THREE EXHIBITIONS SHOWCASE THE AMERICAN ARTIST’S PIONEERING CONTRIBUTIONS TO FEMINIST AND PERFORMANCE ART

by Edward M. Gómez

Martha Wilson is well known internationally as the founding director of Franklin Furnace Archive, one of the pioneering, so-called alternative-space art institutions that emerged in New York in the 1970s to promote performance art and avant-garde art forms that were new and fresh, and for which there were no familiar labels.

Wilson is also an accomplished performance and visual artist in her own right. Although her work had been known among a certain community of contemporary artists, over the past decade or so, thanks to several high-profile traveling or gallery exhibitions, the scope and impact of her art and ideas have become better known to broader audiences and to the larger, international art establishment.

As the Zeitgeist’s pulse-takers like to say, right now, Martha Wilson is having a moment.

Starting this month, Wilson’s work will be showcased in Martha Wilson à Halifax, 1972-1974 (Martha Wilson in Halifax, 1972-1974), a solo exhibition at France’s National Museum of Modern Art, which is housed in the Pompidou Center, in Paris. Opening on October 20, it will run through January 31, 2022. This survey will be accompanied by a series of in-person talks featuring the artist and other special events; see “Resources,” below, for more information.

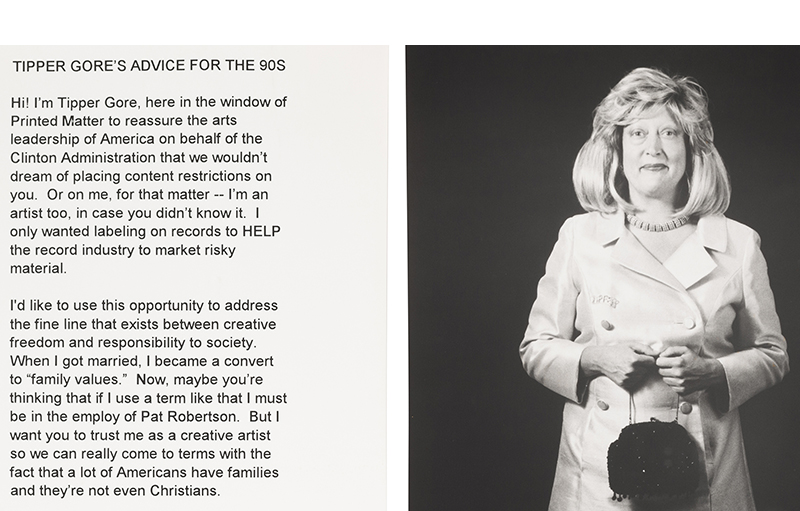

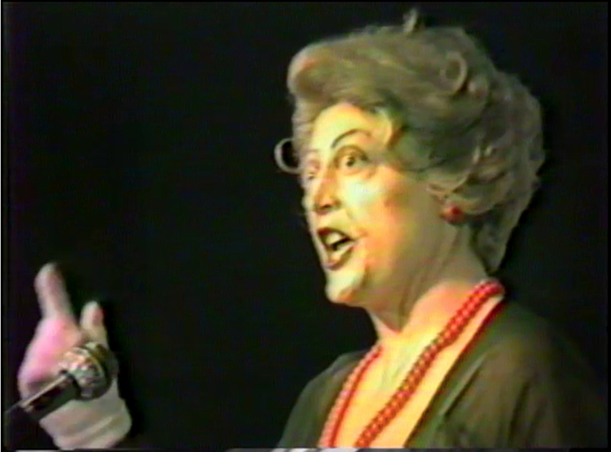

Also in Paris, mfc-michèle didier, a contemporary-art gallery, will present Political Performances and Carte Blanche to Martha Wilson (October 16, 2021 through January 8, 2022), featuring documentation of the artist’s performance-art impersonations of the American first ladies Nancy Reagan and Barbara Bush, and of Tipper Gore, the ex-wife of former U.S. Vice President Al Gore. During their husbands’ periods in office, all of those politicians’ wives became involved in various aspects of the contemporary “culture wars” in the United States. Through her performances, Wilson took on their conservative positions using costume and disarming parody.

