IN ONE OF HIS RECENT BOOKS AND AN EXHIBITION THAT WAS BASED ON IT, THE SWISS ART HISTORIAN AND CURATOR MICHEL THÉVOZ EXAMINED THE MEANINGS OF FRAMES AND FRAMING IN THE WORKS OF ART BRUT CREATORS

by Edward M. Gómez

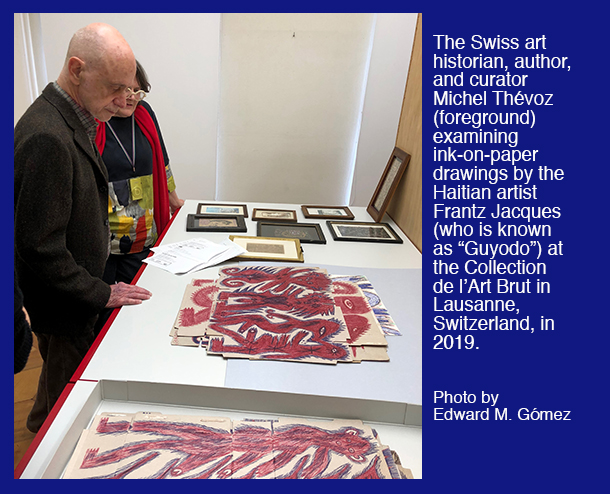

The Swiss art historian, curator, and educator Michel Thévoz is one of Europe’s most original — and respected — thinkers and commentators about art and culture. Thévoz, who was born in 1936 in Lausanne, Switzerland, the elegant, lakeside city that is still his home, was a friend and close collaborator of Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985), the influential French modern artist who, in the 1940s, based on his research and collecting activities in Western Europe, first articulated the aesthetic characteristics that typify art brut (“raw art”) and also gave the phenomenon its name.

Dubuffet donated his personal holdings of the hard-to-classify creations of self-taught artists whom he had discovered living and making art on the margins of mainstream society to the new Collection de l’Art Brut, a museum that opened in Lausanne in 1976. It remains the leading institution in the world whose specialized research, exhibitions, and educational programs focus on such unique and unusual works of art. Thévoz served as the Collection de l’Art Brut’s first director, from the time of its grand opening through 2001. Later, he became a professor of art history and museology at the University of Lausanne.

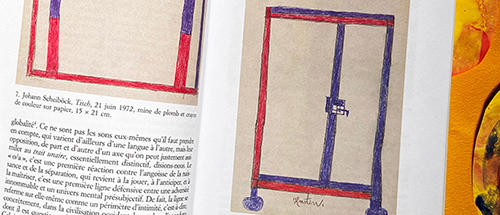

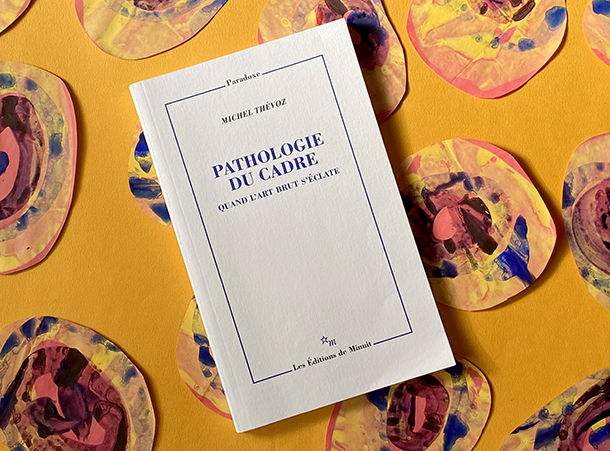

Toward the end of 2020, as the first year of the worldwide coronavirus pandemic was coming to a close, Pathologie du cadre: Quand l’art brut s’éclate (Pathology of the Frame: When Art Brut Explodes), Thévoz’s latest book, was published by Les Éditions de Minuit, one of France’s most distinguished publishers of books in various subject areas that are known for their high literary quality. Over the years, Thévoz has written and published numerous books, including L’Art Brut (Skira, 1975), one of the earliest and now-classic works about the subject it introduced and described.

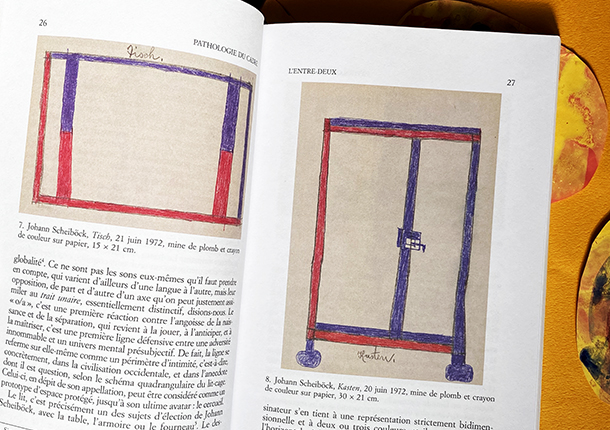

Pathologie du cadre is a compact, 153-page volume that presents many insightful observations about a particular aspect of the art that has long been the focus of Thévoz’s thinking, research, and writing.

