock erupted on the cultural scene, Schaeffer’s school provided something of a refuge in the storm for young artists like Newman who had become intrigued and inspired by Asia and wanted to learn more about its artistic traditions. At the same time, certain influences from Asian cultures, from transcendental meditation to Mao jackets and the sound of the sitar, were making their way more superficially into Western pop culture.

In a recent interview with brutjournal, Newman, who now lives in Hualien County, in eastern Taiwan, where he teaches at National Dong Hwa University, recalled, “At Schaeffer’s school, I did everything to help cover my costs. I basically lived there. I cleaned the toilets, the rooms, the garden. Schaeffer had a very good Asian art collection, and I was able to handle the artworks daily — actual objects from Chinese and other ancient Asian dynasties. I drank up inspiration from them, and they even inspired my dreams.”

He said, “Through them, I began to see and understand abstraction in Asian art and, in turn, abstraction in other forms in all of the arts. This understanding continues to influence my work today. Schaeffer taught his students to appreciate touch and texture, to savor color, and to recognize the light in and from an object like, for example, a Song Dynasty vase, or to feel the sensuous lines of a Han dynasty wooden sculpture.”

At Schaeffer’s school, Newman studied the fundamentals of design. He learned to use watercolor and was introduced to Asian ink-wash painting (using brushes and ink to make paintings on paper). He studied with a painter who used Japanse sumi ink and learned about scroll-mounting techniques. Around this time, Newman became familiar with the ideas and work of such painters of the formative periods of abstract art as Wassily Kandinsky, the German painter August Macke (a friend and colleague of Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Robert Delaunay), and the American painter Mark Tobey (1890-1976), whose dense compositions were themselves inspired by Asian calligraphy.

“It was my education at Schaeffer’s that prompted me to return to Japan,” Newman recalled. After graduating from the school, he headed back to Japan in the early 1970s, deeply engrossed in the writings of the Indian-born philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986) as he made his way across the Pacific as a passenger on a freighter.

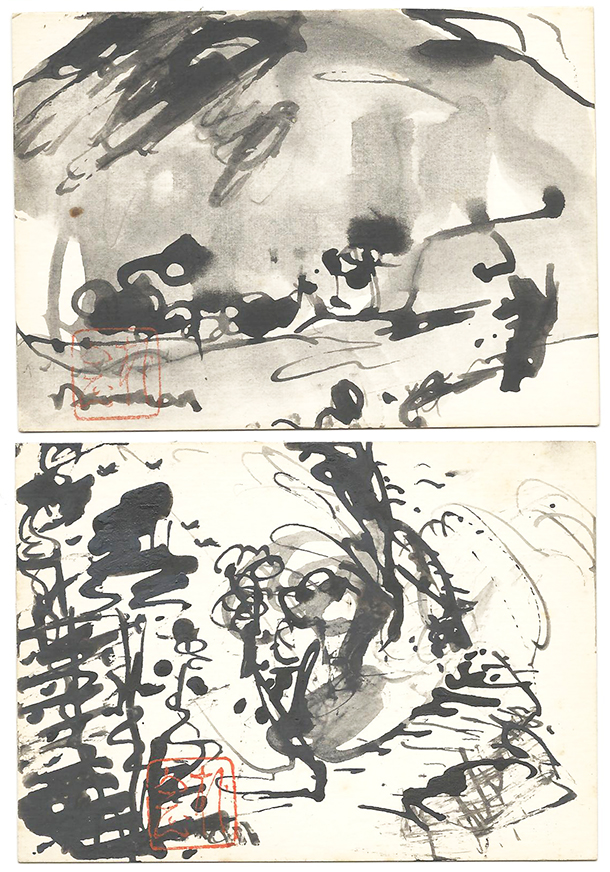

After reaching his destination, Newman studied the nanga style of sumi-e painting in Kyoto with the artist Shūson Kōno. The works of the Japanese nanga master Uragami Gyokudō (1745-1820), a calligrapher-painter who was known for the scratchy look of his landscapes, became models for the kind of art, blending a refined technique and a solid understanding of nature’s textures and forms, that Newman aspired to produce himself.

