THE SWISS ART HISTORIAN EXPLORES ARTISTS’ REAL AND IMAGINARY WORDS

Lucienne Peiry is one of the foremost experts in the world in the art brut field, with many years of experience and many notable achievements to her credit as a researcher and author, exhibition curator, and participant in scholarly conferences. In the past, for ten years, she served as the director of the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland. The first museum of its kind in the world, it was founded in the 1970s by the French modern artist Jean Dubuffet, the best known and most influential of the pioneering researchers and collectors of art brut. It was Dubuffet who gave the phenomenon of art brut (“raw art,” in French) its name.

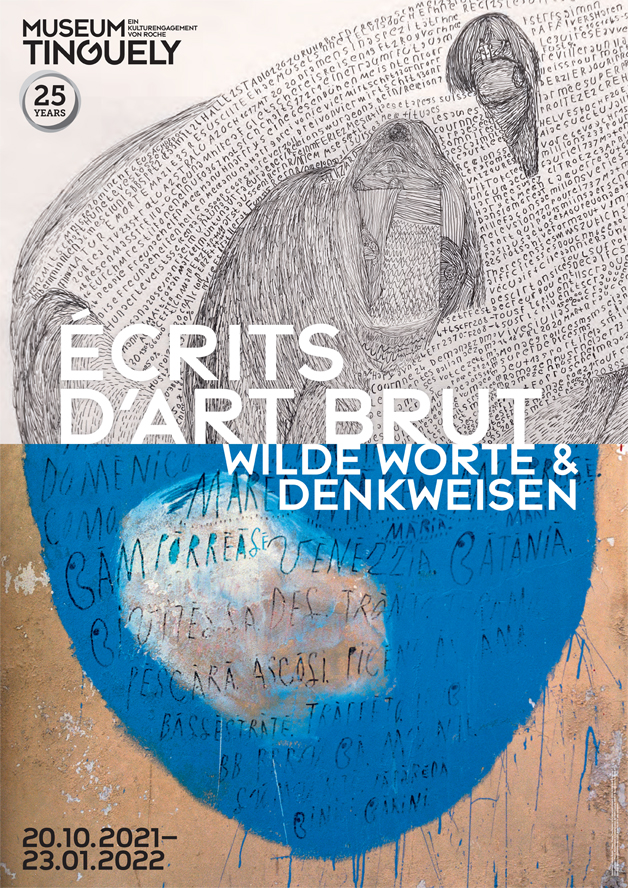

Late last year, at the height of the worldwide pandemic, Peiry’s latest book, Écrits d’Art Brut: Graphomanes Extravagants (Art Brut Writings: Extravagant Graphomaniacs) was published in France by Éditions du Seuil.

In this well-illustrated, encyclopedic book, Peiry examines the work, ideas, and art-making methods of 30 visionary autodidacts in the related art brut and outsider art fields, all of whom routinely and vividly incorporated writing into their compositions, integrating it with their visual imagery.

Some of them, such as the Swiss creator Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930) or the Italian Carlo Zinelli (1916-1974), are well known to aficionados of this kind of art. Some of Peiry’s other subjects, including, among others, Emma Hauck, Laure Piegon, Agnes Richter, and Jean Crampilh (who was known as “Jeannot”), might be less familiar to many readers.

Now, brutjournal is excited to publish, exclusively, a translation into English of excerpts from Écrits d’Art Brut: Graphomanes Extravagants. These extracts are taken from the book’s chapters on the artists Noviada Abgkasapura, Arthur Bispo do Rosario, Marie Lieb, John B. Murray (commonly known as “J.B. Murray”), Giovanni Battista Podestà, and Charles Steffen. Peiry’s observations about these varied creators’ respective approaches to producing their art, their creative impulses, and their distinctive oeuvres are fresh and revealing.

Her book serves as the basis for the new exhibition Écrits d’Art Brut: Wilde Worte und Denkweisen (Art Brut Writings: Wild Expression and Thought), which will open at the Museum Tinguely, in Basel, Switzerland, on October 20, 2021, and remain on view through January 23, 2022. Peiry has curated this presentation of works by many of the artists who are cited in her book; Sarah Nedir designed the exhibition.

