A CONTEMPORARY BRITISH ARTIST’S ALTER EGO HAS CREATED A FASCINATING BODY OF WORK, RICH IN HISTORICAL ALLUSIONS — AND HUMOR

by Edward M. Gómez

Robert Holcombe is one of the most imaginative, original artists you will never meet.

That’s not because he mysteriously vanished, never to be heard from again, or because he died or is residing somewhere in well-maintained seclusion, doing his best to keep the intrusions and irritations of the world far from his door.

The fact is that “Robert Holcombe” does not exist. He is the invention of the British artist Wayne Burrows, who today lives in Nottingham, in the Midlands region of central England. As an artist, Burrows/Holcombe is primarily self-taught. Burrows, whose formal education ended when he was a teenager, recently told brutjournal: “I never studied art beyond secondary school and I left [school] at [the age of] 17.” He went on to work in what he referred to as “craft and print galleries, and picture-framing shops,” pointing out that, to the extent that he ever studied art-making or art history, his learning “was always informal and under my own direction, which rarely coincided with standard canons or readings.”

Burrows recalled, “Later, I worked mainly as a writer, editor, and journalist; writing about visual art, film, animation, books, music, and performance were all parts of my various day jobs, so while I never formally studied art, beyond just pursuing my own peculiar interests, I was always kind of surrounded by art and artists of various kinds.”

When and how did Burrows — or, uh, Holcombe, that is — begin developing an interest in collage and producing collage works of his own?

Burrows said, “I played around with imitating Max Ernst’s collages, sticking all kinds of weird stuff onto paintings at school in Wales — anything from bird skeletons and cowrie shells to broken circuit boards.” At that time, his other main materials included ordinary white craft glue and thick paint applied to scraps of wood.

However, he recalled, “After leaving school, I threw it all out and switched entirely from visual art to writing, since I didn’t have the space or the money for materials to make physical things once I’d left home. My current collage projects started around 2010, when ‘Robert Holcombe’ materialized as a minor character in a kind of alternative-history novel that [I had begun working on and] ended up abandoning.” The collage works Burrows/Holcombe has been making in recent years evolved out of that unrealized fiction-writing effort and “took on their own momentum.”

In the past, Burrows has lived and worked in Wales; Sheffield, another city in central England; and London. Robert Holcombe is, he explained, “an entirely fictional alter ego,” who was born in 1923 and died in 2003.

Credited with nearly all the collage artworks in the archive of Burrows’ oeuvre, Holcombe, his creator said, “has his own backstory and existence in the wider, postwar era.” Holcombe’s biography, he noted, “is slightly touched by science fiction,” and its details are “kept very much separate from my own biographical information and personal experience, so I guess that, on some level, I manage the archive and estate of a fictional artist, whose work I make behind that mask.”

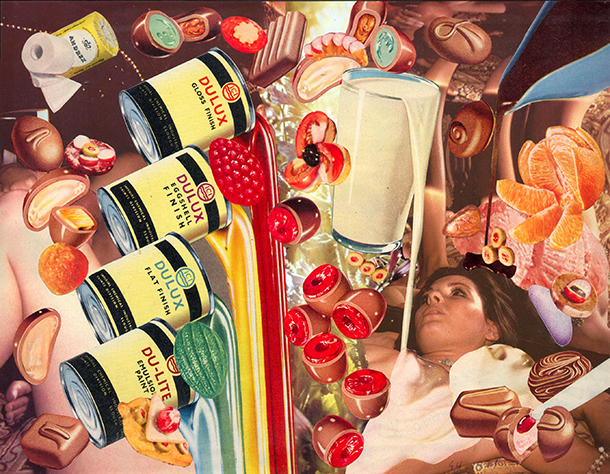

Holcombe’s meticulously executed collage compositions are filled with references to nature, history, and art. Many of them are quite dense, packed with images of subjects lifted from classical paintings, historical figures and events, consumer products, and buildings. In one early collage work from 1976, from the artist’s “Folklore Series,” with the improbable title “The Animals’ Revolutionary Council Proclaims the First London Cross-Species Socialist International to Humanity During the 1926 General Strike,” a giant octopus, several big birds, and masses of human demonstrators gather in a large urban plaza to support their cause.

