A NEW BOOK CAPTURES THE SPIRIT OF AN ARTIST WHOSE PRODUCTION LINE, LIKE HIS IMAGINATION, NEVER STOPS

by Edward M. Gómez

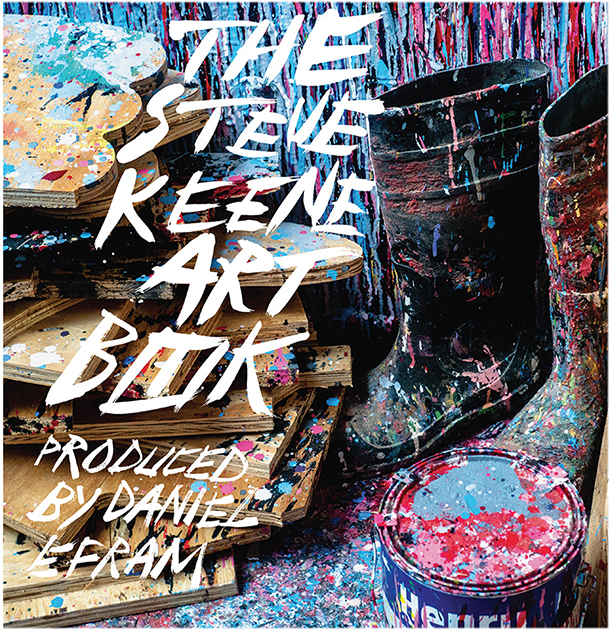

The Steve Keene Art Book

by Daniel Efram, with contributions by Karen Loew, Elle Chang, Sam Brumbaugh, Shepard Fairey, Hilarie Sidney, Christina Zafiris, and others

published by Hat & Beard Press/Tractor Beam, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-955125-14-7

Is Steve Keene the most prolific artist working anywhere in the world today? Is he the most prolific painter ever?

Whatever the most accurate statistics might indicate regarding the exact quantity of works the New York-based artist has produced to date — his own website says he has sold or given away more than 300,000 — one of the points this new book makes exuberantly clear is that Keene is a one-man art-making mega-machine on steroids.

“Have brush and colors, will paint” seems to be his motto; to say that Keene churns out his art would be churlish and unfair, especially considering how well numerous better-known, less talented art-makers on the international scene today have done for themselves merely by farming their high-priced merchandise out to fabricators to be produced for them.

Keene likes to make art — and to make it quickly and in great quantity.

His website is a straightforward, no-nonsense commercial affair. On it there is no menu linking to separate pages offering information about his background, or photos of his creations, or, thankfully, any kind of dread, jargon-filled or stilted artist’s statement.

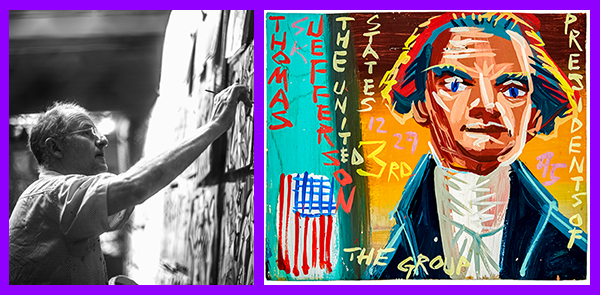

The Steve Keene Art Book has been assembled by the photographer and events producer Daniel Efram, a friend and longtime admirer of Keene’s who spent six years gathering material from art collectors and other sources to create a first-ever, comprehensive survey of the artist’s career. Prior to becoming a photographer, Efram spent several decades in the music business managing bands and planning or producing concert tours and live events.

