NAM JUNE PAIK IN FOUR MOVEMENTS

With dizzy TV images, mixed-media installations, robots, and more, a career-spanning retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art offers an overview of the work and ideas of “the father of video art”

By Sarah Fensom

U.S.A. West Coast Bureau Chief

I.

SAN FRANCISCO — Nam June Paik (1932-2006), the Korean-born multimedia artist, used technology to shrink the world. He frequently moved between cities — Seoul, Tokyo, Munich, New York — but strove to make work that connected all of them. Through his collaborations with an international roster of avant-garde luminaries — Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage, Charlotte Moorman, Shigeku Kubota (who became his wife), and others — and his embrace of such mass media as recorded music, television, and satellite feeds, sometimes, literally, he achieved that goal.

Now, Nam June Paik, a sweeping retrospective on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (through October 3, 2021), explores Paik from every angle: as a classically trained musician, pioneering performance artist, and “father of video art,” among other pursuits and accomplishments. Organized by SFMOMA and the Tate Modern, in London, in collaboration with the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and National Gallery Singapore, the Bay Area iteration of the show boasts more than 200 works whose collective spirit traverses media and national borders. (This survey will later travel to those other venues.)

Putting Paik’s video-art paternity front and center, the exhibition opens with “Button Happening” (1965), the artist’s earliest extant videotape, which is likely the first one of its kind that he or any other major artist ever recorded. Paik shot its footage the very day he acquired a Sony Portapak camera, a hand-held, battery-powered, analog videotape recording system that entered the market in 1967 and could be operated by a single person. That early video captures Paik repeating a single performative gesture — buttoning and unbuttoning his coat. This doing and undoing of buttons is played in a recurrent loop, creating a sense of connection and disconnection that seemingly goes unresolved in perpetuity.

Its performance aspect is linked to Paik’s association with Fluxus, the international collective of artists, composers, and poets who cooked up and participated in Neo-Dada experimental, audience-participatory event-art activities throughout the 1960s and 1970s. (The exhibition devotes an entire gallery to Paik’s formative involvement with that group.). Borrowing from Fluxus lingo the word “happening,” as it was used by Allan Kaprow to refer to performance events, some of which were loosely scripted, Paik’s “Button Happening,” like many Fluxus endeavors, emphasises process over final product.