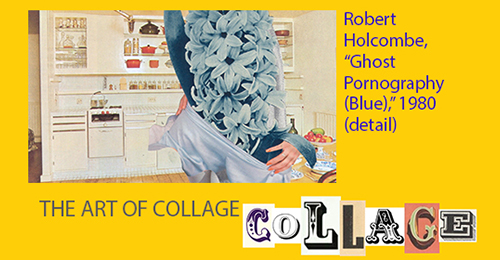

In “Ghost Pornography (Blue)” (1980), the torso and head of a female figure standing in a modern kitchen appear to be replaced by a bouquet of tall flowers shooting out of a simple frock — or is a woman wrapping her arms around this overwhelming column of plant growth? This element of this Holcombe work does recall the unexpected image juxtapositions of the kind Ernst conjured up in his experimental visual novel Une semaine de bonté (A Week of Kindness), which was first published in 1934 and consisted of collage compositions made up of images clipped from Victorian books.

About Robert Holcombe’s art, Burrows pointed out that all of his alter ego’s collage works “are made on paper mounted on board and are usually glazed and framed.” Since Holcombe is a made-up character, his artworks’ “dates of composition are also fictional and situate the works within the artist’s fictional timeline and archive” rather than within the period of time in which Burrows actually created them, which was between 2012 and 2020.

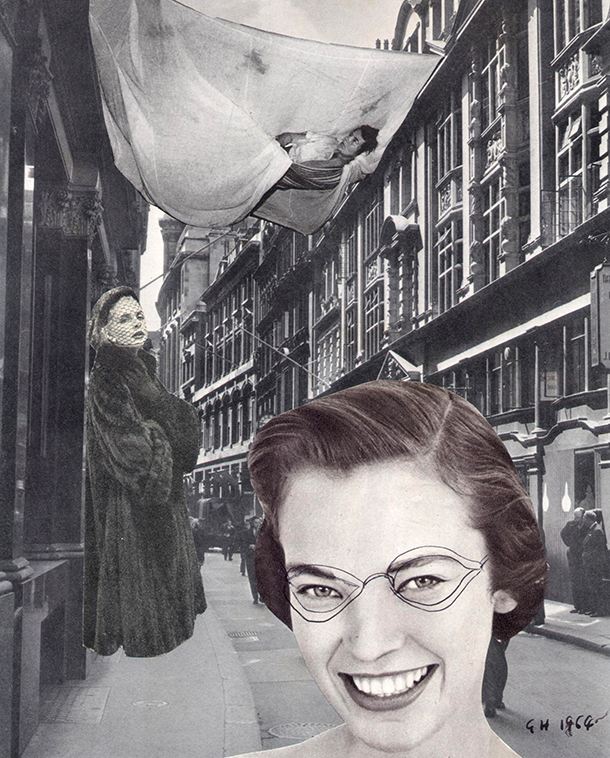

Burrows also observed, “Many of the pieces also work in sequential or series form, as indicated in their titles: ‘Folklore Series,’ ‘Telekinesis Series,’ etc. Some of these series span multiple fictional decades and hundreds of images, while others are more contained. For example, ‘The Holcombe Family Bible’ series includes around 60 images, all dating from a fictional 1967, while ‘The Buried Moon’ is an undated series of six images, and ‘The London Girls (Defaced)’ is a set of four images dated 1964.”

Burrows is aware that this Holcombe-related art history can seem a bit confusing — and so much the better, too. He said, “It is all contrived in this particular, rather convoluted way precisely because generating confusion over questions about reality, fiction, myth, folklore, authenticity, and authorship are a large part of [this body of] work’s founding and ongoing intention.”

Long live the cutting-up, no-restrictions approach and ethos of collage!

Burrows told us: “I think the reordering of existing historically and physically situated materials into new forms and patterns carries layers of meaning that painting, drawing, or digitally constructing similar kinds of images can’t really reach. The fact that I can use materials from the periods when the fictional Holcombe’s work was supposedly being made and fully ground it in, say, the 1950s or 1970s, even while using scissors and glue to create a slightly anachronistic digital seamlessness out of purely analogue materials and techniques, is a big part of the temporal distortion and sense of blurring between reality and fiction I want the works to create.”

Long live collage’s subversive spirit, too!

About what he’s been up to, bringing a master’s touch to some very artistic mischief, Burrows/Holcombe said, “I do think that can only work in the way I hope it does using collage.”