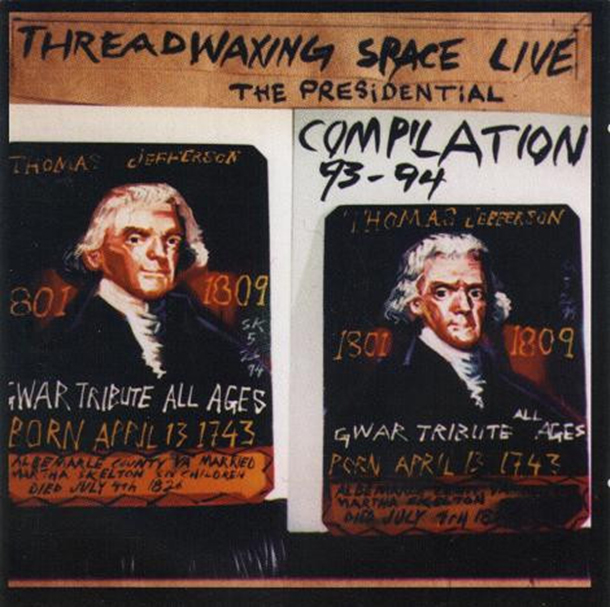

In the book, Efram recalls his first encounters with Keene’s art. In the early 1990s, he was working for Zero Hour, a record company that issued Thread Waxing Space Live: The Presidential Compilation 1993–1994, an album whose cover art, featuring portraits of Thomas Jefferson, was created by Steve Keene. The album included recordings of performances that had taken place at Thread Waxing Space, a gallery and performance venue in New York that opened in 1991 and closed a decade later.

In its early years, Efram writes in the new book, Thread Waxing Space “was regularly packed with Keene’s bright, inexpensive paintings, and everyone bought one — or five.” Over the years since then, Efram frequently commissioned Keene to produce original art for the covers of record albums made by the bands with which he was associated; he also curated two exhibitions of the painter’s works.

As Efram sees it, Keene’s approach to making art and his aesthetic outlook exemplify a do-it-yourself ethos that also characterized the 1990s music scene. “His democratic approach to making and selling [his paintings] allowed me and many of my friends to buy original artwork for the first time,” Efram explains.

He adds, “His work was informed by our scene and fit in perfectly with the attitude of the time. […] Keene’s artwork is as much about process as it is about his eccentric delivery experience. From his immersive art shows — which often include a live performance of his painting technique — to his choice-averse online ordering options (he currently sells six random pieces [to U.S.A.-based buyers] for $70.00, including shipping), Keene’s art is accessible to most” prospective customers].

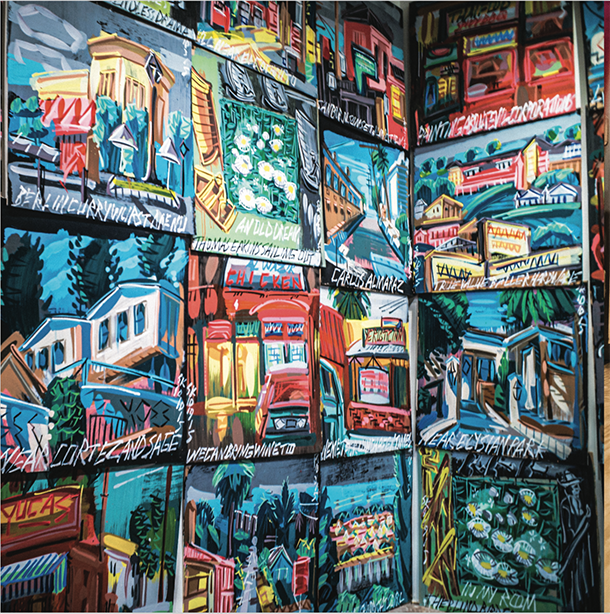

Subliminal Projects, an alternative-space gallery that was founded by the artist Shepard Fairey and the skateboarder Blaize Blouin (1968-1999) and is now located in the Echo Park district of Los Angeles, mounted an exhibition of Keene’s work in 2016. In the new book, Efram notes that, in order to produce a catalog to accompany that show, the gallery asked the artist to provide photos of the paintings he would be exhibiting.