After his Japan sojourn, the young artist returned to California, where he went on to earn a degree in fine art from the San Francisco Art Institute. The year was 1974. The previous year, President Richard Nixon had signed the Paris Peace Accords, officially ending direct U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Now, Newman’s deeper, life-long engagement with the art and cultures of the East would begin in earnest, for following his graduation from the art school, he headed back to Asia and eventually settled in Japan.

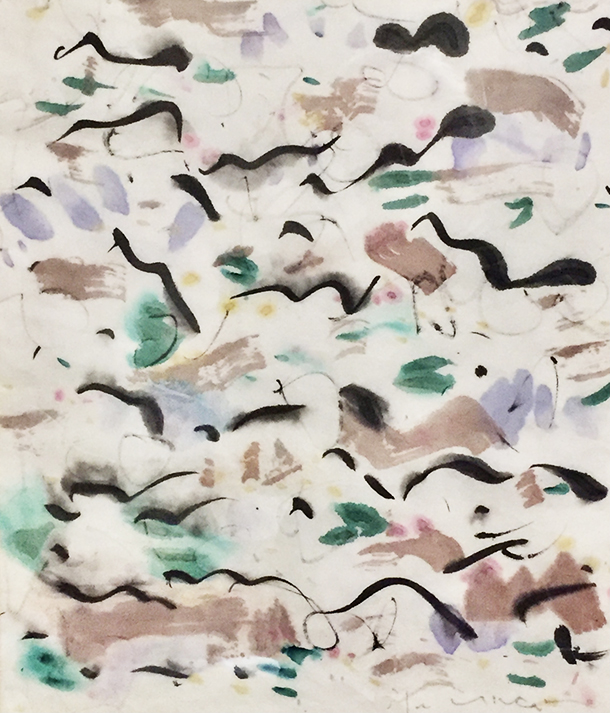

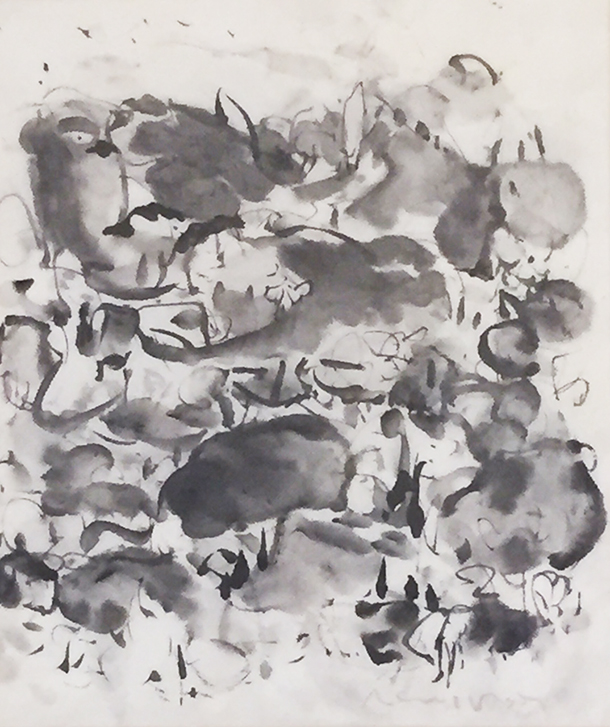

In time, his mostly monochromatic paintings, which had emulated classical Chinese and Chinese-derived Japanese styles, made way for the introduction of color, and Newman’s own strong, spirited handling of his brush emerged. In his own way, he brought together his own sense of draftsmanship, the influences from ancient East Asian visual art that he revered, and influences from modern, abstract art of the West, many of whose notable makers had also been influenced by Asian calligraphy. This combination of sources has shaped Newman’s signature art-making methods to this day.

