AN EXHIBITION IN SWITZERLAND EXAMINED THE NATURE — AND THE JOY — OF CHANGE

by Edward M. Gómez

For those who find illumination and maybe also guidance in aphorisms and fortune-cookie wisdom, that old French chestnut, “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” (“The more things change, the more they stay the same”), describes a supposedly unshakable truth about reality, one that, implicitly, is or should be somewhat obvious, too. Except, of course, when it finds itself bucking up against a revolution.

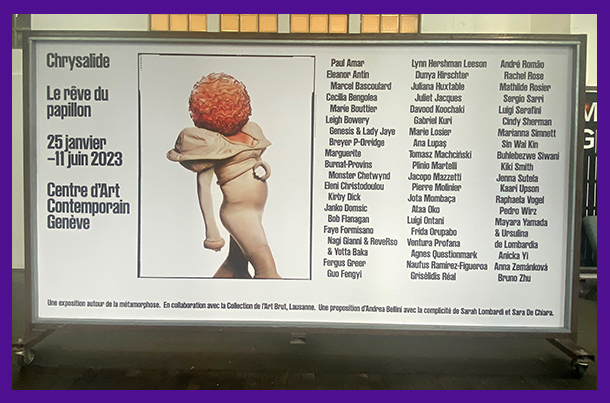

Such a spirit of change — gradual and subtle, or rapid and forceful, and, often, deeply personal and determined — served as the central theme of Chrysalide: le rêve du papillon (Chrysalis: The Butterfly Dream), one of this year’s most intriguing contemporary-art exhibitions. It was presented from January 25 through June 11, 2023, at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, a venue in Geneva, in southwestern Switzerland, that is one of that central-European country’s high-profile showcases for cutting-edge and experimental art forms. Geneva is well known as a very international city; it’s the home of numerous United Nations agencies and of CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research), an intergovernmental organization that operates the world’s largest particle physics laboratory.

Just as the scientists at CERN are known for their focus on the character and behavior of subatomic particles, the artists whose works were featured in Chrysalide could be seen as investigators of the depths of the psyche, a region in which unknowable forces help shape one’s sense of self.

Now, several months after the exhibition closed, its richly informative, well-illustrated catalogue, which, in its imaginative and analytical reach, goes beyond the material and ideas that were showcased in the physical exhibition, has been published. It is available for purchase from the website of the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève in separate French– and English-language versions.

Both the exhibition and its accompanying book called or call attention to the manners in which artists may think about their identities, either as they regard and appreciate them in deeply personal ways or as they might wish for such identities to be recognized in and by society — that is, by the wider world beyond the self.

Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève director Andrea Bellini, who served as the exhibition’s curator and the book’s main editor, pointed out to me when I visited the big show in person toward the end of its run that, perhaps more than the usual exhibition-plus-catalogue combination, Chrysalide: le rêve du papillon and its accompanying book together may be seen as a more holistic research project and philosophical-psychological exploration of certain artworks and the ideas and emotions that motivated their creators to produce them. (Bellini organized the exhibition with collaborative contributions from Sarah Lombardi, the director of the Collection de l’Art Brut, a museum in Lausanne, Switzerland, and from Sara de Chiara, his curatorial colleague at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève.)

Bellini observed, “Many of the works in this exhibition refer to transformation in a general sense and also, as in the works of such artists as Marcel Bascoulard, Leigh Bowery, Luigi Ontani, and Genesis P-Orridge, to a desire for personal change, which sometimes can be quite dramatic. Some of the works on view suggest or remind us that both personal change — the transformation of the appearance or other aspects of an individual — and broader social change are forces that are always in motion.”

Chrysalide featured numerous images — on paper and other surfaces, including, as captured in photographs, the human body itself — depicting the human form decorated with makeup, tattoos, or costumes, or otherwise embellished and visibly transformed.