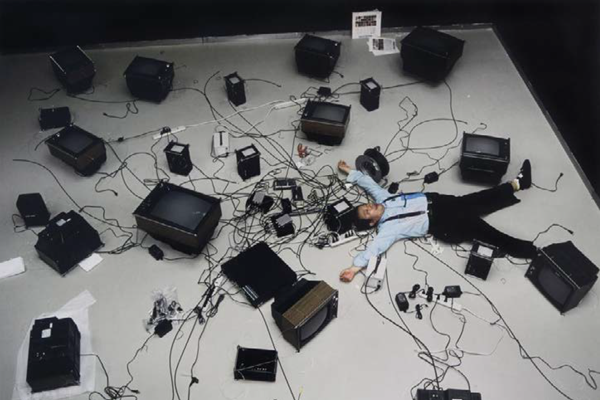

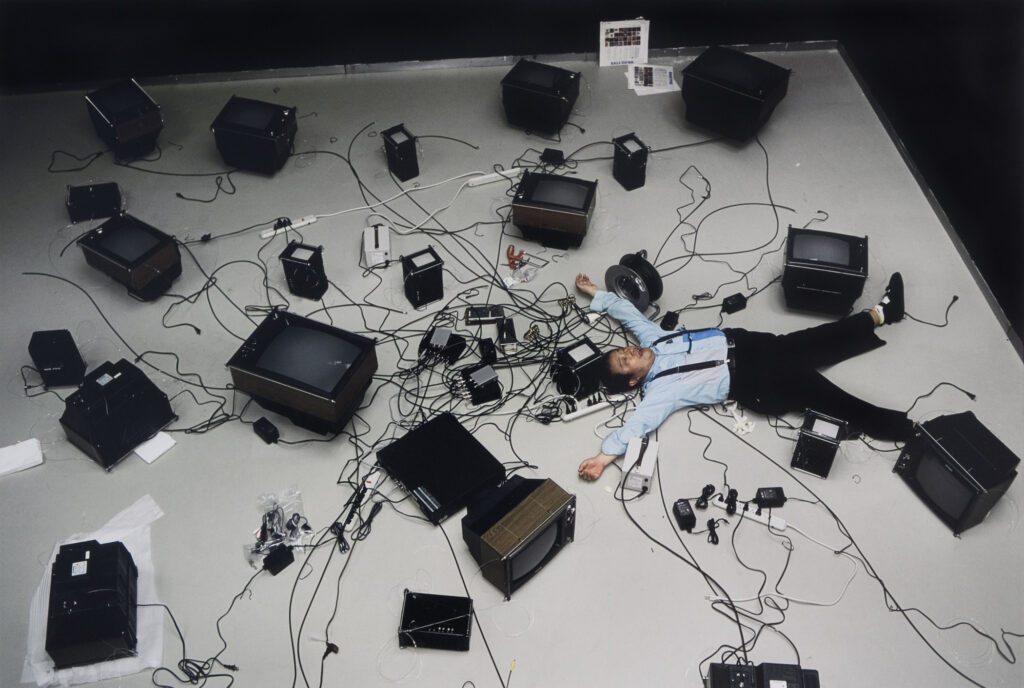

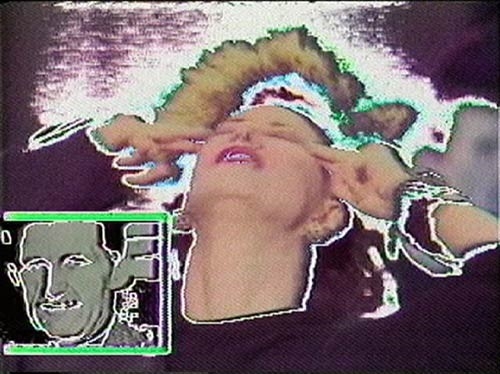

The video works Paik made throughout his five decade-long career are spangled across the galleries on the museum’s fourth floor. On view, for example, is a pair of single-channel videos Paik made in 1969 during an artist’s residency at WGBH-TV, the well-known public-television station in Boston. One of them, “9/23/69 Experiment with David Atwood,” created in collaboration with the station’s engineers and musicians, fuses live TV programming and pre-recorded material with pure electronic abstraction. Its companion piece, “Electronic Opera #1,” offers an example of what Paik called “participation TV,” in which the artist instructed audience members to open or close their eyes while he played a barrage of experimental video effects. This work was Paik’s contribution to “The Medium is the Medium,” a pioneering “artists’ transmission” produced by WGBH-TV. Broadcast in 1969, it featured video-art pieces by Paik and five other artists, including Kaprow.

Paik repurposed portions of “Electronic Opera #1” for “Global Groove” (directed by Merrily Mossman, 1973), a composite of avant-garde, pop, and commercial imagery and music produced by the TV Lab at WNET/Thirteen, New York City’s public-television station. This colorful, jubilant piece clocks in at 28 minutes and 30 seconds — about the same running time as that of a typical television sitcom. “Global Groove” features the avant-garde composer John Cage telling a joke about his dentist, a traditional Korean dance performance, Japanese TV commercials, and a leotard-clad troupe of tap artistes feverishly hoofing it, among other video non sequiturs.

On this visual onslaught’s soundtrack, the gentle tones of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” give way to the driving drum fills of Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels’ “Devil with a Blue Dress On.” “This is a glimpse of the video landscape of tomorrow,” a narrator states, “when you will be able to switch to any TV station on the earth, and TV Guide will be as fat as the Manhattan telephone book.” Swap the telephone book for a search bar and an endlessly scrollable Web page, and 1973’s “Global Groove” becomes today’s YouTube.

At SFMOMA, “Global Groove” plays on 49 TV sets displayed amidst lush potted plants in Paik’s “TV Garden” (1974-78). Commanding a whole gallery, “TV Garden” is a major installation that cross-pollinates technology and nature; that kind of mash-up became an on-going theme throughout the artist’s career. This large-scale work also serves as a powerful treatise on the power and character of television and new media, suggesting that, like flora and fauna, they are subject to wild growth and change.

Paik’s status as a “global artist” — he was a pioneer in that role, too — can be felt throughout this retrospective; it was reinforced by many details of his life story. Born in Seoul, in 1932, during the last decade of Japan’s colonial rule of Korea, throughout his youth, Nam June studied the piano and musical composition with Japanese-educated tutors. In 1950, during the Korean War, the Paik family fled its home and eventually settled in Japan. There, in 1952, Paik enrolled at the University of Tokyo, where he majored in aesthetics and wrote a thesis on Arnold Shoenberg. After graduating in 1956, he headed to Munich, where he studied musicology and art history, and fell in with West Germany’s experimental-music scene via the Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music.

