A DYNAMIC RESEARCHER AND PROMOTER OF SELF-TAUGHT ARTISTS’ CREATIONS SHARES SOME OF HIS BIG FINDS WITH US

by Nobumasa Kushino

(Original text in Japanese translated into English by brutjournal Editor in Chief Edward M. Gómez)

Born in 1976, Nobumasa Kushino currently lives and works in Shizuka Prefecture, in southeastern Japan. Since 2000, in addition to his work on the staff of a social-welfare organization serving people with intellectual disabilities, he pursued various art-promoting activities, and beginning in 2012, as a curator, he was associated with the Tomonotsu Museum in Fukuyama, in Hiroshima Prefecture.

Thereafter, in order to promote certain deserving forms of expression that were not already well known, in 2016, he founded the gallery Kushino Terrace in Fukuyama. To date, he has done original research about more than 400 artists, and not only those who are disabled, introducing them through projects that have been presented throughout Japan’s art scene and in other settings.

His books include, among others, Autosaido de ikite iru (Living on the Outside, Taba Books, 2017) and Autosaido Japan: Nihon no Autosaidaa aato (Outside Japan: Japanese Outsider Art, East Press, 2018).

In 2021, Kushino took up the post of chief program director for the Shizuoka Arts Council. Kushino is the recipient of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Prize from the eponymous government agency that sponsors this award. He has curated numerous exhibitions of Japanese self-taught artists’ works at various venues around Japan.

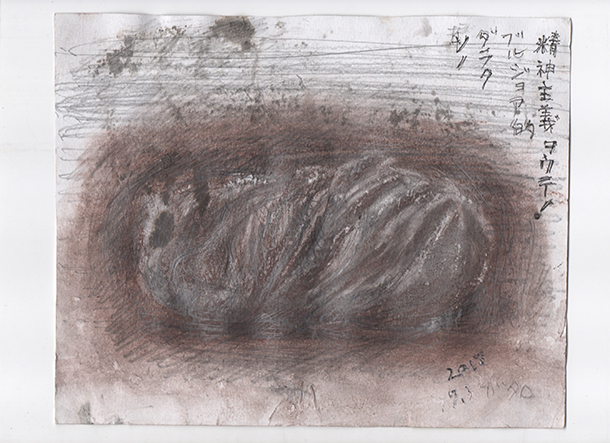

Gataro

born 1949, lives and works in Hiroshima Prefecture

Gataro has called himself “kappa,” a word that refers to a mythical, water-dwelling creature, and “trash picker.” After graduating from high school, he worked at various jobs — at a printing-plate-making company and as a postal-mail deliverer, a bouncer, and a day laborer. At the age of 33, he started working as a janitor in a shopping center in the municipal Motomachi Apartments in the city of Hiroshima. Since then, for more than 35 years, every morning from 4:00 a.m. to around 9:30 a.m., he has carried out his janitorial work. After finishing his tasks, as if feeling the beauty of the cleaning tools he employs to do his job, he uses crayons and other items he has picked up to make sketches.

In his “Dust Cloth Scores” series (2018-20), picking out various faces by freely using a cleaning rag, he combined his own figure and the perspective of other disadvantaged people in self-portrait-like pictures. Emulating the composition of Vincent van Gogh’s painting “The Potato Eaters” (1885), in his own “Kawazoko no uta” (“Riverbed Song,” 2019), Gataro depicted socially disadvantaged people gathered around a yaminabe meal (a stew prepared from ingredients provided by the participants in a dinner party).

Click here to see a brief video, produced by Nobumasa Kushino, showing the artist Gataro at work (available on YouTube).

