TAPPING INTO ANCESTRAL HISTORY AND SAVORING ART-MAKING AS MAGIC, AN ARTIST FINDS HER EXPRESSIVE VOICE

In New York City, Gray Campbell is an adjunct professor of English at Baruch College, a part of the City University of New York, and at St. John’s University. His academic writing has been published in Notes & Queries, and his dramatic work has appeared in Phantom Drift: A Journal of New Fabulism.

by Gray Campbell

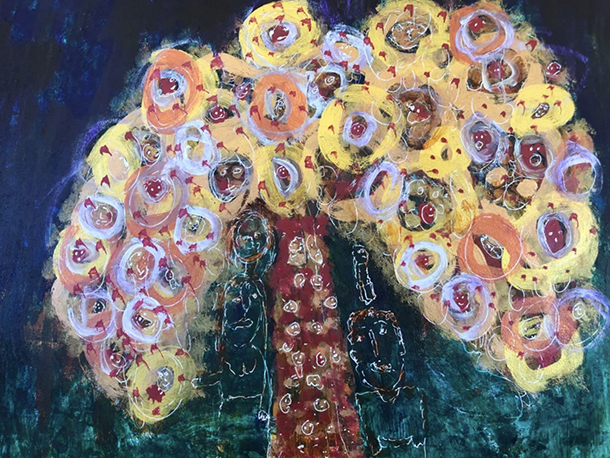

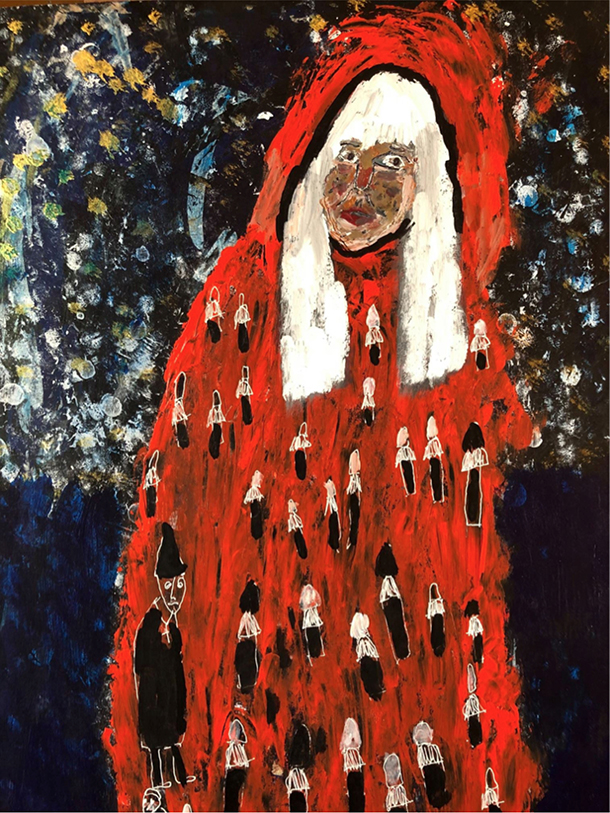

The painter and writer Reda Rackley, who goes by the artist’s name “Bonewoman” (Instagram: @outsiderartbonewoman), is a self-described outsider artist who lives in Carmel Valley, near Monterey, in east-central California. Her paintings are notable for their images of crones, witches, and female-centered spiritual communities. Now in her sixties, several years ago, Bonewoman began blossoming as an artist. She works rapidly, often finishing a painting in about 30 minutes.

Before I spoke with her for this interview, which took place in 2019 and has never been published before, the artist had not spoken in detail about her work and ideas, nor had her paintings received much attention in media outlets focusing on the activities of self-taught artists.

Colin Gray Campbell: Where does your artist’s name, “Bonewoman,” come from?

Reda Rackley (“Bonewoman”): It’s a name I gave myself. For me, the “Bonewoman” is as old as eternity — she wants to get down to the bone, down to the roots. She’s interested in the truth that lives in the depths, the darkness, the roots, and the bone marrow. It’s an archetypal energy that I embody and that I’m curious about. There are a lot of bonewomen in the world

Campbell: Are you formally, that is, academically trained as a painter?

Bonewoman: I had a horrible experience as a child. In third grade, a teacher held up a painting and said, “This is how not to paint a flower.” And for years and years, I would never even consider picking up a paintbrush or entering any kind of art room. Several years ago, I had a dream about flying through the Grand Canyon’s walls, holding a huge paintbrush. I was painting images on the Grand Canyon’s walls, and then an old woman with long, white hair came out, grabbed my paintbrush, and said, “Follow me.”

From that dream, I thought that there must be a way we can paint without the results having to look like or be anything. That’s the only training I’ve had.

Campbell: What did teaching yourself to paint do for you that art schools never could have accomplished?

Bonewoman: I don’t know that I actually have taught myself to paint. I show up to the canvas. I don’t have an agenda about what’s gonna come through; it’s all a completely intuitive process. I don’t paint the images. The images start to emerge out of the paint, and I just pull them out. So if you said to me, “Go paint a cat,” I really couldn’t paint a cat. But if I see an image, like when you at look at clouds and you see images [emerging in them] — that’s how I paint.

Campbell: Your paintings often focus on women and magic. Your subjects include the witch, the crone, the wise woman, the cunning woman. A painting like “Granny Witch” (2019), for example, depicts a benevolent witch through whose image you evoke the memory of Grace Sherwood, a 17th-century Virginia woman who was accused of witchcraft. Do you regard such women as your spiritual kin?