Through his Darmstadt connections, Paik first encountered John Cage, who became his greatest artistic influence. The young Korean eagerly embraced Cage’s openness to chance and indeterminacy, as well as the American’s interest in Zen. Works that function as tributes to Cage abound in SFMOMA’s retrospective, such as “Hommage à John Cage, Music for Audiotapes and Piano” (1958-59), Paik’s first avant-garde musical composition, which plays on an outdoor terrace overlooking downtown San Francisco. Then there is Paik’s spare “Zen for Film” (1964), a blank piece of 16-millimeter film projected on a white screen — the young Korean renegade’s cinematic equivalent to Cage’s radically austere composition, “4’33”” (1952), in which the “silence,” or ambient sound, of a concert hall provided the audible “music.”

In 1958, Paik moved to Cologne. There, he took part in the painter Mary Bauermeister’s avant-garde salons and began collaborating with the avant-garde composer and electronic music pioneer Karlheinz Stockhausen. In his new milieu, he staged raucous performances showcasing his penchant for unpredictability. In 1963, he mounted his first solo exhibition, “Exposition of Music-Electronic Television,” at the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, West Germany. For that event, he transformed the three-floor gallery into a veritable freak show of immersive environments, interactive sculptures, and modified musical instruments, including three prepared pianos. The exhibition even featured a severed cow’s head — a reference to Korean shamanism. (In 1963, Paik made a trip to Japan, where he first met the Japanese-born artist Shigeko Kubota, an active member of Tokyo’s avant-garde scene.)

A year later, Paik relocated to New York. (So did Kubota, and in time they became a couple; they were married in 1977.) There, he collaborated with Charlotte Moorman, the Juilliard-trained cellist and performance artist, and took part in Fluxus-related and other experimental events that Yoko Ono and La Monte Young presented at Ono and Moorman’s loft at 112 Chambers Street, in downtown Manhattan.

Throughout the 1960s and into the following decade, Paik experimented with electronics, and the scope of his projects expanded. Satellite transmissions, robots, and giant figures made from TV sets entered his oeuvre. SFMOMA’s retrospective culminates in one of the artist’s grandest projects, his “Sistine Chapel” (1993), an installation featuring 40 projectors casting overlapping video clips on the walls and ceilings of a cavernous gallery. Its soundtrack alternates between loud music and silence.

Paik developed this multimedia extravaganza for the German Pavilion at the 1993 Venice Biennale. Inspired by Marco Polo’s late-13th-century journeys along the Silk Road, he created a variety of works for that high-profile event, in which “Sistine Chapel” served as a lavish centerpiece. For that installation, he remixed some of his earlier video pieces to create tracks that played on repeat. Seen today, Paik’s energetic image collage still feels like a time-bending journey from West to East that hops from one culture to another, from the avant-garde to pop, from one decade of Paik’s career to another, and then back again to its various starting points.

Paik used the term “random access” to describe his à la carte approach to mixing diverse cultures and technologies. He believed in media theorist Marshall McLuhan’s “global village” —the idea of bringing the world together through networks of shared information and telecommunications. In his personal and work-related travels, Paik moved across continents and oceans; by experiencing his art, he invited audiences to vicariously do the same.

II.

In 1974, Paik coined the term “electronic superhighway” — long before Al Gore adopted it a few decades later. The artist believed a decentralized, global system of information exchange could prove to be revolutionary, and the notion he promoted presaged later, broad understanding of digital networks. In the United States, John Naisbitt, a trend forecaster who released the best-selling book Megatrends: Ten New Directions Transforming Our Lives in 1980, helped spur the public’s grasp of the term “electronic superhighway,” predicting the emergence of a postindustrial society that would rise from the ashes of economic recession and lead to a digital revolution.

In Naisbitt’s vision of the future, which was widely embraced by both neoliberals and free-market conservatives during the deregulatory Reagan years — British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the Republican politician Newt Gingrich were vocal fans — an information society and global economy would walk hand in hand into a prosperous sunset.

Critics panned Megatrends, with one dismissing it as the “literary equivalent of a good after-dinner speech.” Still, Naisbitt’s broader predictions attracted some serious attention. As it turned out, his divinations about what would become the Internet were largely on target, even if, in retrospect, his overly optimistic view of the eventual effects and political ramifications of his prognostications turned out to be more off base. For instance, Naisbitt believed that the coming digital society would offer plentiful job opportunities for all. He also claimed that it would no longer matter who served as president of the U.S., a prediction the last decade of American history clearly has disproved.

