A LONDON EXHIBITION SHOWCASES THE ART OF A RADICAL, ECO-FEMINIST, EARTH-MOTHER ACTIVIST

Below, as brutjournal’s London-based artist-correspondent Cathy Ward explains, her recent encounter with the work of the Swedish-born artist Monica Sjöö (1938-2005) made a big impact on her. When a well-informed, sensitive art-maker is deeply moved by the thinking and accomplishments of a talented peer, something noteworthy must be going on.

In the spirit of exploring spirits and the spiritual — this month’s big theme — here, Ward describes her reaction to Sjöö’s powerful paintings and explains what the late artist aimed to express through her work.

Monica Sjöö: The time is NOW and it is overdue!

Curated in collaboration with the Feminist Library

June 11 through September 10, 2022

Beaconsfield

22 Newport Street

Vauxhall, London SE11 6AY

England, United Kingdom

Cathy Ward reports:

LONDON— Beaconsfield, an art gallery located in a renovated, Victorian-era building in London’s Lambeth district, across the River Thames from Westminster, is now presenting a remarkable exhibition of the work of the Swedish-born artist Monica Sjöö (1938-2005), who moved to Britain in the late 1950s. The building housing the gallery, which was constructed starting in 1849, was originally the Lambeth Ragged School.

Beaconsfield’s lofty upper gallery room, in which the Sjöö exhibition has been installed, is a space in which young girls were once educated. Certainly, if the artist had lived to see this presentation of her paintings, she would have approved of that historical detail.

In the room in which Sjöö’s works are on display, a sloping floor rises toward its far end, where, in a set-up that resembles an altar, some of her large paintings are hung together, offering the impression that a viewer is looking up, across a horizon, at landscapes and big skies filled with runes and symbolism, and Earth mothers and goddesses. In the room, a high, round window reveals the sky outside. This architectural detail fits in neatly with what is depicted in Sjöö’s paintings, with their cosmic vibes, Neolithic symbolism, primordial goddesses, and discernible spiritual energies.

Sjöö’s art seems to refer to and emerge out of multiple layers of history examined and retold, excavated and represented anew.

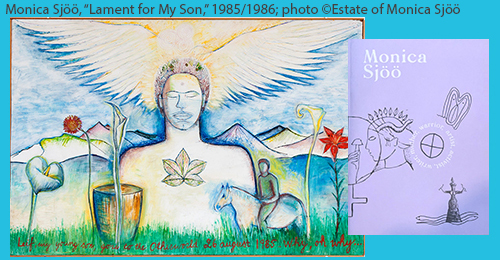

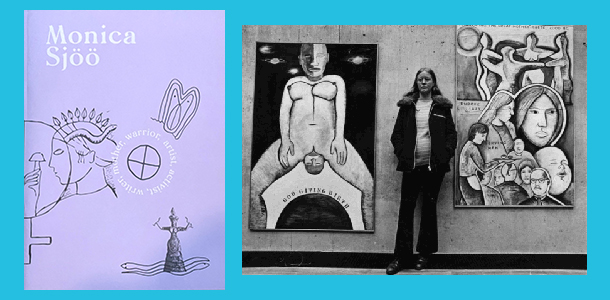

Legion Projects, an artists’ organization based in the United Kingdom, produces exhibitions, publications, and events, which it refers to as “chapters” in an ongoing series of creative undertakings. Earlier this year, it published Monica Sjöö: Artist, Activist, Writer, Mother, Warrior, a limited-edition zine containing reproductions of Sjöö’s paintings as well as texts by Legion Projects, Ruth Lindley, Sue Tate, Rupert White, and the late artist herself.

Jo Eliot, the coordinator and originator of the Monica Sjöö Curatorial Collective, is well informed about the painter-writer-activist’s trajectory. Working with the late artist’s estate, the MSCC advocates for Sjöö’s position as an important feminist artist, writer, and activist. Eliot, a former treasurer of the U.K.-based Feminist Archive and an experienced arts administrator and activist, recalled how she became involved with Sjöö’s multifaceted oeuvre:

She said, “Toivo [Monica’s son], lived in a remote heavily forested valley [in Portugal], at the end of a terrible rutted track in a ramshackle, eco wooden house he had built himself, [where he] was storing some 60 or so of his mother’s huge paintings, and boxes and boxes of sketches, drawings, watercolors, smaller canvases, book covers and writings, banners and cyclostyled political posters […].”