On view, for example, were Fergus Greer’s color photographs from 1990 that caught the Australian-born performance artist Leigh Bowery (1961-1994) posing in a cloche hat and bands or swaths of colorful fabric. In these pictures, Bowery, who was a big, corpulent man, exposes ample amounts of his fleshy body, which he often made a focal point of his provocative performances. Bowery’s flamboyant, transgressive aesthetic emerged against the backdrop of England’s New Romantic movement in music and fashion of the 1980s and strongly influenced it, too.

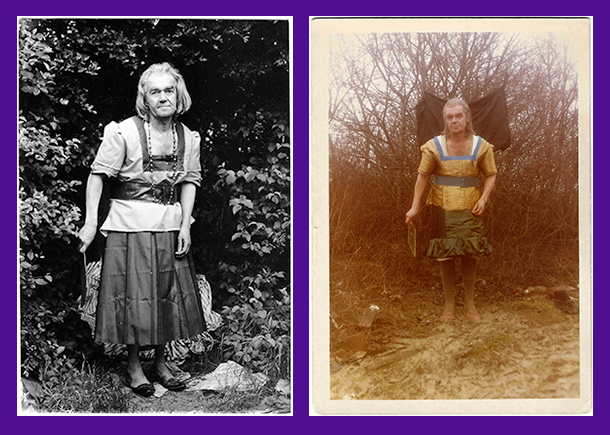

Similarly, what is now known as gender-bending or subverting the familiar trappings of conventional gender roles was the signature aspect of the performative costuming-as-art activity of Marcel Bascoulard, who lived in Bourges, in central France, where his mother had been institutionalized after killing her husband.

Bascoulard, who lived in an abandoned house, produced drawings (of women in everyday dresses or of the old part of Bourges), photographs, and poetry. In private and, boldly, sometimes in public, too, he wore women’s clothing, because, as he once noted in a letter, “I think it’s more aesthetically pleasing.” He added, “In terms of the needs of art, when I put on female attire, I take my camera with me and I have people I know take pictures of me.”

Chrysalide also featured the work of Tomasz Machiński (1942-2002), a Polish, self-taught photographer and performer who produced more than 22,000 photo self-portraits in which, as Sara de Chiara writes in the exhibition’s catalogue, he “appears variously in the guise of figures from history, literature, and politics, as well as stars of the silver screen and pop-culture icons, straddling all ethnic, genre and social divisions.”

As de Chiara explains, Machciński, who became an orphan during World War II, began creating his vast photo-portrait series after receiving “the autograph card of the Hollywood actress Joan Tompkins bearing the message ‘With love to “Tommy” from “Mother” Joan.’” That message, which Tompkins had sent out “as part of a remote adoption program, gave rise to a misunderstanding and launched [Machciński’s] work investigating the polymorphic identity of the artist.”

In various sculptural objects, artists also evoked the notion of change or, more dramatically, of physical transmogrification. Consider, for example, some of the works of the Italian painter, sculptor, and maker of drawings Luigi Ontani, who was born in 1943 and today lives and works in Rome.

Ontani came on the Italian contemporary-art scene in the 1960s, by which time conceptual art and homegrown arte povera had become influential forces. However, Ontani chose to look back at and rework imagery from older, classical art forms, exploring his ideas in performance, photography, and the making of tableaux vivants. Like the contemporary Japanese artist Yasumasa Morimura (born 1951), who, to make his vivid photo works, routinely dresses up to resemble well-known pop-culture figures or art-historical subjects, Ontani made a series of photos in which he appeared in the guise of such cultural, historical, or mythical figures as Dante Alighieri, Pinocchio, Christopher Columbus, St. Sebastian, and Bacchus. Ontani also depicted some of his own features in mysterious masks and sculptures representing imaginary deities, animals, or historical figures.

Bellini noted, “In some of their works, these artists seem to suggest that, for them, there is a spiritual dimension to the kinds of personal transformation in which they’re interested and that they represent.”

Such multifaceted change is inescapable in the artistic undertakings of the late Genesis P-Orridge, who was born Neil Andrew Megson in Manchester, England, in 1950, and died in New York in 2020. In fact, radical physical transformation was the hallmark of P-Orridge’s entire artistic career, which Bellini finds especially fascinating; he met and got to know the artist when, years ago, prior to becoming the Swiss art center’s director, he lived and worked in New York.