His book examines how the idea of the frame, both as a practical, compositional artist’s tool for organizing pictorial space and as a conceptual device for delineating intellectual, social, psychic, or other kinds of boundaries, has been employed by art brut creators and may be discerned in their widely varied creations. In this book, Thévoz also examines more literal examples of frames as objects that demarcate and contain the actual, perceptible borders of works of art and that sometimes become integral elements of their compositions.

Around the time when Pathologie du cadre was published, Thévoz told me that, among his earliest encounters with works of art was his discovery, as a teenager, with those of the Swiss artist Louis Soutter (1871-1942), who made paintings by dipping his fingers in ink or paint. Thévoz observed, recalling his study of Soutter’s works, that, in them, “the frame — that is, the common rectangular format — felt like a form of incarceration.” The human figures Soutter depicted, Thévoz noted, “had to fold themselves into confined, rectangular-shaped pictorial space, and, paradoxically, this constraint led the artist to devise some figurative solutions — deformations [of his subjects’ forms] and extraordinarily inventive anamorphoses.”

In Pathologie du cadre, Thévoz points out that the French word “cadre” (“frame”) has numerous and sometimes related meanings. (Among them is “context”, which brings to mind the somewhat similar word, “framework”, in English.) He writes that the French word “cadre” can be used to refer to that which is “environmental, topological, geometric, architectural, instrumental, hierarchical, educational, judicial, philosophical, aesthetic, etc.”

Given its themes, Pathologie du cadre served as the basis for the development of the exhibition L’Art Brut s’encadre (Art Brut Frames Itself), an exhibition that Thévoz curated and that opened at in December 2020 at the Collection de l’Art Brut. Unfortunately, thanks to pandemic-provoked lockdowns and related, temporary closings of the museum, that insightful exhibition did not receive as much attention as it deserved. (Its run was interrupted several times before it closed in late May 2021.)

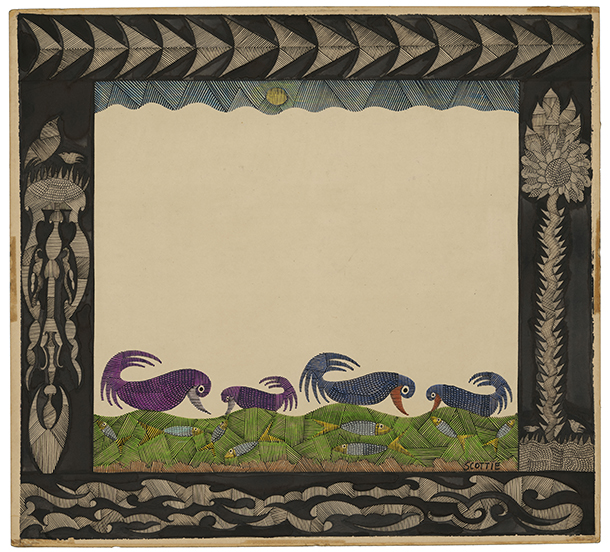

L’Art Brut s’encadre featured works by 40 different artists from the Collection de l’Art Brut’s own holdings, including, among others, Fleury-Joseph Crépin, Magali Herrera, Aleksander Lobanov, Marcomi, Scottie Wilson, Josef Wittlich, and Adolf Wölfli. Instead of a coventional catalog, Thévoz’s book served as the exhibition’s accompanying publication.

