PICTURE THIS: SOMETIMES, ARTISTS STRIVE TO CAPTURE SOMETHING MORE THAN THEIR OBVIOUS SUBJECTS

This article first appeared in brutjournal‘s June 2022 issue. See part two, also in this current issue.

by Edward M. Gómez

Throughout the history of art, perhaps no subject has been more compelling than the human face.

Vases of flowers on tabletops, epic battle scenes, chubby cherubs frolicking with nymphs and deities, landscapes, slices of urban or rustic life, and abstract forms galore — artists have been depicting what they find around them or what their imaginations have conjured up ever since prehistoric cave dwellers scratched outlines of animals on their living-room walls with the ash-sticky tips of fire-burned sticks.

As for our fascination with portraits, should we blame it on Narcissus, that handsome, ancient Greek youth-god who, in a pre-Instagram age, just couldn’t get enough of his own reflection on the surface of a clear, still pond, only to die of thirst and starvation from staring too long and longingly at his own image?

Then there is the near-obsession that Edward G. Robinson, playing a psychology professor in director Fritz Lang’s 1944 film noir The Woman in the Window, seems to have for an oil painting he notices one evening in the display window of an art gallery next door to the private club where he will be dining with some friends. A portrait in an elaborate frame of an attractive young woman, the picture beguiles and bewitches him, and causes him to become the protagonist in a complex tale whose ending packs an unexpected, Through the Looking–Glass twist.

The subject of portraits and portrait-making in painting, sculpture, and countless other media and genres, is vast in its scope and long in its history, encompassing everything from awkward, medieval European depictions of long-necked Madonnas and stiff-bodied saints to Renaissance painters’ masterful exercises in verisimilitude based on their studies of anatomy and clever use of perspective techniques. All those eyes in old portraits that gaze straight out at viewers and then, uncannily, seem to continue staring right at them no matter from what angle or from what distance such observers might approach them — that eye-positioning trick is right out of every skilled portraitist’s textbook.