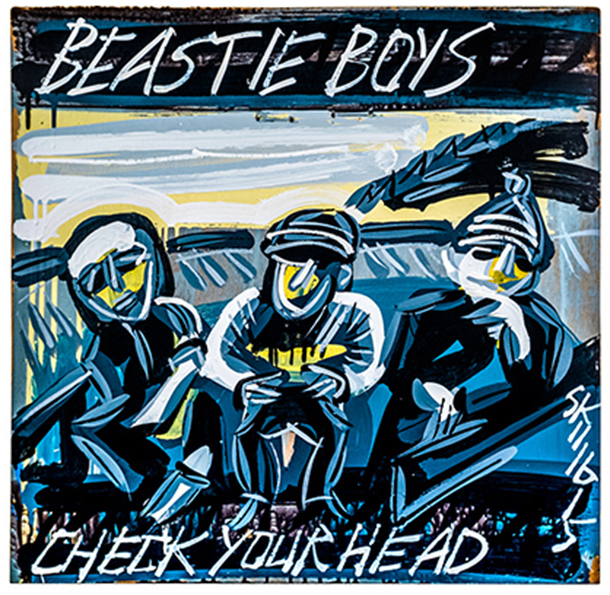

However, his work had never been photographically documented before, so, in retrospect, Efram explains, the need to prepare the requested photos served as a catalyst for what would eventually become The Steve Keene Art Book. Still, even though it features reproductions of hundreds of Keene’s creations — his boldly colored, always neatly composed paintings on plywood and other surfaces of break dancers, rock-album covers, the Coney Island Ferris wheel, New York’s now-gone World Trade Center skyscrapers, and dead American presidents — it’s daunting to think about how much of the artist’s abundant, unstoppable output has been left out.

In the new book, in a recollection of her years as a student at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, the New York-based journalist Karen Loew remembers buying some of Keene’s early paintings for just a few dollars each at a local record store and also hearing the artist and his wife on the school’s radio station, WTJU.

Loew writes, “Keene and his wife, Starling, regaled listeners with their personalized mix of rock, punk, and metal. Both grew up in Virginia — she in Richmond, he in McLean — and met in Richmond, working at the restaurant Bogart’s, while [Steve] was an art student at Virginia Commonwealth University. He graduated in 1982, married Star in 1983, and received a master’s degree in printmaking from Yale in 1984. Then the couple moved to Charlottesville so that Star could get a master’s degree in architecture; she went on to teach at the School of Architecture. Their friends in town included university student musicians David Berman, later of the Silver Jews, and Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich, later of Pavement, as well as Silver Jews.”

Of that period in Charlottesville a few decades ago, before Keene relocated to Brooklyn, Loew recalls, “With students and townies alike scooping up his pictures for $2 or $5, [his] paintings soon speckled central Virginia.” Keene told her, “I was sort of bleeding, melting into the landscape, I felt. […] I was obsessed with leaving a mark, leaving a trace of me.”

In 1997, in a display window of the Goldie Paley Gallery at the Moore College of Art and Design in Philadelphia, Keene spent several weeks mass-producing paintings in a manner that allowed passers-by to watch him work. A TIME magazine report about that event noted, “With postcards or newspaper photos as models, [Keene] uses assembly-line techniques, setting up 32 paintings and going down the line with the same brush stroke, acrylic on plywood, repeating the cycle until he has nearly identical scenes.”

That very public performance, TIME added, prompted some of the school’s professors to dismiss Keene’s creations as “schlock” or as “trivial” efforts. Their prices at the time: three dollars each. But Elsa Longhauser, the Goldie Paley Gallery’s director at that time (whose passionate promotion of the work of outsider and other self-taught artists was a hallmark of her long career) remarked that she regarded Keene as “the Johnny Appleseed of art.”

Over the years, having sold his paintings at music venues and rock concerts, directly connecting with a wide, diverse public and bypassing the traditional gallery system — and its prejudices and machinations — Keene has developed a devoted collectorship on his own terms, while moving mountains of merch. On the occasion of an exhibition of his work in 2014 at the Brooklyn Public Library’s Central Library, Keene told the Wall Street Journal that he made a point of keeping his paintings’ prices low “so that people would buy them, and I wouldn’t have to take them back home.”

In The Steve Keene Art Book, Sam Brumbaugh, a writer and music producer who worked at Thread Waxing Space in the 1990s, remembers the artist’s presentations of his paintings at that downtown-Manhattan, alt-scene venue. Brumbaugh recalls, “[Steve] was careful not to become a gallery artist and grew his audience because he stuck to his system. This isn’t to say he refused to change. The Thread Waxing crowds kept coming, and he greatly increased his production to meet the demand, fast-walked his style with intentionally hurried images and an increased brevity of phrasing.”