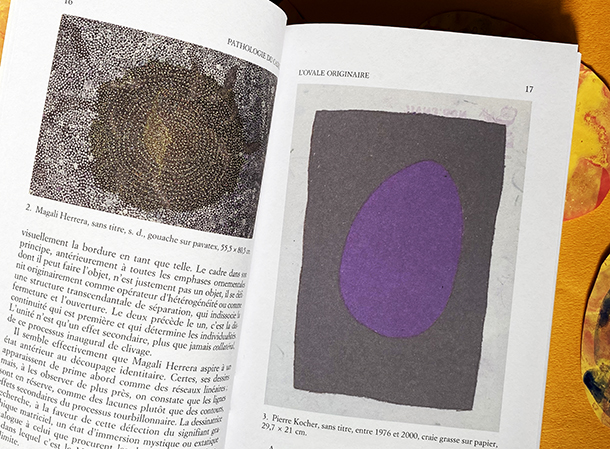

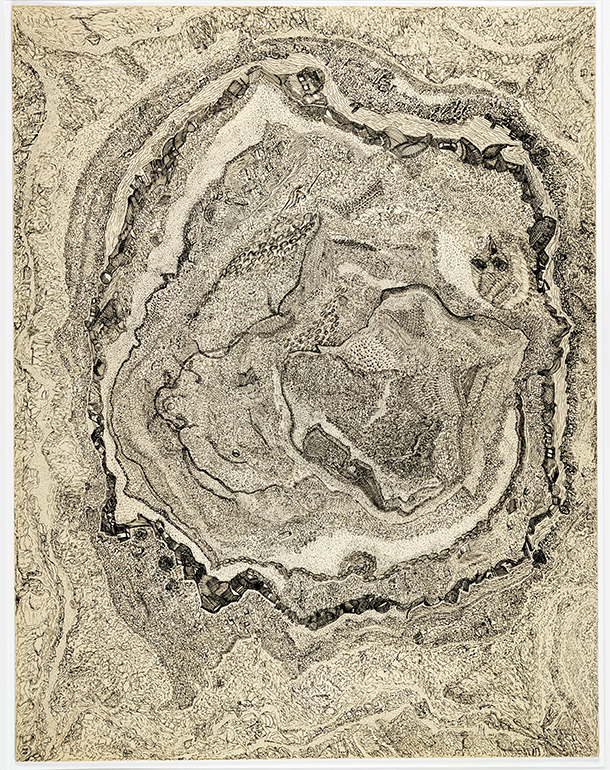

Like Thévoz’s little treatise, the museum’s presentation examined how the concept of the frame and of framing ideas or visual content may find expresson in different ways in the works of various self-taught artists. For example, both the book and the exhibition called attention to the way in which, in the Uruguyan Herrera’s flowing, abstract, ink-on-paper drawings, various elements appear to gather and contain themselves within sections of her compositions, which seem to grow or emerge organically.

Thévoz’s thinking about the use of the frame as an art-making device also takes into consideration Wölfli’s richly detailed drawings in pencil and coloured pencil on paper. In them, the Swiss art brut creator used decoratively patterned borders to mark off sections of his pictorial space. Often these clearly designated areas within his compositions function as the holders of and staging areas for illustrated, narrative vignettes.

The German-born artist Josef Wittlich incorporated boldly drawn graphic elements into his pictures. They function as de facto frames. Crépin, who sometimes made his own physical frames using stained-wood molding, also framed the subject matter he depicted within his images. In Pathologie du cadre, Thévoz cites some of the painted-paper works of the Swiss artist Hans Krüsi, in which images of human figures or cows appear in compositions whose formats bring to mind Warholian grids or the regular repetition of motifs that is a hallmark of many works of modern art.

In both his book and in the Lausanne museum’s exhibition, Thévoz noted that, sometimes, artists may employ methods of framing the content of their images even as they defy the conceptual or spatial restrictions they impose. The Swiss artist Aloïse Corbaz, for example, routinely packed her fantasy images with human figures whose bodies function as frames for assorted, painted motifs, and if or when she felt compelled to extend a composition beyond the confining borders of the paper on which she was painting, she simply stitched together additional pieces of paper to create ever-longer, scroll-like picture-making space.

Among the various categories of frame-employing artworks Thévoz identifies is one he calls “His Majesty, Me.” Works to which that descriptive label apply include self-portraits made by such artists as Aleksander Pavlovitch Lobanov, in which elaborately drawn and decorated borders function both as integral elements of their compositions and as conveyors of essential narrative information.

In reflecting upon the themes of the frame and framing, and in

examining a broad selection of relevant works produced by assorted art brut creators, in his writing and exhibition-making, Thévoz has placed relatively more emphasis on what such artists have achieved formally and technically in their art than on the details of their respective life stories. This more formalist appreciation of their accomplishments, which is well informed by Thévoz’s broad understanding of art and cultural history, is refreshing in a field that has long put considerable emphasis on artists’ biographies.

Regarding the themes of frames and framing, when I interviewed Thévoz at the time Pathologie du cadre was published, he noted, “Each art brut creator grapples with the sacred rectangular border, which is something trained artists take for granted, but which, for art brut makers, represents a challenge but also, as a result, a jumping-off point for creative invention.”

Although Pathologie du cadre has not yet been translated into English, it’s a book whose underlying research and superbly focused, illuminating observations and arguments are certainly worthy of the attention of a wide audience of art lovers, curators, students, and artists.