Shūhei Tsuji

born 1977, lives and works in Tokyo

Having failed three times to gain admission to Tokyo University of the Arts, starting in 2000, Shūhei Tsuji ran his own Sengoku Gallery in the space of a former tofu shop that he had rented. At that time, knowing about Picasso to some extent but having absolutely no knowledge about drawing, at his gallery he began making his own pictures. In the summer of 2012, when his grandmother’s 40-year-old house became vacant, he remodeled it and there installed his new Asakura Gallery. The roughly 10-tsubo-large (about 356 square feet or 33 square meters), two-story building was painted throughout and uniformly in shocking pink. He created a slide and numerous art objects.

The entire house became one big work of art. In this atelier-cum-living space, on every day of the week except Wednesday, Tsuji continues creating art. Being interested in what is known in Japan as “girls’ culture,” he has produced many pictures whose subjects are his ideal women with large eyes.

He failed to pass the university entrance exam three times in the past (when he supported himself through part-time work) and, since that time, has not had other work experience, nor has he exhibited his work in solo or open-call, group exhibitions. Tsuji says, “Even though I don’t know what I’m going to be painting next, I’m not worried about the future.”

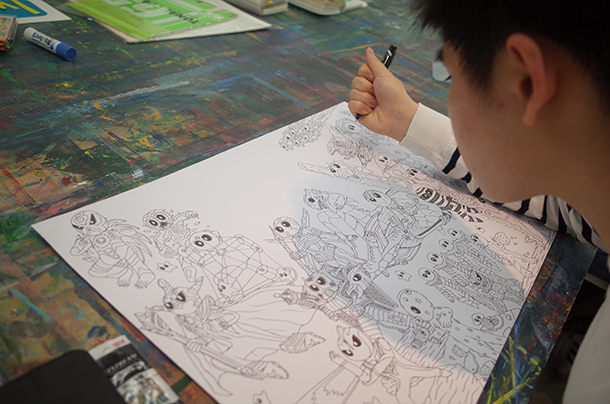

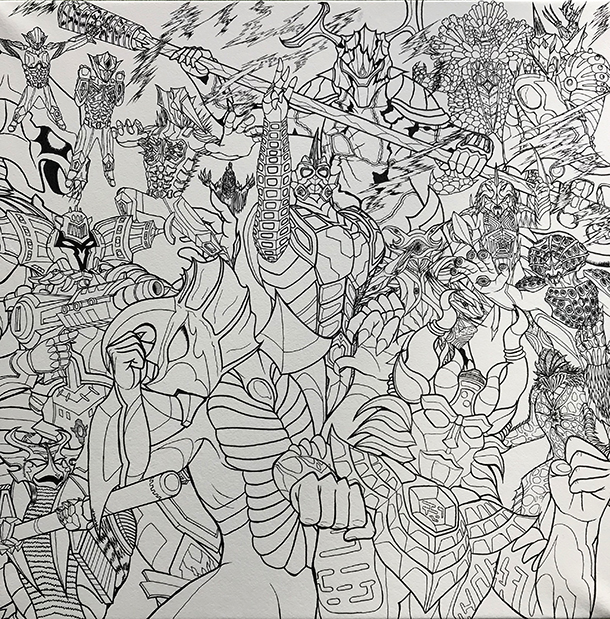

Motoki Yagi

born 2002, lives and works in Kanagawa Prefecture

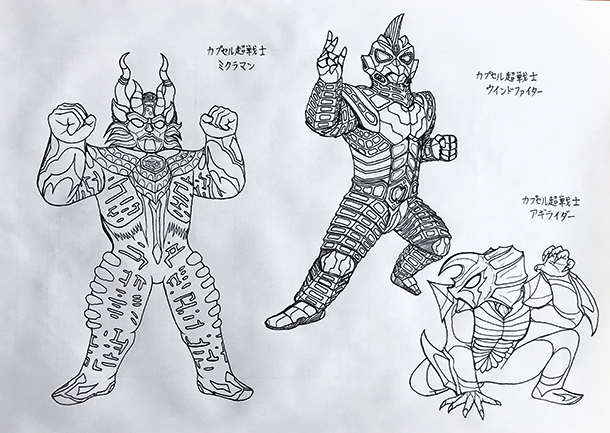

Because, when he was a child, he was not able to express himself very smoothly, Motoki Yagi drew pictures to call his mother’s attention to his needs. Since then, he has spent more than half of his time at home making drawings; he has made many on the back sides of used documents his mother has brought home from her workplace. There was a time during his elementary-school years when Yagi enjoyed making copies of Ultraman; that was back when that comic-book character was first introduced.