Naisbitt balanced his notions of “high tech” with a concept called “high touch,” which stressed the warm human element necessary for a functioning digital society. Despite coming from highly divergent starting points, one middle-brow, the other avant-garde, regarding this particular notion, Naisbitt’s thinking and Paik’s did intersect.

In Megatrends, Naisbitt wrote: “Whenever a new technology is introduced into society, there must be a counterbalancing human response — that is, high touch — or the technology is rejected. […] We must learn to balance the material wonders of technology with the spiritual demands of our human nature.”

Similarly, in 1986, Paik told the New York Times: “Our life is half natural and half technological. Half-and-half is good. You cannot deny that high-tech is progress. We need it for jobs. Yet if you make only high-tech, you make war. So we must have strong human element to keep modesty and natural life.”

In the 1960s, Paik experimented alongside scientists at Bell Labs in Holmdel, New Jersey. Using early-model computers, he created purely digital artworks; evidence of those creative efforts is on view in the retrospective, however, Paik ultimately abandoned working entirely in code. After all, digital technology’s binary system did not allow for the human element he felt his projects required.

By contrast, Paik’s international satellite transmissions, which might appear quaint in today’s era of instantaneous, global everything, command their own viewing theater within the exhibition. These productions harmoniously combine high technology with bedrock examples of human cultural expression: dance, music, and conversation. Paik’s first transmission, “Good Morning Mr. Orwell,” was initially broadcast on New Year’s Day 1984. It linked live events in the U.S., France, and Germany, and mixed them with pre-recorded segments. Doing more than just bridging countries through a worldwide broadcast, Paik’s colorful spectacle also mashed up high art, popular culture, and television’s notoriously low-brow sensibility. Such artists as Merce Cunningham, Peter Gabriel, Allen Ginsberg, and Laurie Anderson all appeared in Paik’s ambitious extravaganza.

In one segment of “Good Morning Mr. Orwell,” a handsome anchor in a New York television studio holds a sardonic philosophical conversation with a female presenter in Paris about the impossibility of modern communication. Their respective studios momentarily lose the broadcast’s live image, and the two talking heads, who apparently know each other intimately, slip into a private conversation about their stilted international romance. In a moment of desperation, the male anchor admits to the long-distance object of his affection, “I don’t care about this show. I don’t care about the avant-garde. All I care about is you.”

Later, Laurie Anderson, her voice modulated into an unnaturally low register, proclaims during a performance, “You are not alone. This is the language of the on-again, off-again future, and it is digital.”

In “Bye Bye Kipling,” a 1986 satellite transmission that linked New York, Seoul, and Tokyo during that year’s Asian Games, Paik brought together avant-rocker Lou Reed and kabuki theater, the composer Philip Glass and a runners’ marathon in Seoul, and the New York graffiti artist Keith Haring, the TV-talk-show host Dick Cavett, and the visionary, Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake. At one point, as Cavett is interviewing Miyake about his relationship to the West, the designer says something resoundingly positive, but his U.S.-based chat-pal cannot hear him. Cavett tells Miyake that, although he has no idea what he just said, he is sure the designer’s remark was wonderful.

These dazzling, dizzy works seem to have unwittingly anticipated the advent of the Internet — in particular, the arrival of livestreams — in a way that feels unflinchingly optimistic. Certainly high technology’s future, routine gathering and selling of its users’ precious personal data or digital surveillance were not subjects that informed the spirit of such works. In fact, Paik chose the title “Good Morning Mr. Orwell” as a rebuttal of the oppressive use of telecommunications that is a central feature of George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 (first published in 1949). When Paik suggested in “Global Groove” that, in the future, we would all have our own television networks, he probably could not foresee the gross hierarchies that would be created by influencer-driven social media, the aggressiveness of cyberbullying, or the use of online communities to facilitate hate-promoting, far-right militancy.

In his work, Paik never proposed regarding electronic screens or digital networks as emblems of morality. Still, he was unfailingly optimistic — and perhaps a bit naïf — about their potential, as was Naisbitt, the best-selling pop soothsayer who, looking back, appeared to have been several steps behind the artist.

III.

The day before I visited Nam June Paik at SFMOMA, my partner underwent an echocardiogram, an ultrasound diagnostic procedure that produces an image of the heart’s movement. When I asked my partner how he felt during the test, he described a sense of uneasiness about seeing an image of his own beating heart projected on a screen.