Both as a book and, now, as an exhibition, Écrits d’Art Brut shines a light on the wide range of letters, erotic or diaristic notes, utopian narratives, and indecipherable jottings the artists who fascinate her featured prominently in their diverse creations. Her writing provides an illuminating guide to their mysteries and idiosyncrasies.

(The following excerpts from Peiry’s book have been translated from French into English by Edward M. Gómez. Copyright statements regarding the material published here appear below. The photographs that accompany this article show page spreads from Peiry’s book.)

by Lucienne Peiry

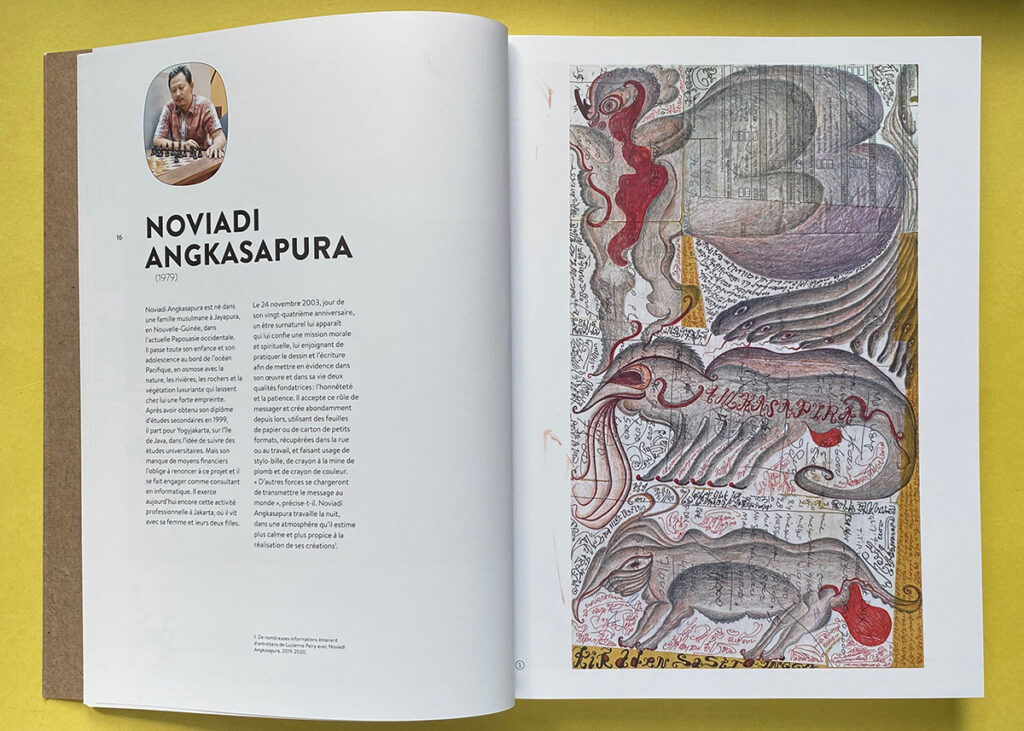

Noviadi Angkasapura (born 1979)

Noviadi Angkasapura was born into a Muslim family in Jayapura, on the island of New Guinea, [Indonesia,] in what is today the western part of the province of Papua. He spent all of his childhood and adolescence on the shores of the Pacific Ocean, absorbing, as though by osmosis, the nature, rivers, rocks, and luxuriant vegetation that would leave a strong imprint on him. After completing his secondary-school education in 1999, he departed for Yogyjakarta, on the island of Java, with the idea of pursuing his university studies. But his lack of financial means obliged him give up that project and instead he began working as an information-technology consultant. He still practices that profession today in Jakarta, where he lives with his wife and their two daughters,

On November 24, 2003, Angkasapura’s twenty-fourth birthday, a supernatural being appeared to him and assigned him a moral and spiritual mission — to practice drawing and writing with the goal of making evident in his work and in his life two fundamental qualities: honesty and patience. He accepted this role of messenger and, since then, he has created prolifically, using small sheets of paper or cardboard he finds in the streets or at work and also making use of ballpoint pens, regular graphite pencils, and colored pencils. […]

Rather than qualities that are discursive or rhetorical, the infinite combinations of lines, arabesques, and ornamentations [in Angkasapura’s compositions] deploy qualities that are visual and rhythmic.