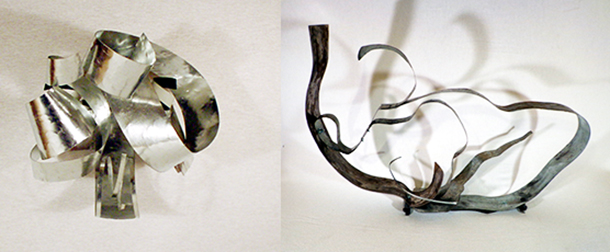

“Once I got back to Japan, after having worked in other media at the art school in San Francisco, I was back to paper,” he noted. Over the years, Newman has worked in acrylic on canvas and he has also made shaped-metal sculptures whose fluid forms recall the spirit and character of his painted brush strokes. About his favorite material, he said, “With paper, I feel the relationships of watercolor or ink and the paper working together — and with me. A leaf falls on my shoulder, and I just paint.”

Although he makes his task sound easy, in fact, like generations of skilled ink-wash artists before him, Newman knows that his painting technique requires a finely tuned understanding of such key factors as the character and quality of his paper, including its absorbency; how much ink and how much water are mixed together to create a particular shade of gray or richness of black (or how much paint saturates a brush); how thick or how liquid his ink (or paint) might be; how long it will take for a stroke of ink or paint to soak into his paper; and what the resulting luminosity or visual texture of a dried brush stroke might turn out to be.

In ink-wash painting and calligraphy on paper, time is as much an art-making material as an artist’s ink or paper.

Newman spent 18 years in Japan, mostly in Osaka, a big commercial city on the southwestern coast of the main island of the Japanese archipelago. There, he lived modestly in a one-room apartment in the city’s shitamachi, or working-class district, which was filled with small shops, public bathhouses, and narrow lanes. The head of a small manufacturing company became one of his main patrons, routinely buying paintings from Newman’s exhibitions at Galerie Petites Formes, a venue in Osaka that showed modern art. Newman told me, “It was the many influences from Japan that really sparked me to create the kind of art I make and that cemented it. All as a way to express life and to share what I was learning and experiencing.”

Newman made abstract paintings that referred to rocks, plants and landscapes, and views of mountain ranges. In them his brush danced from section to section of his pictorial space, touching down just long enough to leave shape-suggesting daubs of ink or watercolor — and often combining both — in animated compositions that felt rhythmic and musical. Over the years, Newman produced various groups of thematically or technically related paintings, such as his “Still Flowing Yet a Stream” (1989), “Partitive Light” (1991), and “Hualien Study of Light” (1994) series.

In the early 1990s, Newman fulfilled a long-held dream and spent an extended period in Paris, visiting museums, soaking up that city’s ambiance, and creating new paintings in a skylit artist’s garret straight out of la vie bohème. In Paris, he met a Taiwanese woman who would become his wife; together, they had two children and later moved to and ran a bakery in Taiwan. Later still, they settled in the Seattle area, where Newman began making his metal sculptures. In 2020, just before the outbreak of the worldwide coronavirus pandemic, Newman became an artist in residence at National Dong Hwa University. More recently, at this large public institution, he has been teaching a popular course he developed called “Art and Life.” In Taiwan, he is associated with the Taipei-based Dongli Gallery.

“A lot of my learning, observations, and ideas have gone into this course,” Newman explained, drawing parallels between what he has absorbed during his life’s journey as an artist and what he has poured into his teaching.

He added, “For me, influences from Japan have always had more to do with the space that was and is to be found everywhere in Japanese life — the space you see or find in Japanese art but also real, physical space. I’m not just referring to what is known in art as negative space or positive space. All of our actions or deeds — they’re also related to space. In my classes, I try to help my students — and myself — understand the relationships between thoughts, actions, space, and art, to understand the basic communication to be found in or through all of them.”