Ultrasound technology uses sound waves to create rather crude, chalky pictures that exude a rather desolate air. The echocardiogram procedure was accompanied by abstract, atonal noise. My partner described the racket it generated as “metallic and echoey,” with a “tinny whipping sound.”

I thought a lot about his experience as I walked through Paik’s big retrospective. Although the artist did not utilize ultrasound technology to make his art, the meeting of the human body and high technology represented by a modern procedure like an echocardiogram is a theme that felt pertinent as I examined his creations from decades ago.

My partner’s ability to literally look inside his body via an image of his own heart on a screen — that strange phenomenon felt oddly reminiscent as I studied “TV Buddha,” an iconic Paik work from 1974, in which a closed-circuit television camera is trained on a small Buddha statue, whose image is projected on a nearby TV screen. The statue is seated in front of the television set, in the position of a viewer, facing and observing its own projected image. Although “TV Buddha” feels more like a reflection on spirituality than a comment about an object’s physicality, the way this artwork functions reminded me of an echocardiogram insofar as, in Paik’s forceful evocation of self-awareness, the little statue, just like a cardiac patient, is forced by technology to physically and spiritually encounter itself (and contemplate the nature of its existence?).

Following my partner’s recent echocardiogram, his doctors gave him a heart monitor and told him to wear it for a week. That device also reminded me of some of Paik’s experiments. For example, he developed high-tech wearables on multiple occasions, particularly for his frequent collaborator, Charlotte Moorman. An Arkansas native who had studied at the Julliard School in Manhattan, Moorman was a classically trained musician who became a major figure on New York’s avant-garde art scene of the 1960s and 1970s. She wore Paik’s “TV Bra for Living Sculpture” (1969) during traditional cello performances. That strange garment’s two small, cathode-ray-tube TV sets, which covered Moorman’s breasts, could play live television, recorded tapes, or the video feed from a closed-circuit camera.

Paik once observed, “By using TV as bra, […] the most intimate belonging of human being, we will […] stimulate [the viewer’s] phantasy to look for the new, imaginative and humanistic ways of using our technology.”

Paik created “TV Eyeglasses” (1971) for Moorman to wear while playing his “TV Cello” (1971). The strange eyewear often displayed the same images as the hi-tech instrument. For its part, “TV Cello,” a revolutionary work featuring three TV sets stacked inside transparent boxes, is a functional musical instrument. When Moorman played it, Paik’s creation seemed to become one with her body.

IV.

In Love’s Body (1966), the late Norman O. Brown, an American social philosopher and polymath, notes that “to heal” means “to make whole, as in wholesome; to make one again; to unify or reunify: this is Eros in action.” He adds, “Eros is the instinct that makes for union, or unification, and Thanatos, the death instinct, is the instinct that makes for separation, or division.” Here, Eros is that of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, not that of romantic love or an erotic impulse but rather the life force itself.

A few days after seeing the Paik exhibition, my partner learned from his doctors that he has a hole in his heart. Apparently, it has been present since he was born. In order for his damaged heart to heal, through a surgical operation, it will have to be patched. Depending on the exact position of the hole, it will be repaired either through open-heart surgery or by means of a less invasive, outpatient procedure. The latter treatment would involve inserting a catheter into the groin, from where it will be able to reach up into the chest. A skilled surgeon would manipulate the sophisticated device to repair the cavity in the heart.

In Eros in Agony (2012), Byung-Chul Han, the South Korean-born philosopher who is well known for his teaching at the Berlin University of the Arts (and who, like Nam June Paik, left his homeland for Germany when he was a young man), writes about the fate of Eros during the transition from a postindustrial to a digital society. Unlike Freud’s Eros, Han’s also governs love and desire. Han believes Eros is threatened in a society that fetishizes individualism and technologically mediated social interactions.

Han argues that the ability to love requires the negation of the self in order for a person to genuinely discover the “other,” but that, in an increasingly narcissistic culture, the “other” is negated, while the self remains intact.

Thus, as Han suggests, many people now find themselves looking for connection in “the inferno of the same.” (This theory is bolstered, for instance, by evidence of today’s ever-growing social, cultural, and political polarization in the U.S.)

In Paik’s art, informed by the Fluxus ethos of audience participation, the “other” — a viewer, reader, or audience member — is the necessary agent who completes a work of art, an unwitting collaborator who, as Brown might put it, makes it whole.