Sjöö died in 2005 in Bristol, a coastal city in southwestern England, where she had lived and worked for many years. After his mother’s death, Toivo and Annie, his partner at that time, packed up and drove all of the deceased artist’s works in a big truck to their home in Portugal.

Looking back, Eliot notes, “I suggested to Toivo that I would try and organize an exhibition [of his mother’s art] in the U.K. It was then that the idea of getting a group of Monica’s admirers and supporters together was born [which would become the MSCC]. Toivo had a heart attack and died. The paintings and archival material are all now in storage in the U.K.”

The current exhibition at Beaconsfield has been organized in collaboration with the Feminist Archive, which has branches in the north of England, at the University of Leeds, and in the southwest of the country, at the University of Bristol. Eliot describes the totality of the Sjöö material as “astonishing.”

Monica Sjöö was born in Härnösand, Sweden in 1938. She was a woman of great conviction and commitment, historically aware, and certainly ahead of her time. In many respects, she was a revolutionary, a prolific artist who, from the mid-1960s, dedicatedly fought against political injustice and ecological decimation by corporations. She was sounding the alarm, alerting the world of a future we are, in fact, experiencing right now. She melded her three prime focuses into a powerful cannon ball of political activism, art, and writing, making no distinction between artworks hung in galleries and her campaigning graphics on banners, posters, and cheap prints.

Eliot points out that Sjöö became “a central figure” in the Goddess Movement, a feminist reaction to male-dominated, organized religion that emerged in the 1970s in North America, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. In that role, Eliot notes, Sjöö educated audiences about “ancient matriarchal cultures” that had existed prior to the rise of “patriarchal religions [that] resulted in […] witch trials and the appalling femicide women [have] endured throughout the centuries.”

Deeply involved in the women’s liberation movement; the Goddess, eco-feminist, and peace movements; and the Bristol Women’s Centre, Sjöö fought for the rights of women and oppressed peoples, taking part in activist campaigns on behalf of women’s access to abortion services and contraception, the interests of single mothers, wages for homemakers, and lesbians. In support of all of these campaigns, Sjöö created artworks to reproduce and distribute to help get their messages out — and to help generate income for organizations acting on behalf of those causes, too.

Sjöö was the main author of Towards a Revolutionary Feminist Art, a mimeographed booklet she produced in 1971 that turned out to be one of the most militant feminist-art manifestos of its time.

Like Eliot, Rupert White is a member of the committee that oversees the activities of the Monica Sjöö Curatorial Collective. A medical doctor, writer, and editor of the online magazine artcornwall.org, which covers the art scene in Cornwall, in southwestern England, White is the author of the book Monica Sjöö: Life and Letters 1958-2005 (Antenna Publications, 2018).

In the Legion Projects zine, White writes: “[Sjöö] moved to Bristol, England in 1959 and married Stevan Trickey in 1960. At [the age of] 26, Monica returned alone to [Sweden,] her mother country[.] engaging in [anti-]Vietnam War protests and expressing her rage against patriarchal society by painting explicit images of enlarged male members, [which] earned her the title […] ‘Sweden’s first pornographic painter.’”

After moving back to the United Kingdom, the artist became friendly with King Mob, the London-based group of Situationists that influenced the thinking of Malcolm McLaren (1946-2010), the creator of the Sex Pistols. Through King Mob, Sjöö was introduced to contacts in the United States, where she later traveled, staying in New York with the social theorist and pioneering environmental activist Murray Bookchin (1921-2006). During her stay in New York, Sjöö also met up with members of Black Mask, a radical artists’ group that planned to shut down the Museum of Modern Art for a day in 1966 but was prevented from doing so when the police preemptively closed that well-known institution.

White notes that Sjöö became involved with Anarchist and Situationist groups of artists and writers in Europe, and referred to herself as “Provies” (or “Provos”). In 1968, she began working on “God Giving Birth,” a painting depicting a standing, non-white woman spreading her legs and straddling the cosmos as she gives birth, the fully visible head of a baby emerging from her vagina. When this painting was exhibited in England in 1970, it was confiscated by the police on the grounds that it was “blasphemous,” and Sjöö was threatened with criminal prosecution.