At mfc-michèle didier, in the role of guest curator, Wilson will also present a selection of works by fellow artists whose ideas, critiques, and attitudes have informed her own and, over the years, have shared formal and thematic dialogs with her own oeuvre. Among the other artists whose works will be included in this “carte blanche” offering: Vito Acconci, Lynda Benglis, Judith Bernstein, Ilona Granet, Barbara Kruger, Suzy Lake, Howardena Pindell, and Carolee Schneemann.

On the occasion of its Wilson exhibition, mfc-michèle didier will publish Journals, excerpts from the artist’s personal writings from the period from 1965 to 1983. In them, her observations about the life and work of an artist who was also developing a vibrant cultural institution overlap with her thoughts about the social-political and cultural climates in the U.S. during the AIDS crisis and about the rise of an aggressive conservative movement whose dubious leader, Ronald Reagan, paved the way for the politics of mendacity, privilege, and institutionalized corruption that would later characterize the Republican Party, culminating in the rise of its neo-fascist cult of Trump.

In a recent interview, Wilson told brutjournal: “My journals were written between 1965, when I graduated from George School, a Quaker high school in Newtown, Pennsylvania, and 1983, after DISBAND, an all-girl punk band of women artists who couldn’t play any instruments, in which I had taken part, had disbanded — in 1982 — and I started performing as ‘Alexander M. Plague,’ and then as Nancy Reagan, Barbara Bush, Tipper Gore, and Donald Trump.”

Finally, through November 15, the newly opened Bourse de Commerce/Pinault Collection in Paris, which is housed in a domed, former stock-exchange building that has been renovated by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando, is presenting Journiac, Lawler, Levine, Prince, Sherman, Wilson. This group exhibition features works by artists who have used staged photographic images as tools with which to examine and critique social stereotypes and different ways in which personal identity may be projected and perceived.

From her home in Brooklyn, Martha Wilson has traveled a long way to reach Paris.

Wilson told us: “The exhibition at the Pompidou Center includes all the work I created between 1971 and 1974, while living in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. In 1969, at the height of the Vietnam War, I graduated from Wilmington College, a small school that was founded by Quakers in 1870. I was a Quaker, and my boyfriend didn’t want to get drafted, so we decided to move to Canada. Why Halifax? Our painting teacher, Gerry Ferguson, had been hired away from Wilmington to teach at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. I applied for and won a fellowship in English literature to Dalhousie University, which was located across the street from NSCAD, where my boyfriend had enrolled in the MFA printmaking program. We took all of these developments as a sign from above.”

Looking back at the start of her art-making career, Wilson recalled: “After a year or so in Halifax, I found that the kids at the art college were way cooler than the ones in the English department at Dalhousie, so I hung out at NSCAD and started making my own art. It was text-based, because I was an English major, and conceptual art was the art form of the moment.” Emerging conceptual artists, such as Vito Acconci and Lawence Weiner, who would become influential in the 1970s, visited the art school to present their ideas and their work. Their message, Wilson was glad to hear, was that “text and image were equal in value!”

Wilson told Ferguson, her former painting teacher from Wilmington College, who was now teaching at NSCAD, that she wanted to become an artist. She remembers that he told her: “Women don’t make it in the art world! But if you’re serious, you’ll make black-and-white art.”

In response, Wilson recalled, “This made me so mad that I walked across the street, bought a roll of color film, and started dressing in drag to find out what it was like to be a man trying to look like a woman. I used makeup to paint myself as beautiful and as ugly.”

Wilson created the photo series “Posturing Drag” (1972), in which she dressed up as a man impersonating a woman, a butch lesbian, and a middle-aged woman. In another series, “A Portfolio of Models” (1974), she produced character portraits in which she photographed herself in the roles of “Goddess,” “Housewife,” “Working Girl,” “Professional,” “Earth Mother,” and “Lesbian.” “These are the models society holds out to me,” she wrote in their accompanying, typewritten, explanatory note, adding, “At one time or another, I have tried them all on for size, and none has fit.”