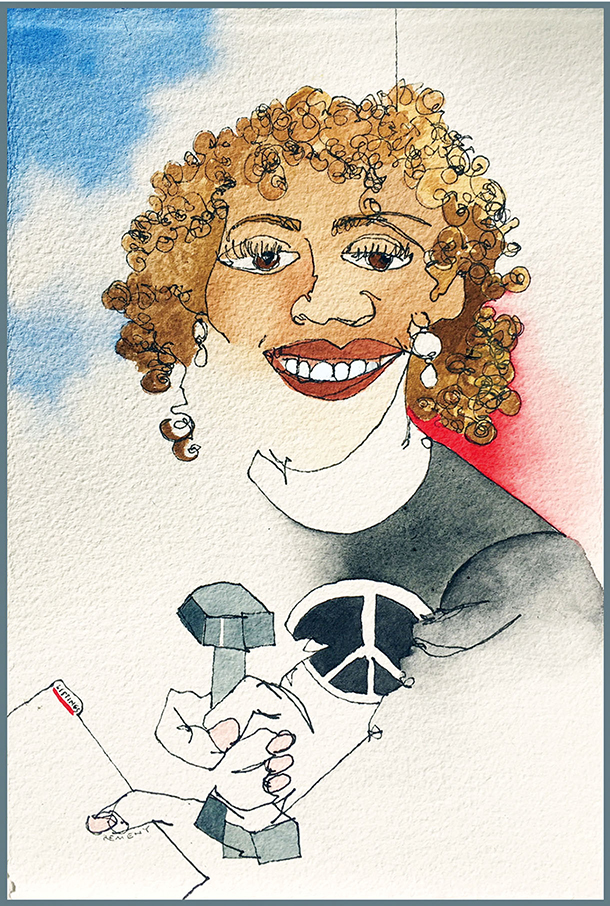

In more modern Western art, skilled draftsmen like Henri Matisse or Pablo Picasso could render faithful likenesses of their human subjects with just a few economical, knowing, well-placed lines, while a painter like John Singer Sargent could conjure up whole pageants of elegance and luxe in the incandescent brushstrokes of his pictures of high-society grandes dames and public figures, and an artist like Frida Kahlo could do Narcissus one better by creating her own images of herself — on her own aesthetic and idealizing terms — for herself and for posterity. Today, a painter like Kehinde Wiley has expended the parameters of portraiture in exciting ways with his depictions of contemporary Black men and women that dip deeply into Western art history’s canon of techniques and conventions related to the portrayal of subjects in heroic, venerable ways.

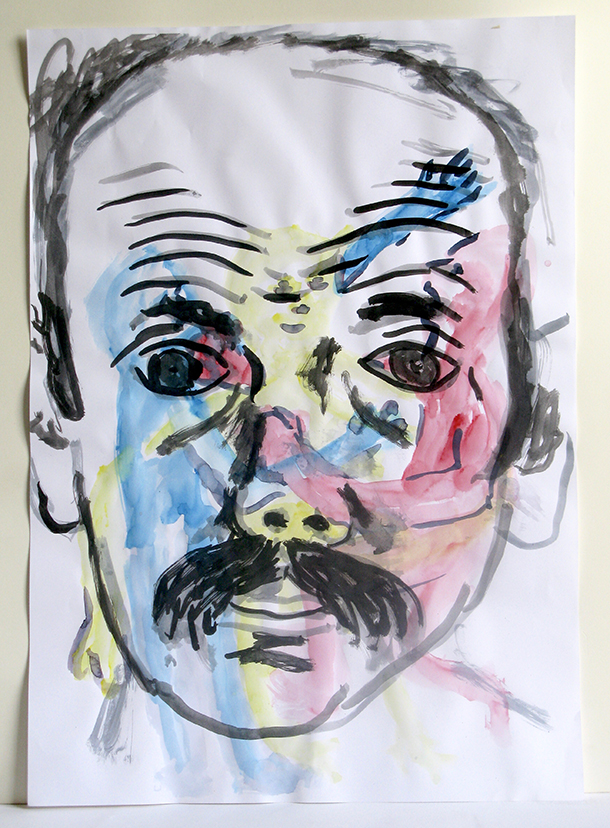

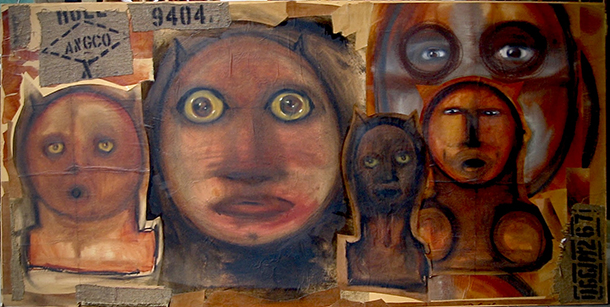

What makes portraiture something more than merely an exercise in producing images that purposefully, ideally, or hopefully resemble their subjects is the ability of the most skillful portrait-makers to capture a quality about them that is intangible but still discernible and real; call it a person’s palpable emotional-psychological or psychic energy, or his or her unique aura.

For an artist to sense and seize this ineffable force and preserve it in a work of art is no small challenge, and it is not a technical trick that can be easily taught. It is, in portrait-making, the equivalent of the “swing” that, as the old Duke Ellington standard puts it, leaves a jazz composition feeling lifeless if it is lacking and cannot be felt.

It’s this aspect of portrait-making that interests us, in particular — how artists manage to capture and convey their subjects’ invisible but inescapable vibes and how such an accomplishment enriches their work. We’re ruminating on these themes in this month’s issue of brutjournal, with a batch of articles in which artists share their observations about the pleasures and challenges of portrait-making.

(Scroll down to see a portfolio of contemporary portraits and some of their creators’ comments about them. We’ll be adding to this selection as the month unfolds.)