Without making preliminary sketches and using only a black ballpoint pen, he draws countless, large-scale pictures of large gatherings of monsters, his pen racing to depict, with imagination, the limbs of even the monsters who appear toward the back of his compositions. At such times, when his drawing line reaches the edge of his paper, he uses cellophane tape to attach additional sheets and expand his drawing surface.

In recent years, further advancing his drawing technique and still using only a single ballpoint pen, Yagi has continued drawing monsters in such works as his “Tekunomeka” (“Techno-mechanical”) and “Devilish Beasts” series. Sometimes, still without making preliminary sketches but with deliberation, he draws very fine, three-dimensional-like lines. Always assigning names to his monsters and robots, he continues creating his works for himself and shows no signs of ever wanting to stop.

Itsuo Kobayashi

born 1962, lives and works in Saitama Prefecture

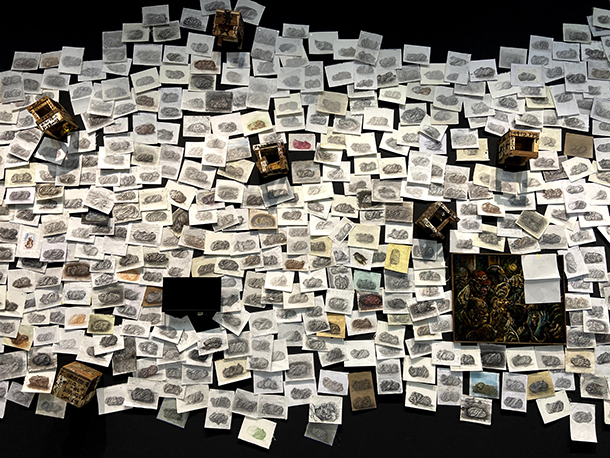

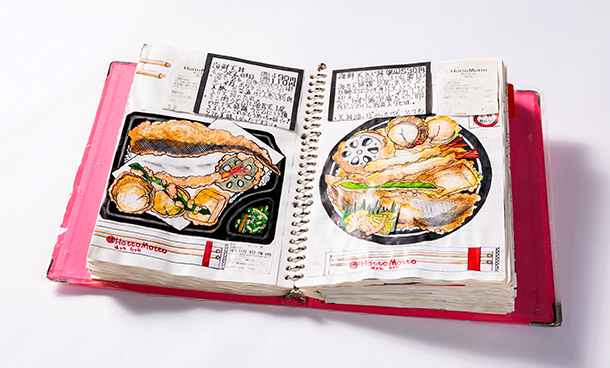

After working until the age of 46 as a cook in a downtown soba restaurant and lunchtime service center, Itsuo Kobayashi began suffering from the effects of alcoholic neuropathy, which affected his ability to walk. Relying on written notes he had been gathering since he was 18 years old, starting around the age of 26, he began summoning his memories of earlier times to routinely make drawings recording his impressions of the meals he has eaten. With his art-making supplies piled up around his bed, after he finishes eating a bentō take-out meal, he removes any seashells or crabs’ legs, disposable chopsticks, or unused condiment packets [from his tray] and lines up such items as though they were his raw materials.

Because it’s hard for him to go out, he often orders home-delivery meals or asks his mother to go buy and bring back take-out meals. Then he comes up with each new composition in his ongoing “Chopsticks-holding Hand” series. To date, he has produced more than 1000 such drawings whose compositions, typically, offer a view looking down at all of his accumulated food items. Furthermore, by writing in the blank spaces of his drawings the names of each meal’s dishes and ingredients, and the price of and his impressions of each meal, later he can enjoy fond memories of what he has eaten, which are notated with such affirmative words as “delicious.”