Bonewoman: They are my ancestors. My roots are Celtic, Irish, English, and Welsh. These women are my ancestors who were sacrificed — burned [as witches] simply for having been connected to the wisdom of Mother Nature, to that of women giving birth. Their magic was demonized and turned into something evil, so my art is my way of giving voice to these ancestors in the otherworld.

Campbell: I note that you use the term “otherworld” and that you spell it as one word in your writing.

Bonewoman: Yes. To me, it’s related to the soul speaking, to the manifesting of spirit into matter, and to giving voice to the unfathomable through my art.

Campbell: In a sense, can your depictions of witch figures also be seen as self-portraits?

Bonewoman: I think I carry on the lineage of my ancestors. Many generations back, it all went underground; it all got hidden, sanitized, and Christianized, and, you know, I’m just reclaiming something that’s already in my bones and that has been there through generations.

Campbell: In such paintings as “Witches Flying in Caves” (2019), “All HER Familiars” (2019), and “Elders of the Snake Priestess Clan” (2019), there’s a sense that your paintings not only depict rituals and spiritual realities but also that they promote a process of spiritual reclamation by women — and by witch figures, in particular. Do you use painting as a way of creating a witch-centered world?

Bonewoman: No, I don’t use painting in that way, because there are so many other dimensions to it. It’s as if you go into a cave and see all the old paintings on its walls, and when you put your hand on them, you can feel the ancestors — all of the magic that happened in the distant past in that cave. And you come back out and you empty it out. So the witch is part of it but it’s certainly not all of it.

In painting, there’s magic in the process but there’s also history. Archetypal energy. Depth psychology. Mythology. Spirituality. Religion. There are so many dimensions. I don’t think that one would just want to reduce it to one dimension.

Campbell: The crone is another prominent character in your work. In such paintings as “Wisdom of the Crone Lives in Her Bones” (2019), “Crone has the Final Word” (2019), and “Crone Woman” (2019), together with their accompanying texts, these pictures suggest your personal identification with the crone.

Bonewoman: Again, the crone represents an archetypal energy. You have the trinity: the maiden, the mother, the crone. Our culture has idealized the maiden, the virgin-mother, but there you have it again: the witch has been connected to death. The crone, the old one, the ancient one — she’s connected with death, but we have not wanted to look at death and dying, at the old face, the body that’s going back to the earth. For me, though, this is about reclaiming; as I am a crone now myself and stepping fully into that role, this is a way for me to reclaim the wisdom I get to pass on to my daughter and my granddaughter. It’s an honoring of that wise-woman, elder’s wisdom.

Campbell: You often write prose texts to accompany your paintings, placing them alongside reproductions of your work when they appear online. Part of the text you wrote for the painting “Wisdom of the Crone Lives in Her Bones” says:

“I bow at the feet of the old crones that will look at you with the eye of death and say, ‘Time for the children to grow up. Time for the little boys that call themselves men to grow up! Time for the women that keep playing by the rules of big daddy to grow up! Time to stop looking outside yourself for someone to save you!’”

Bonewoman: Through those texts I can give voice to what I feel in my bones needs to be looked at and not turned away from — to be looked at in the shadow of what’s going on in our culture, in the shadow of the masculine and the feminine. That’s who the crone is. She doesn’t turn away from death, or destruction, or what is ugly.

Campbell: Do you use painting as a means of communing with the dead? Can you talk about the relationship between painting and your contact with the “otherworld”?

Bonewoman: I’m blessed to have been able to study with Malidoma Some, an African elder from Burkina Faso. I started in 1998 with the aim of becoming an initiated diviner, reading the patterns of stones, bones, cowrie shells, and other objects, and then to performing healing rituals. Malidoma Some assisted me in returning to the wisdom my Celtic ancestors, who were midwives, granny witches, diviners, soothsayers, and seers. I feel the breath of my ancestors come dancing through the paintbrush when I enter my studio and step into the “otherworld.”

I asked Malidoma Some, “Why would I want to recall ancestors who left quite a painful legacy?”

He replied: “You do it for the next generation so that they won’t have to carry the sorrows of the dead.”

Campbell: Some outsider artists are marginalized individuals who find themselves on the fringes of mainstream society. Some are even social outcasts. You, however, appear to live an intensely healthy family life centered around women in a kinship group. How do family bonds between multiple generations of women influence your work?

Bonewoman: I grew up around a lot of women — I had four sisters. My mother died when I was fifteen. That sent me off on a pilgrimage; I left the Deep South and made my way to California, where I knew no one and had no family relations. In order to survive, I had to develop relationships with other women, which mostly came from my being a poor, single mom and having a child.

I began to gather women who needed child care and help, forming a women’s group that still gathers every month, after 32 years. We still support, encourage, celebrate, grieve with, and love each other after all these years. I would not be who I am without this group of women.

My art gives voice to all the women through many generations who, still today, cannot speak, paint, write, or dance their truths for fear of violent retribution or even death. I think of all the women artists and creative women who ended up in mental institutions, some of whom took their own lives, because they were not free to express their deepest souls or had to become muses for the male gaze and not receive recognition for their own creativity.

Campbell: To what extent is your painting the product of planning? Or to what extent do you rely on chance or risk-taking?

Bonewoman: There’s no planning. The only thing I plan, I suppose, is my commitment to showing up and making time and space in which to paint. It’s one of my meditations, a practice by which to take good care of myself and my psyche.

We live in turbulent times.

It’s self-care for me.

Resources

The artist Bonewoman’s Facebook page can be found here.

Her personal website can be found here.

Some of Bonewoman’s artworks can be seen on this website.