A FLORIST AND A PHOTOGRAPHER TEAM UP TO CREATE IMAGES OF PLANT FORMS AS EPHEMERAL JEWELS

by Edward M. Gómez, in dialogue with Leslie LeFranc and Kaitlyn Danielson

The photographer Kaitlyn Danielson (Instagram: @kaitlyndanielsonphoto), who was born in the United States and grew up in Israel, began her creative adventure in the making of images when she received, as a gift, a 35-millimeter camera that had formerly belonged to her grandfather. She went on to study photography and video at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where she reveled in the hands-on nature of darkroom printing processes.

She became especially interested in such historical methods of photo-image-making as wet-plate collodion (which refers to the preparation of photographic plates with photosensitive emulsion, a technique Matthew Brady used to make his now-classic photos of soldiers in the U.S. Civil War), salt printing, and the use of gum bichromate for “gum printing,” which gives photo images a painterly effect.

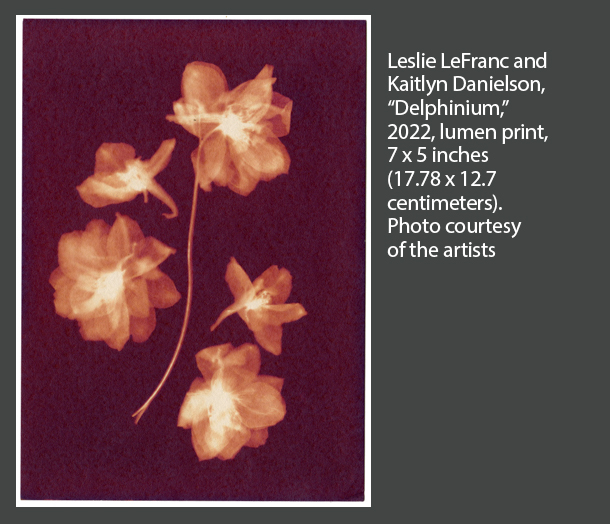

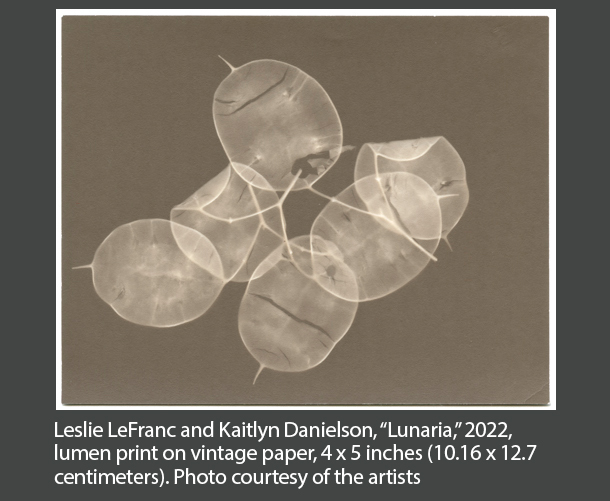

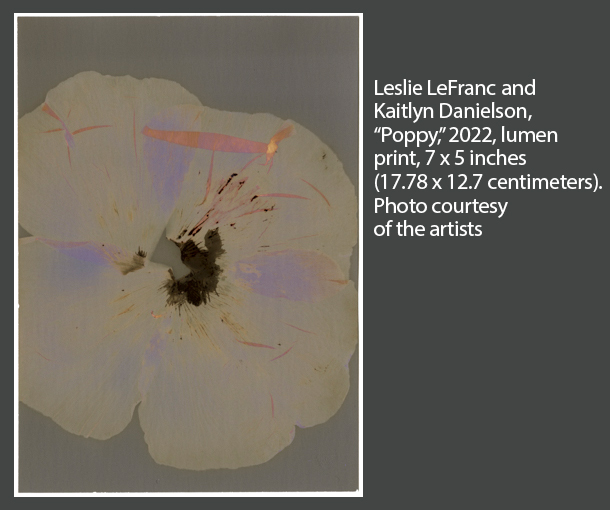

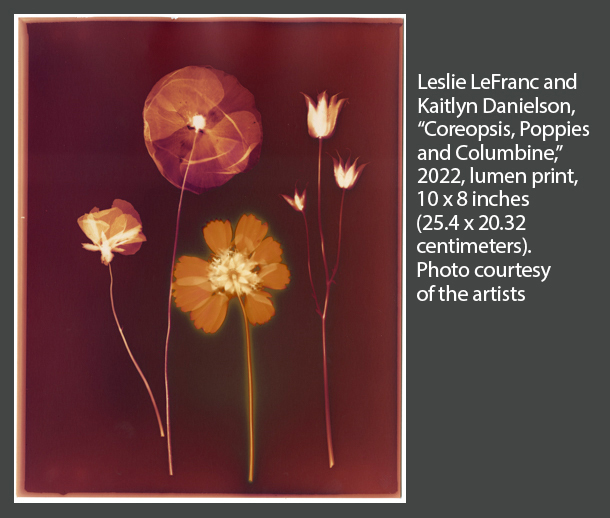

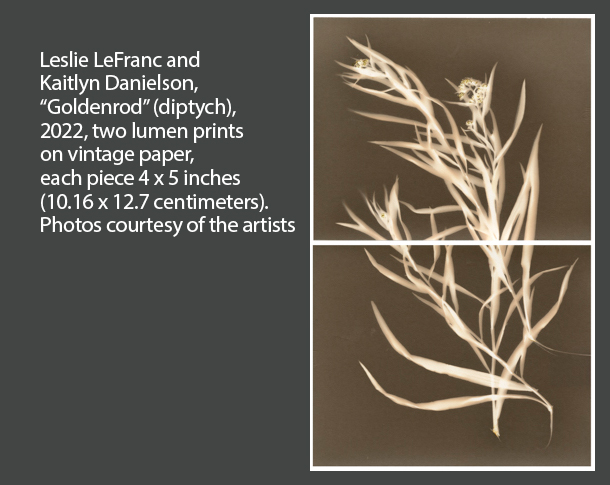

For several years now, Danielson, who is based in New York State’s Catskill Mountains region, has collaborated with Leslie LeFranc (Instagram: @touche_a_toutgardens), who, with her husband, Maurice, owns and operates Touche-à-Tout Gardens, a ten-acre flower farm in northeastern Pennsylvania’s Upper Delaware River Valley Highlands. With LeFranc providing the flowers and Danielson overseeing the technical processes, they have produced a range of lumen prints, which are also known as solar photograms, or images produced by placing objects on photosensitive paper or other surfaces that are exposed to direct sunlight. They have given their series of resulting photographic works the title “Pressed in Light.”

No cameras are used in the making of photograms, whose resulting imagery can appear opaque when it has been produced using solid objects. By contrast, photogram imagery can appear translucent — or even, in a remarkable, ghostly-beautiful way, transparent — when it has been made using such organic subject matter as plants.

Danielson told brutjournal: “The power and beauty of nature are huge sources of inspiration for me. I have hiked the mountains of Peru, bathed under waterfalls in Norway, worked on farms in Italy, and stargazed in the Texas desert. I cannot imagine a life without access to nature in some way. Much of my artwork is influenced by the natural world — directly, in my subject matter, or aesthetically, with regard to shapes, textures, and color palettes.”

In a separate recent interview, LeFranc recalled how she became a flower farmer. She said, “I earned a bachelor’s degree in fine art and literature, which led to a career as a print graphic designer, which I enjoyed for 35 years. After retiring nearly full-time from design, I moved to rural Pennsylvania, where I began my journey as a farmer-florist about five years ago. I have always wanted to work with flowers and, rather than resigning myself to ‘career over, now relax,’ I learned what I could by apprenticing and taking courses about flower farming and floristry. Failure is a big part of the learning process, which I experience every season, but from it I also gain valuable information.”