In her book New age and Armageddon: The Goddess or the Gurus? Towards a Feminist Vision of the Future (London: The Women’s Press, 1992), Sjöö wrote: “While living in Pembrokeshire between 1980 and 1985, I became involved with radical eco-pagans, with [the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament], with actions at Greenham Common, and with the Women for Life on Earth Network. […] Women know that both psychic and physical energies are needed to change the world and ourselves, that we must leap beyond male-perpetuated barriers to become whole spiritual/sexual/political beings in a permanent process of becoming. Re-naming ourselves and the world means that we no longer have to separate the spiritual/cultural and political action. The women at Greenham are a clear example of this. We must, like them, develop […] psychic/intuitive powers and confront daily oppression in concrete and direct action.” (“Greenham Common” refers to the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, a series of protest camps that were set up, starting in 1981, at the now-closed Royal Air Force base at Greenham Common in the county of Berkshire, in southeastern England.)

As for myself, I was introduced to Monica Sjöö’s work in 2001 by Artesian Arts, an artists’ collective based in Edinburgh, Scotland, which was founded by the artist Judith McNicol. Its free-spirited attitude informed Artesian, a magazine that it published, as well as the gallery that it operated. That year, Sjöö’s paintings were exhibited at Artesian Arts.

On that occasion, Artesian published Sjöö’s article “The Artist as Reluctant Sharmanka,” whose title makes use of a Russian word meaning “barrel organ” or “hurdy-gurdy.” In it, the artist wrote, introspectively and in an illuminating way:

“Am I an outsider artist? In struggling to speak for Mother Earth and her spirits, for Gaia’s laws of respect for everything that lives, and for witches and wise women of all ages and times[,] I am most certainly outside the patriarchal status quo, which believes that Earth is simply a human resource to be exploited by ‘mankind.’ I believe we are conscious and alive only because She is. Earth is our great planetary Mother Spirit.”

[…]

“I never desired to be part of the male mainstream […] and art world [,which are] geared to the consumer interests of corporate business, lacking any kind of ecological or political awareness and now cynically celebrating the death of Nature. Although I come from Sweden, originally my images [were] inspired by pilgrimages in the Celtic world as well as in Andalucía in Spain, to Malta, etc. The in-dwelling spirits of the sacred spaces speak to me in visions and dreams. The Goddess — taking many different forms — is again rising within us in these too-dangerous times when our Mother Earth, who gives us life and spirit, is now so threatened. We must fight for her, on life’s behalf.”

“I am an ‘eco-witch,’ an activist, a lifetime feminist. My paintings feel ancient and archaic[,] as if coming from another space and time. I feel [that] past-present-future coexist with us now[,] and that those ancient sisterhoods of many races can communicate with us in the present from other realms. Are my paintings some form of psychic gateways for their re-entry into this world? I am an unwilling Shaman and have been thrown in at the deep end again and again in my life in order, it seems, to gain understanding of other realities.”

Very recently, in London, I spoke with Judith McNicol and asked her to recall her interaction with Sjöö all those years ago.

McNicol told me: “I don’t honestly remember whether I’d got in touch with her directly myself; it must have been [Artesian Arts’] exhibitions manager, Fiona Graham. [At that time, Monica] was already living in Bristol, so we invited her to come and show her work in the gallery [in Edinburhg]. We didn’t fully recognize what a world-changer she was. We regarded her as equal to all [the other] artists we showed. She came and stayed with us, and she had a powerful presence. Although she was not an easy person to get along with, actually, she wouldn’t suffer fools gladly; she was quite opinionated, so we were treading on eggshells, but underneath you knew she was a really likable and thoughtful woman.”

I asked Judith if, during that 2001 visit, Sjöö might somehow have been testing her. She replied, “I think she really appreciated what we had done, taking an interest in her work and what she did. She donated the painting from the exhibition [to Artesian]. I met her daughter-in-law and told her about the painting; she recently wrote to me and asked if we would like to lend it to a museum in Stockholm [for an exhibition that will open there] in May of next year.”

Monica Sjöö was nothing if not original.

In Towards a Revolutionary Feminist Art, she wrote, “Since I consider that the only True Revolution will come about when the silent mass of women finally rise, I will not join a left-wing group but [instead I’ll] work with women in the Women’s Liberation Movement.”