THE VIBRANT WORK OF A LITTLE-KNOWN, SELF-TAUGHT ARTIST FROM ILLINOIS IS EMERGING — BOLD, INTENSE, AND PACKED WITH CREATIVE ENERGY

by Edward M. Gómez

Sometimes, it seems, an artist’s creative vision may be bigger and more potent than anything the pictorial space of a painting or drawing can contain, or that conventional art-making materials and genres might allow him or her to express.

In the case of the self-taught artist Maurice Sullins (1910-1995), who only started producing art at the age of 60, both a sense of exuberance about making pictures and an unbridled creative urge appear to be as much the subjects of his large, diverse body of work as any of the mountains, trees, semi-abstract human figures, and stylized Eiffel Towers his boldly painted canvases depict.

Sullins, whose ancestors were French, lived in Joliet, Illinois, a city located about 30 miles southwest of Chicago, where he worked as a waxer and detailer of airplanes at a local airport. Apparently, on his own, mainly by looking at books, Sullins learned about a wide range of modern-art styles and approaches to painting, all of which he assimilated, interpreted in his own ways, and then poured into his work.

He took on the imposing nom d’artiste “Maurice LeGrand LeSueur Sullins” and referred to himself as “Maurice LeGrand,” gestures that, in retrospect, were very much in keeping with modernism’s celebration of the heroic, ruggedly individualistic author-creator as an unstoppable productive force. Like many more well-known, canonical modern artists, Sullins created his own artist’s persona — and in presenting his artistic accomplishments to the world, boldly dared to live it, too.

Sullins produced roughly 1200 paintings during the period from 1970 through 1986. He stopped making art following the death of his wife, at which time he turned his attention to trying to publicize and promote his work. In January 1987, a feature article in the Chicago Tribune introduced his paintings and life story to the public. “At an age when many people grab their pension funds and run, he set out to be a painter with the joyous fever of the obsessed,” wrote the article’s author, Mary T. Schmich.

In her report, she noted, too, that Sullins had picked up the few French words he knew from dictionaries and cookbooks, that he slept only a few hours each night, and that his house was filled to bursting with his stored paintings, reference materials (like more than 1000 copies of the magazine National Geographic), and an in-progress assemblage sculpture made of hundreds of stuck-together trinkets, from badminton birdies and candle holders to old shoelaces.

The discovery of Sullins’ art and the emergence of his unusual story began attracting the attention of some collectors and dealers, culminating in the retrospective exhibition Maurice LeGrand LeSueur Sullins: Paintings 1970-1986, which was organized by the Illinois State Museum and opened in January 1988. It was presented at three of that institution’s venues, including the State of Illinois Art Gallery in Chicago.

After the artist died in 1995, his family placed his artworks in storage, where they remained, out of public view and not actively promoted, for more than two decades. However, in 2017, the Chicago-based Hana Pietri Gallery became the official representative of the late artist’s estate and, that same year, mounted its first exhibition of a selection of his long-forgotten or still widely unknown paintings. Recently, in early March, Tiphanie Babinet, who runs the gallery, showed a selection of Sullins’ paintings at the 2022 Outsider Art Fair in New York.

There, brutjournal spoke with her about the artist’s life story and his art-making career, such as it was; it was situated decidedly on the margins of mainstream society and cultural activity. While mulling over the theme of this month’s issue of the magazine in mind — how artists have been inspired by, have responded to, or have depicted the forces of nature in their work — Babinet recalled how she became involved with Sullins’ large, impressive, well-preserved oeuvre.

She told brutjournal: “I first saw a selection of Maurice’s paintings in 2016, at the home of his son, Victor. I was introduced to the family and to the collection by Jerry Adelmann, JoAnn Seagren, and Scott Lang. Adelmann met Maurice in 1987 and purchased paintings directly from him following that very first article that was published in the Chicago Tribune. Jerry was instrumental in organizing the Illinois State Museum exhibition and has been a great resource.”