Keene demonstrated a real work ethic, Brumbaugh notes, adding, “Work was everything. For all the loose dash of brushstroke, he was so disciplined. And he could be severe. He had a strict Germanic streak regarding lifestyle. He lived with his wife, Star, in a loft that looked entirely like a workplace. The first time I went over for dinner, we sat on a couple of steps that led up to nothing but the only window. There was a single, hard, wood chair, and dinner was a couple of big bags of potato chips and some beer.”

Still, Keene’s art was and remains shot through with exuberance, or so it feels, but that does not mean that it is lightweight.

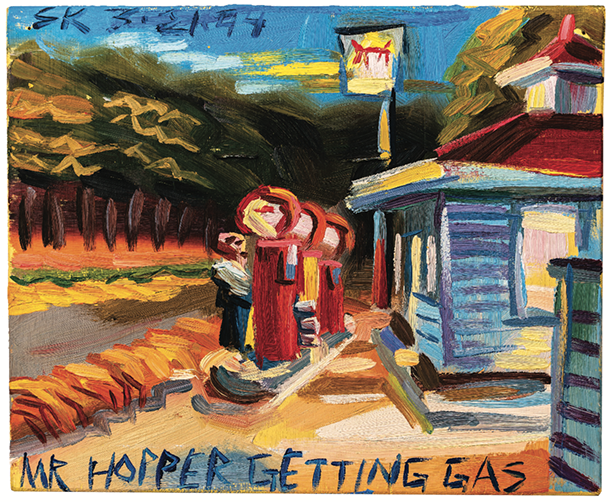

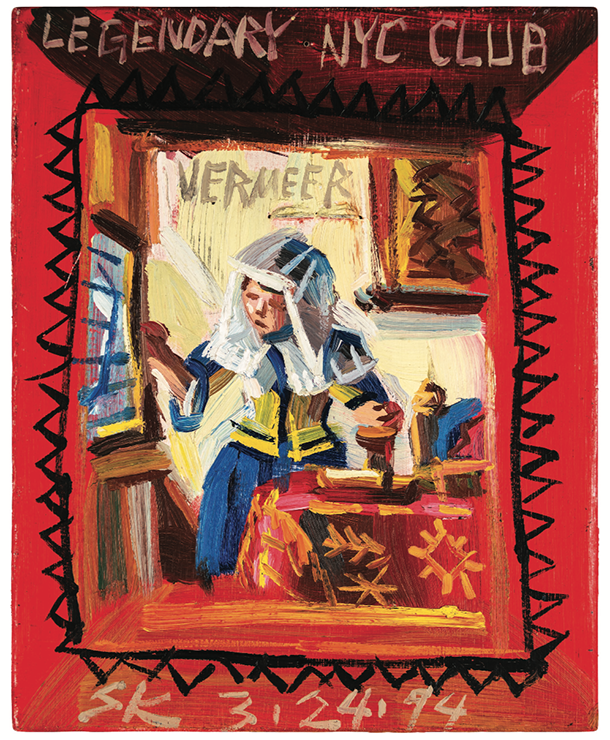

Keene can pack a send-up that is at once clever and respectful into a single small painting, such as “Mr. Hopper Getting Gas” (1994), his homage to that great conjurer of existential airs, or evoke all that’s sublime — and overexposed — in an Old Master like Vermeer (“Legendary NYC Club Vermeer,” 1994) in a picture whose simple, perfectly harmonized palette and economical brush strokes both capture the spirit of its source material and send it off on new waves of art-historical, pop-cultural, and intellectual allusions and energy.

Keene’s art is a celebration of paint as delicious liquid goo and of its powerful expressive potential; it’s an endless love song to paint as a magical medium in which color is king, and in whose handling an artist is limited only by his or her hesitation to slap it around and give it a good thrashing.

In the new book, in an interview with the artist Ryan McGinness that was conducted during the recent pandemic period, Keene says, “I know sometimes my pictures are, like, a little goofy. But what’s the difference between a thousand goofy pictures and a thousand intersecting lines? I think it does the same job.”

Keene also observes that, thanks to his mass-production method and his direct-to-the-buyer, low-cost sales system, his art “bleeds” out into the world. He says, “It’s part of the landscape. Every week I send out about 200 paintings. The feeling is that it just falls out of me.”

If he is prolific, it may well be because he has to be. Creating his art, he notes, is “really about the performance, and the fun of it is that it has become this populist community thing. Everybody grabs some paintings. That’s the biggest turn-on.”