SOME EXPERIENCED PURVEYORS OF SELF-TAUGHT ARTISTS’ WORKS, MOST OF WHOM ARE COLLECTORS THEMSELVES, SHARE THEIR ANALYSES AND TIPS

by Edward M. Gómez

Art fairs are bazaars, where participating galleries aim to sell, and many a collector hopes to make some rewarding discoveries and score some good deals. Addressed to an art dealer eager to make a sale, “Can you offer me a discount?” is a question that spills automatically from many a veteran collector’s lips immediately after he or she has stumbled upon a must-have, love-at-first-sight find.

Perhaps uniquely among contemporary-art fairs, the annual Outsider Art Fair serves as much as a commercial fiesta as it does a gathering place for the wide range of players who are involved, as specialists, in the kind of art it celebrates — dealers, collectors, curators, educators, artists, interested media representatives, critics — and as a forum for the lively, often contentious debates that are always percolating in the outsider art field.

This year, for example, the related bogeyman terms “outsider,” “outsider art,” and “outsider artist” are again — or, more precisely, still — being argued over with an odd combination of been-there-done-that fatigue and renewed vigor.

Long before the predilections and proscriptions of hard-minded, ideological, so-called woke consciousness commandeered just about everyone’s thinking about just about everything in the art world, the outsider art sector’s regulars already were debating whether or not their field’s very name had become a label that sounded pejorative.

Does its use imply — or, worse, guarantee — that art-makers identified as “outsiders” will only become further marginalized if they’re tagged with such an apparently stigmatizing sticker?

As the 2023 OAF opens in New York this week, we had some other topics on our minds. We explored them in a series of interviews with several of the art dealers and other exhibitors who will be taking part in this year’s fair. Here is a round-up of some of their observations and analyses, all of which, together, suggest that their field is still as aesthetically effervescent as ever.

First we asked our sources in the outsider art field if, in the year that has passed since last year’s OAF, and with the worldwide coronavirus pandemic waning, they have noticed any trends in their specialized sector of the broader art market that might provide some clues about where it could be heading. We posed this question with a nod to the activity of certain, so-called blue-chip contemporary-art galleries that have become increasingly — and quite visibly — involved in presenting and selling the work of well-known, emblematic outsider artists.

