FROM FRAMING A PICTURE TO FRAMING A QUESTION, ORGANIZING OBJECTS, INFORMATION, OR IDEAS IS — OR CAN BE — AN IMAGINATIVE, CREATIVE ACT

by Edward M. Gómez

An old, tired, worn-out-its-welcome year fades, and a new year bounces into view, fresh with promise and potential. Will this be the year that an unstoppable rash of peace, love, and understanding, fueled by a rush of goodwill and common sense, breaks out and spreads across the globe?

Even to imagine such a miracle is to begin to organize or frame certain ideas (and ideals). We humans, with our capacities for communication, creating and using tools, and solving problems, are uniquely equipped to gather and put in order both physical objects and the output of the workings of the mind.

Writers, editors, and politicians speak of “positioning” a subject to be examined or discussed; theater-production designers literally work within certain neatly defined, physical parameters to create spaces of illusion; painters work out expressive compositions within the confines of what is normally two-dimensional pictorial space; and, of course, all sorts of critical-analytical tools, systems, and devices, from Hegelian and Marxist interpretations of history to Chemistry 101’s periodic table of the elements provide intellectual frameworks for that which is often intangible, fleeting, and seemingly unknowable.

It’s all framing, and it’s the process or act of framing just about anything that is on our minds this month as we welcome the arrival of 2023. Maybe it’s because the start of a new year offers a natural kind of framing device — for the activities, adventures, and accomplishments of the next twelve months to come, as well as, retrospectively, for all that occurred in our own lives and around the world in the year that has just ended and that’s ready to be packed and stored away like so many dusty knickknacks and photo albums in an old trunk.

A tote bag we spotted not long ago bore a quote attributed to Pierre-Auguste Renoir, in which the French Impressionist pioneer supposedly observed that a most satisfying reward for any painter’s painstaking efforts to produce a good picture is a good frame to go with it.

In late 2020, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, the Swiss art historian Michel Thévoz’s book Pathologie du cadre: Quand l’art brut s’éclate (Pathology of the Frame: When Art Brut Explodes) was published, in French, by the Paris-based Éditions de Minuit. In this short, probing examination of the functions and implications of the artist’s act of framing his or her subject matter within a work of art, Thévoz looks at the frame as a compositional tool for organizing pictorial space and as a conceptual device for delineating intellectual, social, psychic, and other kinds of boundaries, especially as it has been employed by the makers of art brut.

Thévoz has written extensively about art brut. He was a friend and close collaborator of Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985), the influential French modern artist who, in the 1940s, based on his research and collecting activities in Europe, first articulated the aesthetic characteristics that typify art brut (literally, “raw art”) and gave the phenomenon its name. Thévoz became the first director of the Collection de l’Art Brut, a museum in Lausanne, Switzerland, which Dubuffet founded in the 1970s.

In Pathology of the Frame, excerpts from which we’ll be publishing here soon, in English, Thévoz observes that the French word “cadre” (frame) has various and sometimes related meanings. Among them is “context”, which recalls the word “framework” in English. The meaning of “cadre”, Thévoz points out, can be “environmental, topological, geometric, architectural, instrumental, hierarchical, educational, judicial, philosophical, aesthetic, etc.”