In another work, “Breast Forms Permutated” (1972), she presented a grid of nine photos of female chests accompanied by notes describing the look and character (“conical,” “spherical,” “pendulous”) of the pairs of breasts they depicted, with a “perfect set” placed in the middle of her composition.

Wilson noted that, around the time she was creating such works, “The environment at the art college was openly hostile to women, and there was no feminist community in which to find support, but one day, the American art historian, critic, and curator Lucy R. Lippard visited NSCAD, looked at my work, and told me that I was indeed an artist, and that there were other women in Europe and North America who, like myself, were exploring feminist concerns. Lucy also informed me that she would include my work in c. 7500, an exhibition of feminist art that she was organizing. It opened at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, California, in 1973, and then traveled to other venues in the United States.”

The women artists whose thinking and activities Lippard had been closely monitoring when she first met Wilson included, among others, Judy Chicago, Eleanor Antin, Suzy Lake, and Martha Rosler. Like Wilson, they all had been examining women’s traditional social roles and their portrayals in art and the media, as well as the nature of “women’s work.” (Years later, a younger artist, Cindy Sherman, would mix postmodern irony with the spirit of those earlier feminist investigations in her “Untitled Film Stills” (1977-1980) series, in which she would photograph herself in the poses of actresses in familiar, movie-genre roles.)

After Wilson’s Canada sojourn, she moved back alone to the U.S. and settled in New York, where, in the mid-1970s, she founded the Franklin Furnace Archive. Through the late 1990s, overseeing and seeking funding for the arts center’s programs occupied much of her time. The institution itself was housed in a two-level loft space in an old building on Franklin Street, in the TriBeCa district of downtown Manhattan. There, it mounted exhibitions, presented performance art and other events, and built up an extensive collection of artists’ books, performance-art documentation, and other works that Wilson and her colleagues described as “time-based art or ephemeral in nature.”

During the “culture wars” of the 1990s, Franklin Furnace was often in the news, for it served as a showcase for numerous artists who addressed controversial subjects — sex and sexuality, war, censorship — and also as a platform for those who expressed progressive ideas about art, culture, society, and politics.

In early 1997, after closing its physical space, Franklin Furnace launched a website and became an Internet-based presenter of performance art and online archive of material documenting many of the events it had presented in the past. Today, it still operates a grants-for-artists program. In recent years, the organization has become an independently functioning entity in association with Pratt Institute. Its offices are located on Pratt’s Brooklyn campus.

The art dealer Michèle Didier, whose gallery has branches in Paris and Brussels, and sponsors an active publishing program, first met Wilson in the late 1980s, when she visited Franklin Furnace. In collaboration with P.P.O.W., the New York gallery that represents Wilson in the U.S., Didier showed the artist’s seminal, early works in the Unlimited section of the Art Basel fair in Switzerland in 2019. Later, the National Museum of Modern Art at the Pompidou Center acquired one of those works.

In a recent e-mail interview, describing the social-cultural context in which Wilson’s oeuvre is becoming known in France and Europe, Didier told brutjournal: “Feminism has not exerted itself in the same way in Europe as it has in the U.S. In 2001, I organized an exhibition of the work of [the French artist] Annette Messager and [the American] Lynda Benglis in order, in fact, to be able to make clear, to some degree, two forms of feminism expressed by two women artists of almost the same generation.” Through that exhibition, Didier noticed certain differences in those two artists’ respective ways of thinking and in their art-making approaches.

She explained: “Feminist artists in Europe and especially in France are not engaged in the same way [as their American counterparts], notably in political or activist ways. In France, many fewer women artists have become well known and those who have become known have put forth their work in ways that are much more individualistic than in the U.S., where the tendency to act collectively was evident much earlier on.”

About the two-part exhibition her gallery in Paris is presenting, Didier noted: “We’re emphasizing Martha’s performative work and its relationship with parody and pantomime.” The concurrent Pompidou Center exhibition, she added, “will allow the seminal aspects of Wilson’s work, which, as I see it, had few equivalents in its time, to be highlighted.”