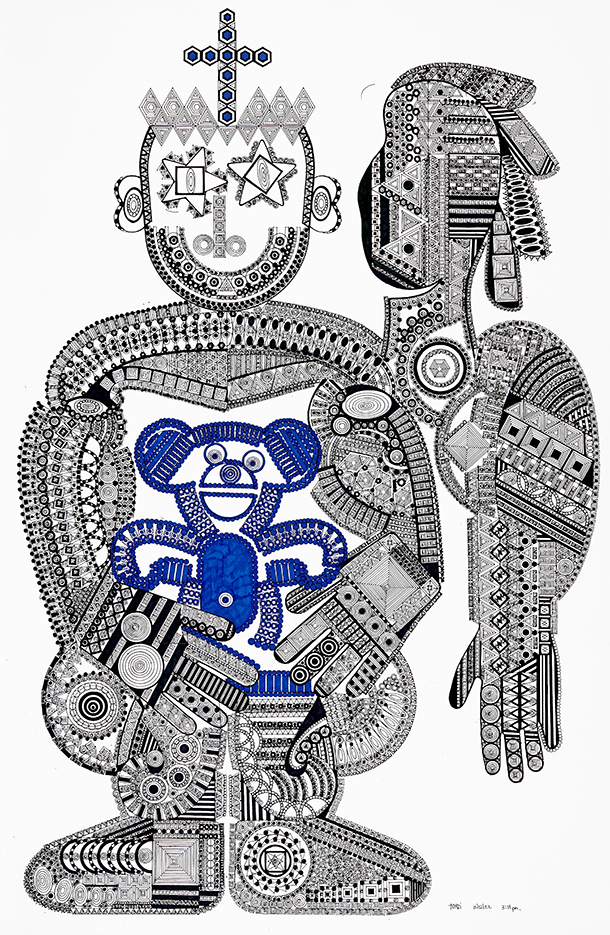

John Ollman of Fleisher/Ollman in Philadelphia, a gallery that, starting decades ago, has played a notable role in developing a market for outsider art in the United States, said, “I definitely think that such major galleries have impacted the pricing of [the works of] the artists they represent. [However,] I’m not certain [that such success for those galleries’ own artists] has carried over to other self-taught artists. I tend not to look at trends. Anthony Coleman is an Instagram sensation, but I think his work warrants the attention he’s receiving.” (Coleman, a native of Philadelphia, is a self-taught artist whose bright color-pencil drawings often rework the images of familiar cartoon characters.)

The dealer Andrew Edlin, whose eponymous New York gallery shows art made by both schooled contemporary artists and some of their best-known, self-taught peers, both concurs with Ollman and offers a slightly different assessment at the same time; he noted, “The participation of major contemporary galleries in our genre is part of the well-oiled ‘validation machine’ that has always existed in the art world. These galleries, given their resources and constituencies, can push up prices, which they also need to do, given their [typically] sizable overhead costs. This is Art Dealing 101. Outsider art dealers are paying attention, and works by their artists have risen as a result.”

Dealer Frank Maresca of Ricco/Maresca Gallery in New York, another longtime specialist in outsider art, remarked, “In the last three years, both Black Lives Matter and COVID have had the biggest effect on the field. Sales remained strong during the pandemic, but the way in which business is done has changed — at least for us. Pre-COVID, we almost never sold anything from online viewing rooms, but post-COVID, sales are now almost always initiated this way. [Today,] the attention artists of color are receiving across the board is unprecedented, and prices continue to rise. I think at some point everything will become more ‘normal.’ The only [aspect of any artist’s work] that should matter is its excellence.”

About the increasing handling by blue-chip contemporary-art galleries of outsider art, Randall Morris, who, with Shari Cavin, leads New York’s Cavin-Morris Gallery, another legacy gallery in the field, observed, “This may, of course, somewhat push up the prices of those deceased artists [whose works such galleries are handling] primarily, but it has not really touched prices across the board. It’s the same anywhere: The scent of money-blood draws the sharks closer.”

In our second question to outsider art dealers, we asked if the increasing involvement of blue-chip contemporary-art galleries with outsider art has affected how such art should be presented. That is, since such galleries show work made by both schooled contemporary artists and some self-taught/outsider artists, how challenging has it become to present the work of self-taught/outsiders in the context of contemporary art without necessarily emphasizing their self-taught/outsider status?

At the same time, how can or should dealers call attention to such artists’ special status and backgrounds, for, after all, those aspects of their life stories are essential to who they are and to the art they have produced?

Tom di Maria, who for many years served as the executive director of Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, California, with its model art workshop for disabled people, recently retired. Today, he has taken on the role of that organization’s director emeritus. Over a period of several decades, di Maria and his collaborators at Creative Growth patiently — and in an informed manner, strategically — brought the works of their most notable art-workshop participants to the international contemporary-art market without really emphasizing the particular status of their makers.

Di Maria told brutjournal, “There are definitely stigmas associated with being a person with disabilities, and they continue to impact the lives of our artists. Yet great strides are being made in advancing the ideals of disability justice, and more barriers are being broken all the time. Likewise, the stigmas associated with art made by people with disabilities are also falling to the sidelines, and there now exists a growing interest and enthusiasm for such work. As labels become more fluid and less specific, [this trend will] open up opportunities for artists with disabilities to be seen in a variety of contexts, ranging from those of the outsider, disability, and contemporary [categories]. This was not the case a decade or two ago.”