For Megson/P-Orridge, life and art were indelibly entwined. Emerging in the late 1960s from avant-garde activity in music and performance art that challenged social norms with its handling of sex-, pornography-, and occult-related themes, P-Orridge later became a founding member of Throbbing Gristle, a band that pioneered the abrasive sound of so-called industrial music; in the 1980s, P-Orridge founded the band Psychic TV.

Then, in the 1990s, the artist-musician left England and moved to the United States. There, P-Orridge met Jacqueline Breyer, who would later become known as “Lady Jaye.” The two were married in

1995 and then, as de Chiara recalls in the Chrysalide catalogue, went on to create “their most radical and visionary project, which blurred the boundaries between artistic performance and existential experience, as well as between the two sexes and between art and biology.” P-Orridge and Lady Jaye “endeavor[ed] to fuse themselves into a single new entity: the pandrogyne[,]” in a “long-term project during which the couple underwent numerous plastic surgeries with the aim of resembling each other more closely and generating a single, new being called ‘Breyer P-Orridge.’”

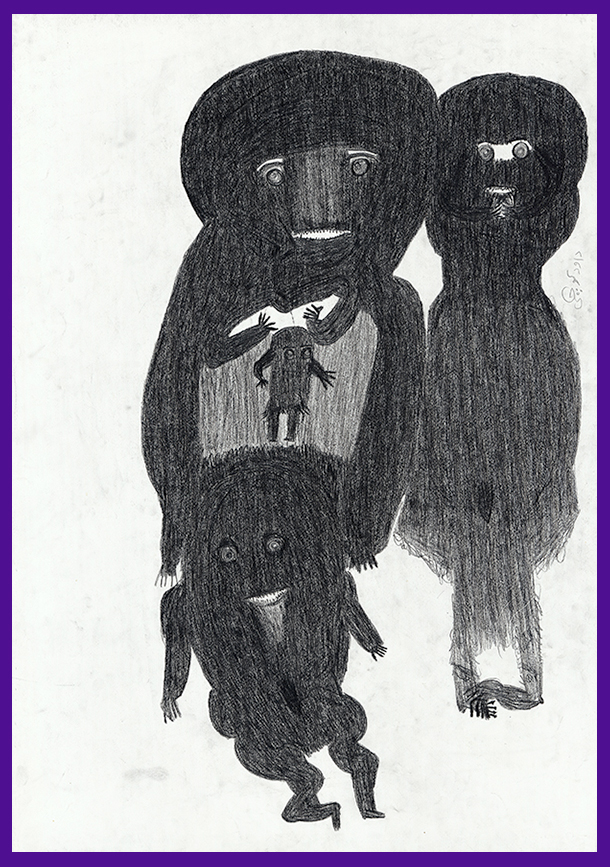

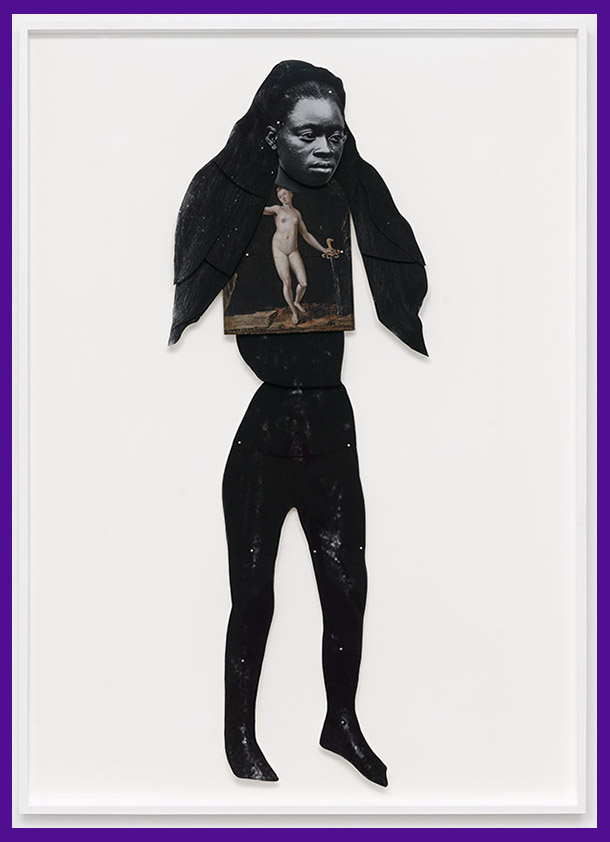

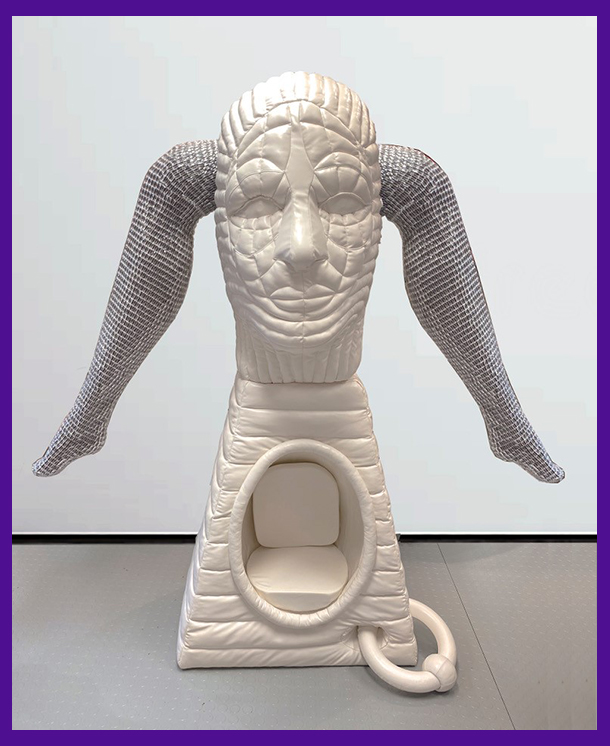

Elsewhere in Chrysalide, the theme of transformation — physical or spiritual-psychic, tangible or imaginary — finds expression in such works as the Iranian self-taught artist Davood Koochaki’s pencil-on-paper drawings of strange, shaggy characters out of whose lumbering forms similar, new figures seem ready to emerge; in the photo-collages of the Norwegian artist Frida Orupabo (born 1986), which reconsider stereotypical representations of Black people; and in the mixed-media, padded-fabric sculptures of the Greek artist Eleni Christodoulou (born 1965), which evoke a sense of the human form’s vulnerability with their protruding legs and embedded body parts.