The aesthetic of [his written] characters, executed with swiftness, resonate with the irreal and unsettling creatures — anthropomorphic or zoomorphic, scratchy, shaggy and long-haired — that appear, writhe, and sometimes contort themselves within spaces devoid of decoration or any backgrounds. Twisting and turning, the finely outlined inscriptions that surround or are attached to these figures, link themselves up in an interrupted flow, repeatedly breaking with the [overall] linearity. Angkasapura does not hesitate to change his medium in the course of creating. Often, he also alters the orientation of his iconographic motifs and of his graphic lines, delicately evading the notions of back and front. United from this point forward, word and image follow an expansive movement and proliferate until their saturate the [pictorial] space.

Arthur Bispo do Roasrio (1911-1989)

Descended from Black slaves, Arthur Bispo do Rosario was born in Japaratuba, in northeastern Brazil. No other official information regarding his birth and childhood has ever been gathered. It appears that, as a young boy, he was adopted by a cacao-growing family that lived near the border between the Brazilian states of Sergipe and Bahia, in which he would have learned to read and write. In 1925, when he was 14 years old, he practiced boxing; he served in the Brazilian navy for nine years but was discharged from the service for insubordination and a lack of discipline. From 1928 to 1936, the young Bispo do Rosario pursued a boxing career, then he went on to work at various jobs — hotel porter, electric-company employee, janitor, and domestic servant.

On December 22, 1938, at the age of 26, Bispo do Rosario experienced a psychotic break, during which Jesus Christ appeared to him, escorted by seven blue-haloed angels. A little bit later, he was overtaken by new visions, which revealed to him his healing mission — to recreate the universe so that he would be able to obtain redemption at the time of his own passing on into the hereafter. Diagnosed as paranoid-schizophrenic, in 1939, he was sent to a large psychiatric establishment in Colônia Juliano Moreira, a suburb of Rio de Janeiro, where he lived for 50 years until his death (except for brief stays outside the institution).

Bispo do Roasrio refused all medical treatments and therapies. Instead, he preferred to transform his cell, along with a dozen others, into art studios; he also set up a space for creating and storing his works within one entire pavilion. Following, as he said, the voice that guided him, often fasting, and abstaining from sex, there he created more than 800 works from which he did not want to separate himself, thereby affirming that, for him, they performed a life-giving function. He also declined all proposals to exhibit his creations. […]

Bispo do Rosario’s goal was to make an inventory of [all of] the objects of the urban, industrialized world so that he could present it to the Creator when he stood before him, following his death. In order to accomplish his earthly mission, he gathered, without moderation, all sorts of objects and materials that had been abandoned, used, or tossed into the trash; he accumulated them feverishly. […]

This gigantic inventory also includes a group of 14 large standards embroidered on their front and back sides; they were made with well-worn sheets from the asylum that are imbued with a sense of intimacy. In them, sometimes several sheets are sewn together to provide more body. These cloths are comparable to the giant pages of an illustrated encyclopedia and are meant to contain summaries of knowledge; on them are itemized, notably, the countries of the world with their respective flags; embassies; modes of transportation; and various sports. […]

[Describing another one of the artist’s textile works, Peiry oberves:]

Image, word, and ornamentation — all embroidered — all intertwine to confer on this transition garment that would open up to him the doors of the hereafter a metaphysical dimension.