Randall Morris noted, “Our gallery presents the art first and then lets the people who need to categorize fight it out. We must always educate ourselves and our clientele to be aware of the differences ([between such descriptive labels as] ‘brut,’ ‘singulier,’ ‘neuve invention,’ etc). People have the choice to specialize or to cross over [genres] in their collecting. We discuss from the artist outward, not from the art world infrastructure inward ([referring to the] market, etc.). I prefer to present the whole artist, from quality to context.”

Carl Hammer, the head of the Chicago gallery that bears his name and another longtime specialist in the outsider art field, said, “Rarely, if at all, do I have to point out the uniqueness of the genre. My collectors and audience have all gotten over the ‘self-taught means inferior’ syndrome. Indeed, I feel that [the contemporary-art sector’s increasing interest in outsider art] has created a sense of awe and a willingness to accept the genre on an equal footing.”

Frank Maresca put it plainly, noting, “What turns me on are the conversations that emerge between dissimilar works of art.”

The New York-based dealer Marion Harris pointed out that the more contemporary-art galleries show the work of unschooled self-taught artist, the more natural it will become to show such art alongside that of academically trained artists. She said, “A good example can be found in We Are Birds, a curated exhibition that will be on view at the Outsider Art Fair this year, including works by both self-taught and trained contemporary artists. Two of the trained contemporary artists I represent, Susan Halls and Andy Malone, both of whom are British, have work on view in this show.”

Finally, we asked our art-dealer contacts if longtime, experienced collectors of outsider art are still approaching the field with the wide-eyed enthusiasm that led them into it years ago or if many of them now tend to think, “That’s enough. I’ve built my collection. Now I’ll only acquire an exceptionally rare and interesting artwork.”

At the same time, we asked them to share any advice they might have for collectors who are just beginning to acquire outsider art, which now represents a well-developed sector or the art market and the broader art establishment.

John Ollman told us, “Most serious collectors look for the best possible examples of the works of the artists they love. Others just want everything. I’m on the side of quality over quantity. I do push a bit if I think someone is building a collection, and there is a significant hole. But in the end, the collector has to want the work to be represented in their collection.”

Ollman’s advice to novice collectors? “Study the artists [to whose work] you respond, read everything you can about that artist, figure out your budget, and buy the best work or works you can. Great collections are built over time. Don’t be afraid to make ‘mistakes,’ because one’s taste will probably change. Follow your instincts. Curate your collection with your eyes and your head, not with your ears.”

The young British art dealer Jennifer Gilbert, who is based in Manchester, in the north of England, and operates the itinerant Jennifer Lauren Gallery, began taking part in the annual Outsider Art Fair a few years ago.

She said, “My advice would be to trust your gut instinct. If you like something [that you see at the OAF], maybe get the dealer to hold it for an hour, and make sure you do a lap around the fair to be sure it is definitely the piece for you. Chat with the dealer, who might have articles about the artist you can read to help you make a decision. A work doesn’t need to be made by the most famous artist; if it speaks to you in some way, or if you feel an emotional response to it, I often think that is the best way [to determine whether to acquire it or not]!”

Matthew Murphy, who oversees the art workshop for disabled people at LAND Gallery, in Brooklyn, advised: “First-time collectors or those who are new to the fair should take their time. Explore and keep an open mind. Collecting is about being surprised by something, and with the variety of booths that are present at the fair, something might compel you to pause [and examine it].”

Murphy noted that the various price points at which works of art are made available at the fair offer collectors different points of entry into a vibrant market.

After many years of showing and selling art, and as an experienced collector himself, Frank Maresca offered these bons mots: “Collecting has to do to with passion, age, and money, and to a lesser extent, with your available space. I know very few collectors under the age of 30 and older than 80. In any case, the answer is always the same: Buy what you love. Acquiring art must be a need. If you don’t need it, there are many other things you can do with your money. If you have a need and the desire, the question [about what to acquire for your collection] answers itself.”

[See our exclusive preview of the 2023 Outsider Art Fair New York, focusing on what art dealers and other exhibitors will be showcasing at the big event. Look for that separate, free-access article on brutjournal’s home page. Go get it!]