MORE THAN A WAY OF MAKING ART, FOR MANY CREATIVE TYPES, IT’S A WAY OF LOOKING AT THE WORLD

by Edward M. Gómez

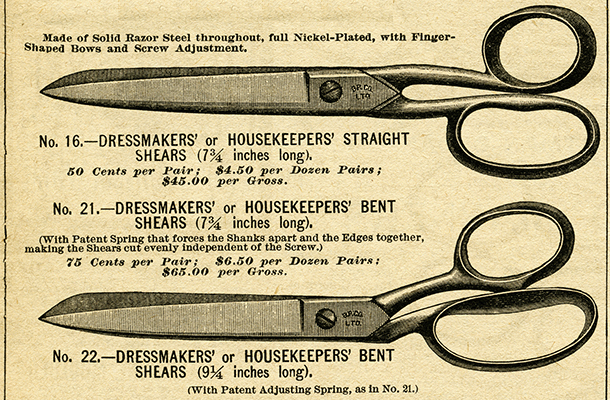

We know that many an artist has a lively sense of humor and can be quite a cutup but what interests us this month is how — and why — so many art-makers like to routinely pull out their shears and glue pots, cut up all sorts of paper and cardboard, and gather up other materials, too — scraps of fabric, pieces of string, tiny stones, bottle caps, and more — and then affix their myriad, disparate treasures to a support surface in combinations that can sometimes turn out to be as baffling as they are compelling, elegant, strikingly decorative, or rich in implied, overlapping meanings and messages.

Of course, when it comes to the history of modern art, the techniques, aesthetics, and creative points of view associated with collage have been evolving for more than a century. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque famously experimented with collage as they developed Cubism’s working methods and guiding principles in the early 1910s, in effect inventing the genre, in which they brought together materials from the real world, such as scraps of newspaper, wallpaper, or rope with paint and drawing.

Collage (from the French verb “coller,” meaning “to glue” or “to stick”) is related to assemblage, which tends to refer to the combining of assorted materials or objects to construct a form. Through both of these modes of combining sometimes unexpected, unusual, or found materials to create new shapes or new, multifaceted objects, an artist’s resulting effort may refer to those of its constituent parts even as its appearance or composition might suggest all-new, unanticipated meanings.

Other early modernists seized upon Picasso and Braque’s invention and further developed it for their own expressive purposes. The Futurists, the Dadaists, and legions of other avant-gardists, graphic designers, and filmmakers found endless creative license in collage’s practice of bringing together and juxtaposing imagery and materials whose meanings and values became altered through the process of being imaginatively and sometimes radically combined.

We checked in with the performance and multi-media artist Martha Wilson, the founder and now director emerita of New York’s Franklin Furnace Archive, a former downtown-Manhattan arts venue that is now an online repository of a wealth of material documenting the history of the avant-garde over the past half-century. As much as strong conceptual-art currents can still be felt coursing through much of what artists (at least many academically trained ones, that is) are producing today, what is collage’s lasting impact, we wondered.

Wilson observed, “The collage-maker I admire the most is the German Dada artist Hannah Hoch [1889-1978], who used regular stuff to great artistic ends; some of her work was politically charged, and the Nazis prohibited her from exhibiting her art. Nowadays, I’d say that there is a continuum from painting through collage to sculpture, with artists incorporating everything into their work, from the broken plates in Julian Schnabel’s paintings to the straightened rebar lying on the floor as sculpture in Ai Wei Wei’s powerful work concerning the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Since, today, in the postmodern era, any material under the sun is fair game, it’s all the stuff of collage!”

In fact, Wilson’s comments serve as a reminder that, as much as certain aspects of doctrinaire postmodernist critical theory tend to take aim at some of the central assumptions or themes of modernism and at certain historical features of modern art’s canonical history (such as, for example, its emphasis on and exaltation of the heroic, individual artist-creator), nothing could be more postmodernist in spirit or outlook than the approach to gathering, appropriating, repurposing and, to use a favorite pomo jargon word, “recontextualizing” source materials than the practice and methods of collage.

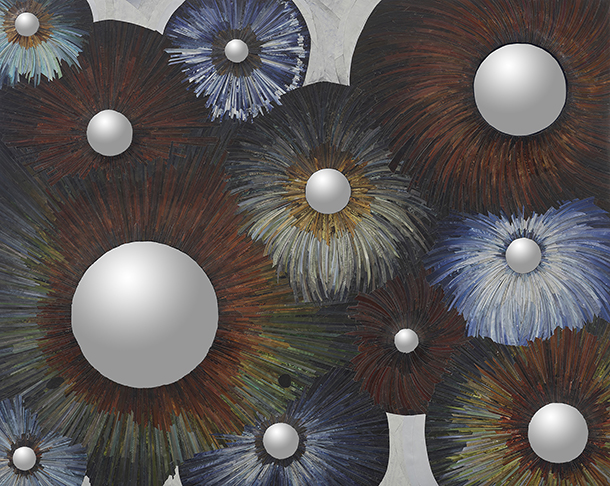

In this issue, we present portfolios of works by a wide variety of artists who are making powerfully expressive, technically inventive collage works or who are incorporating elements of collage into their work in other media and genres.

This issue launches with a first batch of articles about such art-makers, and as the month of May unfolds, more features will roll out each day looking at several more.

After getting to know the work of these imaginative artists, who recognize no limits when it comes to what they’re willing — or tempted — to bring together and mix up and mash up in provocative ways in compositions packed with resonant, if not always clear-cut, meanings and messages, you might want to cut and run — right over to your own desk or studio to pick up a pair of scissors, some old magazines and paper scraps, a glue stick or bottle of glue, and some paper or cardboard to support your handiwork.

Is it true that the first cut is always the deepest — or the most exciting?