Click here to see a brief video, produced by Nobumasa Kushino, showing the artist Itsuo Kobayashi at work (available on YouTube).

Yasuhiro Tomohara

born in 1950 in Hyōgo Prefecture; date of death unknown

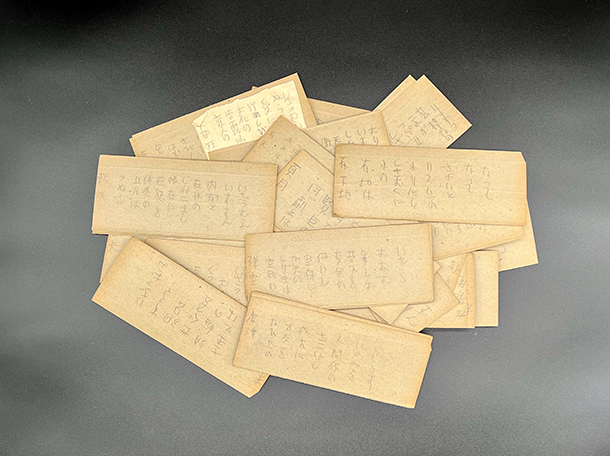

After writing a poem titled “The Back Side of the Chalk Box is Pretty” in junior high school, Yasuhiro Tomohara met the former Gutai Art Association member Shozo Shimamoto, who was then teaching at that school and offered the youngster encouragement. [Editor’s note: The Gutai Art Association was a group of young, avant-garde modern artists who were active from the mid-1950s to the beginning of the 1970s in the Kansai region of southwestern Japan.]

Coining the phrase “Iza, tsumue,” meaning “Come now, let’s go!”, Tomohara wrote many poems on pieces of corrugated cardboard. In 1965, when he was a third-year student in junior high school, he appeared as a prodigy child on a television program, where he composed improvised poetry with tremendous speed, a performance that attracted considerable attention.

Thereafter, although he continued composing poetry with great concentration, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia and, when he was 23 years old, was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where, after taking medicine and undergoing electroshock treatment, he stopped writing poems. Later, after having resided more than 30 years in a single room in what had become a shut-down hospital, his life came to an end.

Yasuki Inada

born 1949, lives and works in Shizuoka Prefecture

After graduating from university in 1972, Yasuki Inada worked for a large manufacturer of electric appliances and, as the person responsible for its air conditioner production department, was assigned to the company’s factory in Fuji (a city in the eastern part of Shizuoka Prefecture). Starting in 1995, he worked as the company’s representative in Bangkok, Thailand. To avoid giving in to the temptations that tended to attract foreign workers there and to discipline himself, in his own room, he began making still-life drawings.

After retiring from his job and receiving praise for the sketches he was making as a hobby, starting at the age of 67, based on his visits to the city in which he was living and to Tokyo, he began drawing his “Crisis Series,” which depicts very large, living creatures.

Having made some 20 works so far, the influence on his work of that of the artist Akira Yamaguchi, whose meticulously rendered aerial-view drawings he very much admires, and of his experience over many years in manufacturing-production development has been considerable. In recent years, by distorting the backgrounds of his pictures and through other techniques, year after year, he has continued developing his compositions.

Resources

Website of the Japan-based gallery Kushino Terrace, which was founded by and is operated by Nobumasa Kushino; click here.

Website page of the publisher of Nobumasa Kushino’s book Autosaido de ikite iru (Living on the Outside, Taba Books, 2017); click here. Links are provided to several Japan-based online retailers from whose websites this book may be purchased.

Website page of the publisher of Nobumasa Kushino’s book Autosaido Japan: Nihon no Autosaidaa aato (Outside Japan: Japanese Outsider Art, East Press, 2018); click here. Links are provided to several Japan-based online retailers from whose websites this book may be purchased.