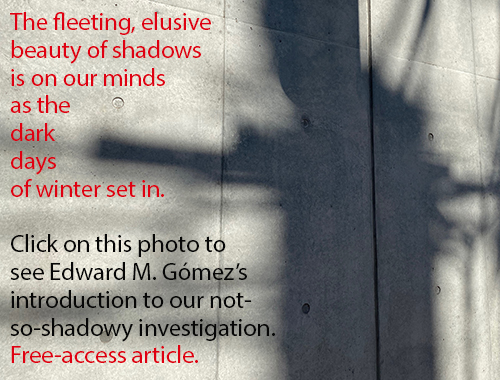

SCULPTURAL BUT INTANGIBLE. SHAPELY BUT IMPERMANENT. SHADOWS ARE THE JEWELS OF LIGHT’S JOYOUS SENSE OF PLAY — WITH ITSELF

by Edward M. Gómez

If shadows were to sit down together and compose a manifesto, part of it might declare, “Pay attention to us! We’re everywhere. Our delicate, fleeting beauty is not to be taken for granted!”

Ask any kitty cat, that innately capable representative of a species that long ago mastered the art of creative, determined lounging: Just what is it about watching a shadow creep slowly across a wall as the light of a lazy afternoon fades and changes its temperament that is so inescapably enchanting?

Certainly the ancient Indians and Chinese were on to something when they created shadow puppetry, an entertainment and storytelling method that is at once so simple and deeply expressive, anyone can instantly grasp its magic. Also known as “shadow play,” the technique consists of placing figures cut out of sheets of metal, paper, wood, or fabric between a light source and some kind of screen so that their shadows will be projected on that display surface, allowing viewers on the other side to delight in the movement of those hand-manipulated shapes.

Is there a child anywhere who, with his or her own little hands, has not projected shadow puppets — bunnies, dinosaurs, monsters! — on a wall using a flashlight, candle, or, nowadays, maybe the screen or built-in flashlight of a mobile phone?

In 1933, the Japanese writer Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (1886-1965) released “In’ei raisan”(“In Praise of Shadows”), an essay about traditional Japanese aesthetics that has remained one of the most lucid and evocative discussions of its subject ever written.

Tanizaki, whose novels, such as “Tade kuu mushi”(“Some Prefer Nettles,” 1929) and “Sasameyuki”(“The Makioka Sisters,” 1943-48), wistfully reflect a sense of early-20th-century Japan’s transformation in the face of Western modernist influences, used “In Praise of Shadows” to capture the spirit and, sometimes explicitly, to explain the fundamental principles of an aesthetic outlook that had informed almost every aspect of Japanese life as he had known it.

[Editor’s note: A downloadable .pdf containing the complete English version of Tanizaki’s essay can be found here. This is the translation by Thomas J. Harper and Edward Seidensticker that was published in 1977 by Leete’s Island Books. Our citations come from this version.]

In his gently flowing text, instead of employing opaque academic jargon, Tanizaki offers example after example of the many ways in which shadows, from those cast by a traditional Japanese house’s overhanging eaves to those suggested by the enticing darkness of soup served in an old lacquer bowl literally influence how the Japanese regard objects, the built environment, and their physical presence in the world at large.

In “In Praise of Shadows,” Tanizaki writes, “Every time I am shown to an old, dimly lit, and, I would add, impeccably clean toilet in a Nara or Kyoto temple, I am impressed with the singular virtues of Japanese architecture. The parlor may have its charms, but the Japanese toilet truly is a place of spiritual repose. […] No words can describe that sensation as one sits in the dim light, basking in the faint glow reflected from the shōji, lost in meditation or gazing out at the garden.”

Elsewhere, commenting on the character of the roofs of Western-style buildings, he observes that they are designed “less to keep off the sun than to keep off the wind and the dew,” and that “even from without[,] it is apparent that they are built to create as few shadows as possible and to expose the interior to as much light as possible.”

He adds that, by contrast, the quality the Japanese call “beauty” is one “that must always grow from the realities of life, and our ancestors, forced to live in dark rooms, presently came to discover beauty in shadows [and] ultimately to guide shadows toward beauty’s ends.”

“Diànyǐng” (电影) the Mandarin Chinese word for “movie” or “film,” literally means “electric shadow.”

It’s hard to imagine a more poetic way of referring to the allure of projected moving images on a visible surface that is the imagination-seizing spectacle of cinema.

The modes of delivery of the treasure troves of motion-picture entertainment and reference material that are easily available nowadays, via the Internet, on all sorts of digital devices, have almost killed off the cinema-going experience, but just the thought of movies sharing a lineage, however allusive or conceptual, with ancient shadow plays, still wrapped in the mystery and magic of the dance of fleeting, flickering, untameable light, makes us want to catch a sunbeam, hold up our own silly, mischief-making fingers, and throw some funny-spooky shapes against a wall.

Our praise of shadows begins with an act of seduction. Wrap us in the embrace of their soulful, transient, strangely radiant light.