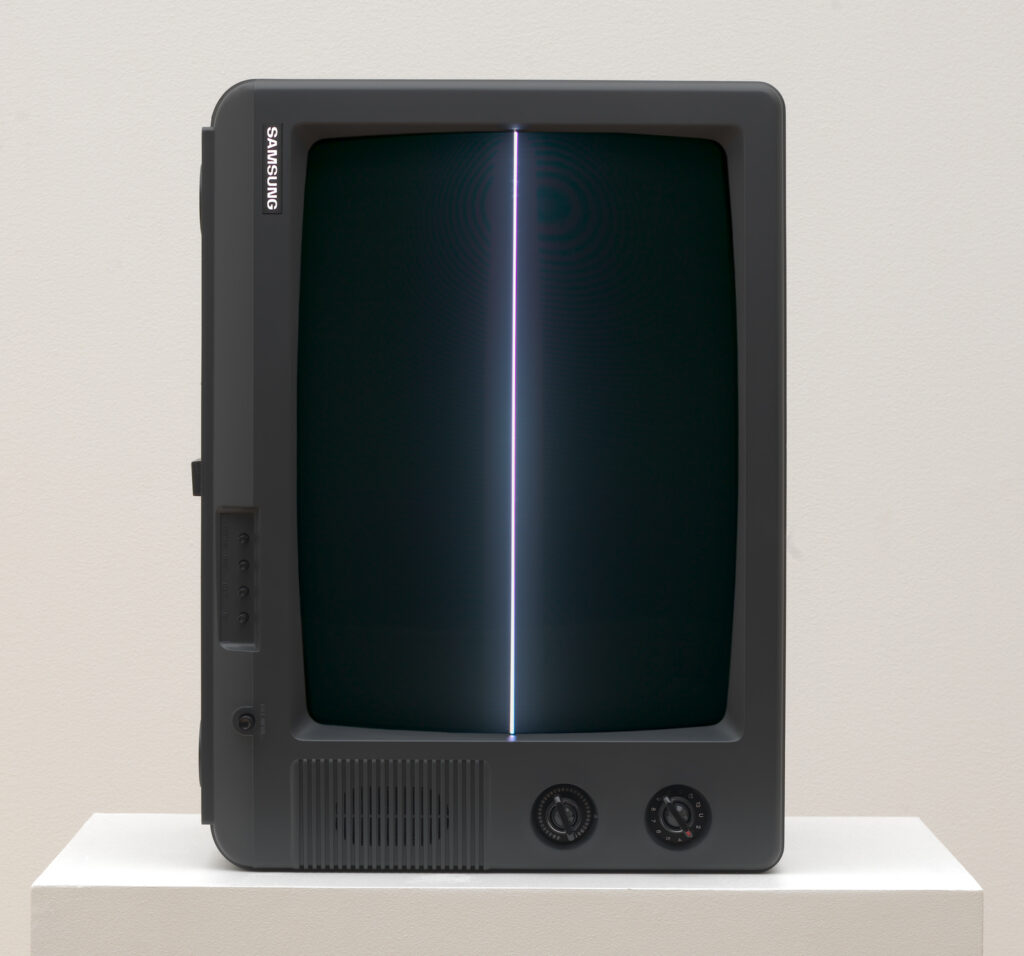

The “other” in Paik’s oeuvre can take multiple forms. It might be the force of chance or some kind of variable, resulting in the kind of unexpected images the artist created, for example, when he employed his “Life Ring 66” (1966), a handheld magnetic coil that dramatically altered the pictures appearing on his analog TV sets. It might be a human- or machine-caused error, as in “Zen for TV” (1963), in which Paik turned a broken TV set into a Duchampian readymade, highlighting the single horizontal line stuck on its damaged screen.

Or Paik’s “other” might be human interaction with technology more broadly, as in “Three Camera Participation/Participation TV” (1969-2001), in which Paik invites viewers to enter a live feed of three CCTV cameras. Without the recognition of the “other” and a sense of active unity with it — or with them, when referring to human interlocutors who enter into dialog with Paik’s engaging art — these works would feel like incomplete, disjointed pieces.

Paik’s work resembles neither a damaged human heart nor the surgical patch with which it may be healed. Instead, his art seems to function in a way that takes disparate elements, joins them together, and shapes them into new wholes. In Paik’s work, Eros, the life force and creator of unity, is always — delightfully and rewardingly — in action.