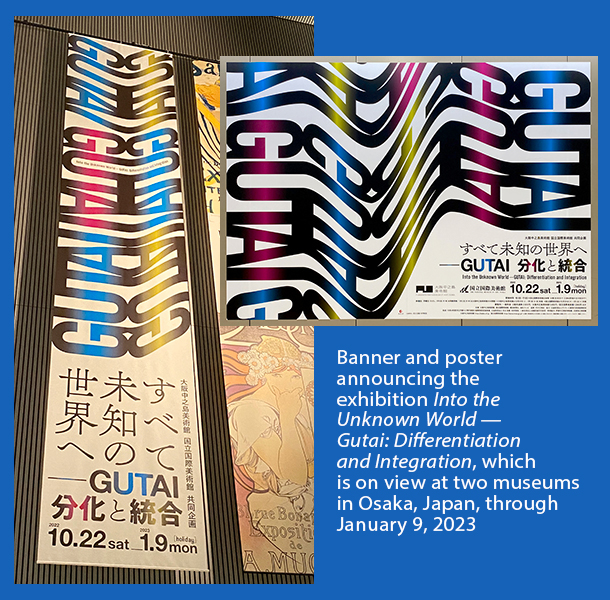

Recently, in Osaka, the large port city in southwestern Japan, I stumbled upon a most unusual work of modern art in a large exhibition chronicling the achievements of the Gutai Art Association. This large survey presentation, Into the Unknown World — Gutai: Differentiation and Integration, is being presented now, through January 9, 2023, at two venues, the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, and the National Museum of Art, Osaka.

The Gutai group was founded in Ashiya, a coastal city situated between Osaka and Kobe, in August 1954 by Jirō Yoshihara (1905-1972) and 16 younger artists who shared his interest in exploring experimental, avant-garde art forms. Yoshihara was the scion of a family whose company sold cooking oil. Although he was a businessman, he had studied art on his own and first made paintings influenced by French post-Impressionism and Japanese early modernism. In the early 1950s, Yoshihara learned about American and European abstractionists’ revolutionary new techniques for making art and embraced abstraction himself.

He commanded his young Gutai colleagues to strive to pursue “the possibilities of pure creativity.” His dictum: “We must create what has never existed before.” Published in 1956, the Gutai artists’ manifesto declared, “Gutai art imparts life to matter. Gutai art does not distort matter. In Gutai art, the human spirit and matter shake hands with each other while keeping their distance.”

Over the years, Gutai’s participating artists produced what art historians now regard as some of the most seminal, prototypical forms of performance art and participatory art, along with mixed-media installations and wildly inventive abstract paintings, drawings, and sculptures.

I’ve been researching and writing about Gutai art for many years, and I’ve been able to see in person some of the most historically important exhibitions that have been presented in recent decades of this kind of modern art. But a few weeks ago, at the big exhibition that is now on view simultaneously at two museums in Osaka, I discovered a work by the Gutai artist Saburō Murakami (1925-1966) that, until now, had been unknown to me. Murakami was one of the group’s most influential members, known for his art-action works that combined sculptural forms with performance gestures.

In Osaka, I came across his most humble — and perhaps most resonant — work ever. This was Murakami’s clever piece “Every Landscape” (1956), which consisted of little more than an empty picture frame hanging from the ceiling by a single piece of wire.

Through it, viewers could gaze across a large gallery space and both literally and conceptually frame what they saw as real or imagined scenes. A it turned out, with this simple piece, Murakami unwittingly had anticipated the audience-participation art that would flourish years later in the form of avant-garde “happenings” and the instruction-based works of the Fluxus artists. Murakami’s artwork invites viewers to use it as a tool to frame their vistas.

In effect, it also gives them permission to do so. This unassuming work of conceptual art is as radical in its implications as any of the seminal appropriating and recontextualizing gestures of Marcel Duchamp, postmodernist art’s patron saint, who more than a century ago first took everyday objects — a men’s porcelain urinal; a metal bottle-drying rack — and, simply by placing them in unexpected, art-display settings, aesthetically altered their meanings and values.

The wide-openness of Murakami’s frame-whatever-you-see gesture feels welcoming, invigorating, friendly, and, yes, definitely inviting.

In my imagination, I’m looking through Murakami’s humble rectangle right now, with all the surprises and uncertainties the passing time of a new year to come will bring out there on its other side. As subject matter for this peculiar work of art, it’s all too vast and unknowable, anxiety-provoking and unsettling, but it comes wrapped, like a piece of homemade sushi in a single persimmon leaf, in a blanket of reassuring hope.

Somehow, Murakami’s generously conceptual tool has allowed me to frame it all, neatly and, at least for now, efficiently — the unpredictable, the familiar, the unknowable, and the ineffable.