LeFranc added, “I’ve always had an abiding love of nature, which was instilled by my father, but mostly it came from spending every summer, from the age of 10 to when I was 20, in rural Vermont, working on a farm. Aesthetically, I’m drawn to the myriad shapes, sizes, colors, and textures of flowers and plants, and, as a graphic designer, I try to incorporate as many of those elements as possible into any given commission or editorial spread. I’m particularly interested in the tension that results from working with the lowliest of weeds or wildflowers alongside highly cultivated flowers, which allows their different textures, sizes, shapes, and colors to inform and guide my design.”

About the duo’s artistic collaboration, Danielson explained, “Leslie and I met several years ago and immediately connected as friends. After visiting her flower farm and seeing her collection of dried botanical specimens, we started brainstorming on ways in which we could combine our skills in some kind of art project. We did our first experiments with lumen prints in 2020 and we’ve continued working together ever since then.”

About their working methods, she noted, “A decision about which plants to use comes first, after an initial infatuation with the specimen. That leads to experimentation and lots of trial and error to create a final piece. Personally, I’m drawn to abstraction and often find myself working with layers or deconstructing the plant itself to create an image that is not fully recognizable at first glance.”

LeFranc also remembers how her collaboration with Danielson evolved and how it was based on their shared appreciation of — and fascination with — plant forms and flowers. She recalled, “Katie and I met several years ago at an artist’s lecture in the Catskills. We slowly started building a friendship, collaborating and bouncing ideas off each other. I don’t exactly recall the ‘Aha!’ moment when we came up with the flora photograms idea, but we dug in and worked on it, off and on, for two years.”

“We worked with my large collection of pressed and dried flowers, as well as with fresh ones from my field, which yielded surprising results, depending on the moisture content — or lack thereof — of the plant, and on weather conditions, the light source — sunlight, UV light, indoor or outdoor light — the exposure time, the age of the photosensitive paper (some of which was expired film), and on how the photo paper was processed in the darkroom. Sometimes we even treated the photo paper with water or vinegar. Some of the most exciting results came from plants you wouldn’t think twice about, such as craggy old weeds, lacy leaf stems, dried flower pods, and grasses.”

LeFranc noted that she finds inspiration in the work of such “pioneering women botanists and illustrators” as the German naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) and Jeanne Baret (1740-1807) of France, the first woman to complete a voyage of circumnavigation of the globe by sea.

LeFranc advised, “There is much to be gained by putting your hands in the dirt and growing a living thing from seed. And from sitting still, listening, and observing. As the author Robin Wall Kimmerer [a specialist in environmental and forest biology] says, in some indigenous people’s languages, the term for plants translates as ‘those who take care of us.’”

Danielson evoked the strong sense of artistic inspiration she finds in nature. She observed, “With this collaboration, ‘Pressed in Light,’ we want to highlight the simple yet profound beauty that can be found when you get close to the ground and look for it. A blade of grass, a milkweed seed pod, the veins in a leaf — you don’t have to look far to find wonder in the natural world. A flower can be just as awe-inspiring as the view from a mountain top.”