Given that so many of the artists whose works appeared in the exhibition examined or reflected the theme of self-transformation through the search for and constructing of desired identities, in the Chrysalide catalogue, Bellini, borrowing a phrase from the contemporary Spanish writer and curator Paul B. Preciado (who was born Beatriz Preciado in 1970), refers to these art-makers collectively as “souls in exile.”

For each of them, their art seems to say, life is or can or maybe should be in flux, a notion that is strongly echoed in Buddhist thought, which holds that nothing is permanent, and that the only certain aspect of “reality” is its perpetual impermanence.

In his introductory essay in the book, Bellini proposes that, even as we humans try to grasp and keep up with broader currents of change in our respective societies and in the wider world around us, we should not “[be] afraid to change ourselves.”

Taking a cue from the diverse selection of artworks he and his curatorial team assembled for the Chrysalide exhibition, Bellini further suggests that, for any individual who is alert, creative, and perhaps courageous enough to undertake some kind of personal transformation, the journey from chrysalis stage to butterfly beauty could be quite meaningful — and rewarding.

It may turn out, he observes, to be a “poetic, imaginative, and political adventure, a meditation on life as movement, a rejection of every type of categorization, a form of contact with the depth of one’s being, and an exploration of one’s own non-biological identity.”

Perhaps the more things change, the more they may deserve to change — or more actively and purposefully, to be changed — some more.

to read the whole article.