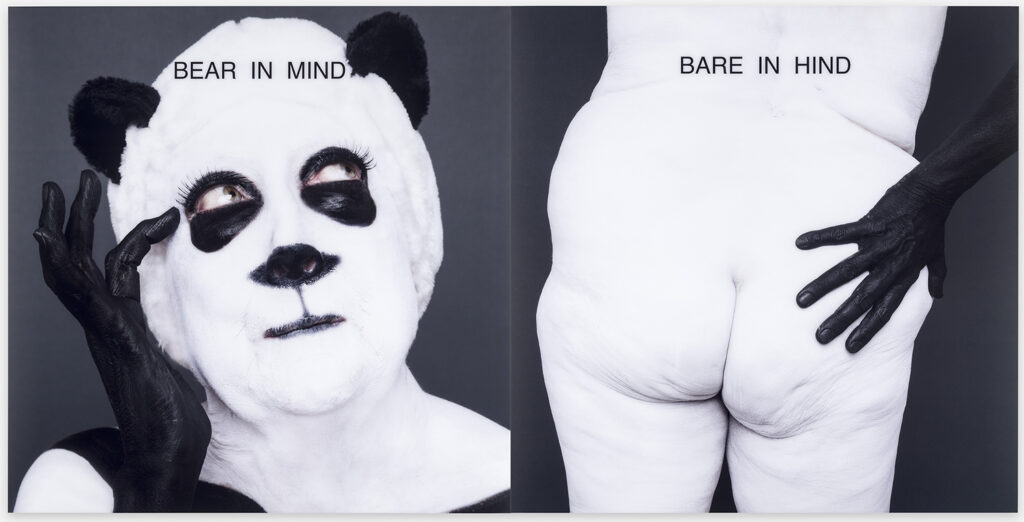

In recent years, Wilson has combined staged photos of herself in various costumes, brief texts, references to art history, and self-deprecating humor in image-based works that have examined society’s attitudes regarding aging. Her occasional performance-art turns as a bumbling Donald Trump, with a bright-orange wig and dangling necktie, have called attention to the deceiving banality of a comic-book character whose sweeping destructiveness has become an ominous force in the U.S. and beyond.

Wilson said: “In my current work, I’m exploring what it’s like to be an old lady in such pieces as ‘The Legs Are the Last to Go,’ ‘New Wrinkles on the Subject,’ and ‘Growing Old.’ After I let my hair grow out gray, so that I could appear as Bill Clinton in a piece called ‘Name = Fate,’ one time I was walking along in Brooklyn, and someone bumped into me as though I weren’t even there. Then it happened again! So I made a piece titled ‘Invisible’ about how women of a certain age just aren’t seen anymore.”

Now, though, both Wilson and her art of provocative images and ideas have become very visible, attracting the kind of serious critical attention the artist never anticipated when she first began examining, in a very natural way, emerging out of her life’s own experiences, the multifaceted aspects of the female self.

She said: “In 2013, the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design invited me to return to Halifax to receive an honorary doctorate in the fine arts. A woman who is now on the staff of the school told me, ‘You were an example to us!’ — and my immediate thought was, ‘Why didn’t you tell me earlier?!’”

Resources

Website page of the National Museum of Modern Art at the Pompidou Center, Paris, describing the exhibition Martha Wilson à Halifax, 1972-1974 (Martha Wilson in Halifax, 1972-1974) and its related programming:

in English

https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/program/calendar/event/biaXcZh

in French

https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fr/programme/agenda/evenement/biaXcZh

Website page of the gallery mfc-michèle didier, Paris, describing the exhibition Political Performances and Carte blanche to Martha Wilson

Website page of the Bourse de Commerce/Pinault Collection, Paris, describing the exhibition Journiac, Lawler, Levine, Prince, Sherman, Wilson

https://www.pinaultcollection.com/en/boursedecommerce/journiac-wilson-levine-sherman-prince-lawler

Website of Franklin Furnace Archive, New York

http://www.franklinfurnace.org/