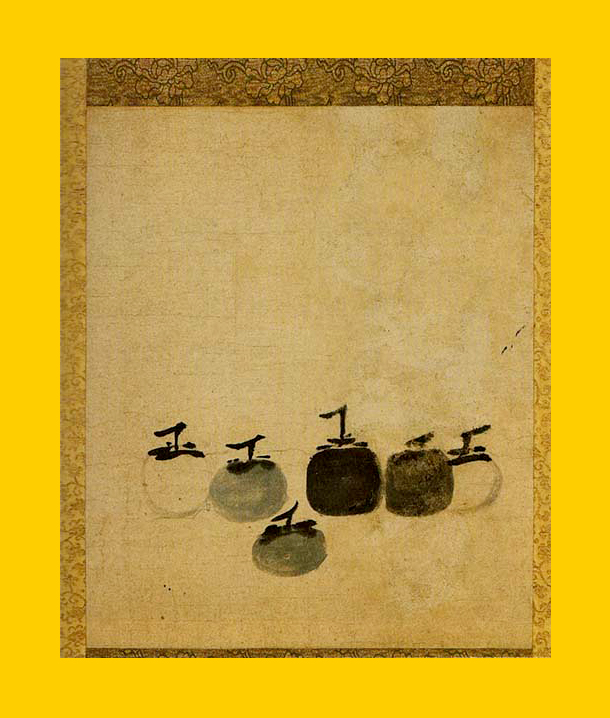

Newman called attention to the 13th-century, ink-on-paper painting “Six Persimmons” by the Chinese, Buddhist monk Muqi Fachang, which now resides at a temple in Kyoto and is very rarely displayed. Connoisseurs of ink-wash painting admire Fuqi’s picture for the contrast of its thick and thin lines, both the delicacy and the implied solidness of the fruit forms they depict, and the manner in which its subjects seem to float in their broad, deep pictorial space.

“What is it that I’ve been trying to say as an artist?” Newman asked, interrogating himself.

He replied, “I believe that Muqi expressed it best in ‘Six Persimmons.’ I was originally drawn to Asia because of the abstraction I recognized in the works I saw that had come from there. They seemed to say what was not being said; they alluded to something more than explicitly stating something. In such works, a single line can say almost everything. (That’s something you can find in the British modern artist Ben Nicholson’s line drawings, too, by the way.) Allowing the space in a picture to convey almost everything. Over the years, my travels have taken me from abstraction to Buddhism and back again to and through abstraction.”

I asked Newman if, now, as an artist who has produced a broad body of work that reflects a complex life journey, he might have any advice for younger art-makers.

True to his self-effacing style, at first he seemed reluctant to issue any grand pronouncements. Then he offered these bon mots: “Be true to yourself. If you’re not, then what have you done? What have you made? Not art. Be truthful and, as a gift to all, respect humanity. Now that is art.”

He also cited wúwéi, a Taoist concept that, as Newman put it, holds that “a continuous stream of spontaneity emerges from the rhythm of one’s circumstances.” The gist of that memo from ancient sages: Go with the flow. Tap into it. In it, find inspiration. Don’t fear its energy. Savor it. Let it be a springboard for the imagination. Create.

Finally, he cited the 13th-century Zen Buddhist priest Dōgen Zenji, who in a waka verse wrote:

Spring, flowers.

Summer, cuckoos.

Autumn, the moon.

Winter, snow does not melt.

All seasons pure and upright

As our interview concluded, the time had come to slosh a brush in a watery goo of deep, black ink, to imagine the summer light in coastal village in the south of Japan, to make a decisive mark on a fresh sheet of handmade washi, and to long for the sound of a lone, plaintive cuckoo.

Resources

Website of the artist Michael Newman; click here.

Works by the artist Michael Newman available on the Saatchi Art website; click here.

Facebook page of Dongli Gallery, Taipei, Taiwan, which currently handles Michael Newman’s work; click here.