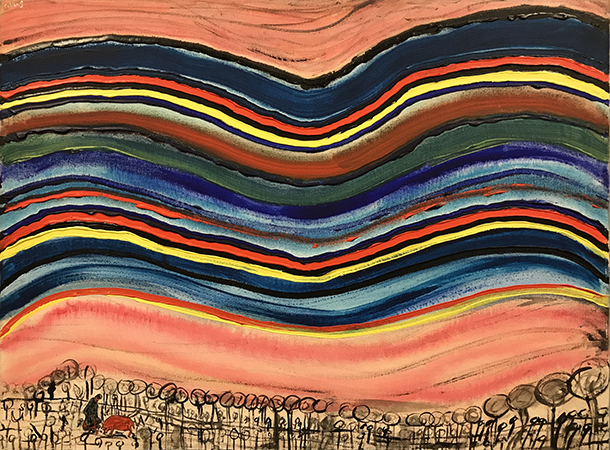

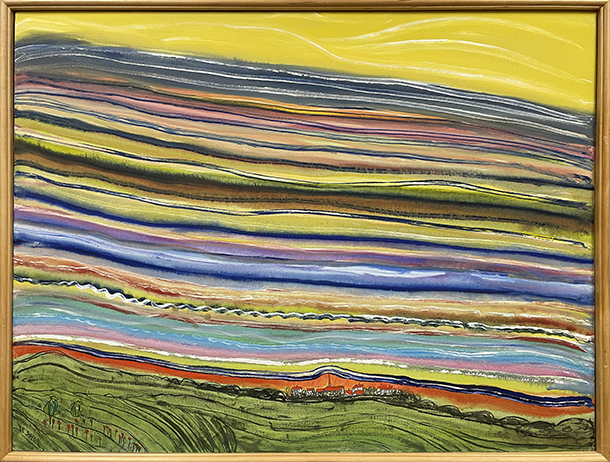

With their dramatically dynamic, expansive skies filled with clouds and lightning that make Van Gogh’s glowing stars look like tired pinwheels; their fantasy-abstract landscapes that fuse sky and earth in bands of pulsating color; and their interior scenes that effortlessly appropriate and rework a Cubist draftsman’s line and space-shifting perspective, Sullins’ paintings make a strong impact. How did Babinet respond when she first saw them?

She recalled, “My reaction was visceral. The quality of Sullins’ compositions, his incredible use of color, his unusual techniques and subject matter, and his sense of humor struck me, as well as the statement he [seemed to be making] about continuing the work of the great masters [through his own work].”

Babinet added that she was intrigued by the ways in which, in his own paintings, Sullins “transformed and construed famous, recognizable motifs and figures [from well-known works of art] into his own language.” As she sees it, in his own art, “Sullins did what the masters often had done — he drew inspiration from the unschooled.”

It’s true that, in the past, certain individual or groups of modern artists were inspired by the creations of folk artists and others who were not academically trained. With this historical link in mind, recall, for example, the still-young Museum of Modern Art’s presentation in New York, in 1932-33, of the exhibition American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750–1900.

Babinet’s observation packs a double whammy of art-historical affinities, for Sullins was an untrained artist who was inspired by some of the giants of modernism who, in turn, had been interested in and inspired by the creations of self-taught art-makers like “LeGrand Sullins” himself.

In her research about Mullins’ life and working methods, Babinet found out that the artist had kept some journals, in which he had written notes about his art and ideas. About this valuable historical material, she said, “They [serve as] an extraordinary window into his state of mind and include vital, detailed remarks about the meaning of each painting as well as free-flowing thoughts describing his invented techniques, references to other artists, the time he spent on each painting, etc. His journal entries often help to date his paintings. Sullins also wrote comments on many of the works he created on canvas panels.”

As Babinet and her gallery continue exploring the scope and thematic diversity of Sullins’ work and bring it to market in well-curated exhibitions, private collectors and institutions alike stand to benefit from the quality of their research and respectful custodianship of the artist’s legacy. Such thoughtful handling of any artist’s oeuvre is significant whether he or she is deceased or not; for the work of a self-taught art creator who was unknown in his lifetime but whose achievements merit serious critical attention and appreciation, it can be all the more meaningful.

Sullins wrote notes about his paintings on their back sides. On the verso of “Great Dark Cloud Over Tahiti Nice,” one of his earliest works, from June 1970, he described it joyously, noting, “This painting is easily the most colorful one in existence!”

It turns out that the artist’s enthusiasm for making art and the creative spirit that fueled his intense activity over a relatively short period of time were forces of nature in their own right.

The works he left behind, which are now ours to enjoy, exude their indomitable spirit.

Resources

Website page of Hana Pietri Gallery, Chicago, focusing on the artist Maurice Sullins; click here.

On this page, the catalog that accompanied the Illinois State Museum’s Sullins exhibition of 1988-89 and early newspaper articles about the artist may be found and viewed, in their entirety, as they first appeared in printed, published form.