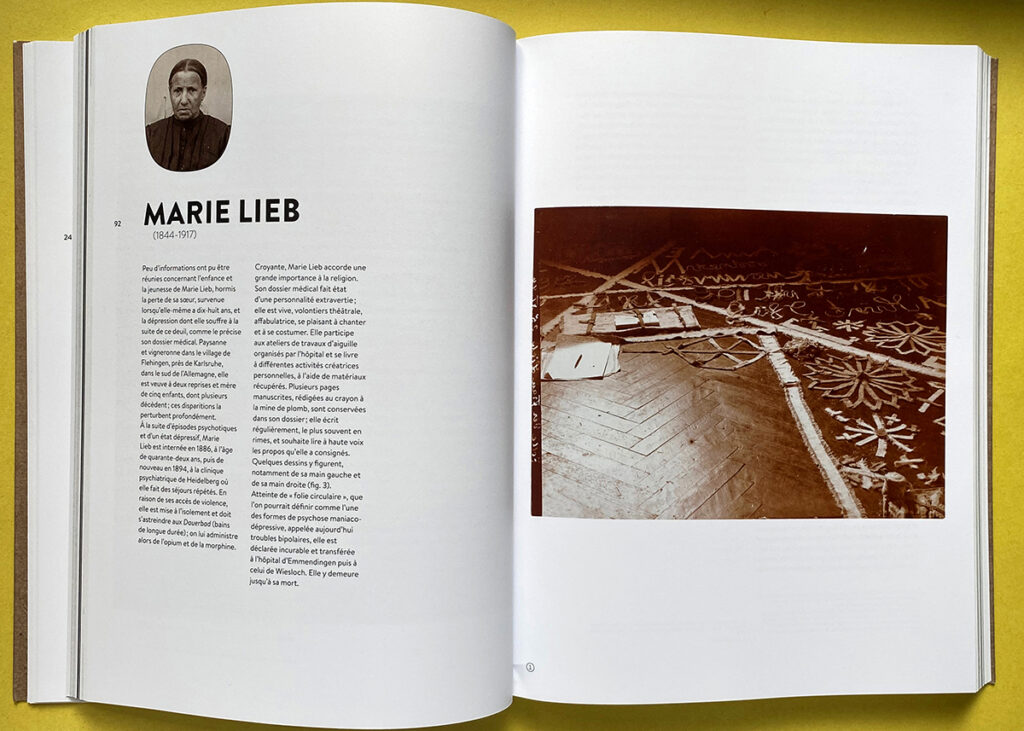

Marie Lieb (1844-1917)

Little information has surfaced concerning the childhood and youth of Marie Lieb, apart from the fact that she lost her sister, who died at the age of 18, and that Marie fell into depression following a period of mourning, as her medical file points out. A countrywoman and vineyard worker in the village of Flehingen, near Karlsruhe, in southern Germany, she was widowed twice and was the mother of five children, several of whom died. Their deaths profoundly disturbed her. Following a series of psychotic episodes and a period of depression, in 1866, at the age of 42, and again in 1894, Marie Lieb was interned at the psychiatric hospital in Heidelberg, where she would stay several times. Due to her violent outbreaks, she was isolated and sent to the Dauerbad (long-duration baths); she was given opium and morphine.

A devout believer, Marie Lieb assigned great importance to religion. Her medical records report that she had an extroverted personality; she was vivacious, willingly theatrical, and a compulsive liar, and she liked to sing and dress up. She took part in needlework workshops organized by the hospital and she engaged in various, personal creative activities using found materials. Several handwritten pages, marked up in regular graphite pencil, have been conserved in her medical file; she wrote regularly, most often in rhyme, and liked to read aloud in a loud voice the remarks she had recorded. Some drawings are to be found among those papers, notably of her left hand and her right hand. Affected by what was called “circular insanity,” which could be defined as a form of psychotic manic-depression, which today is called “bipolar disorder,” she was declared incurable and transferred to a hospital in Emmendingen and then to one in Wiesloch, where she remained until her death.

Today, Marie Lieb’s installations have disappeared. Apparently, their maker intended for them to be ephemeral and disassembled them several days after creating them, feverishly, in her cell or in the attic of the psychiatric hospital. This intervention — this playing with appearance and disappearance — reveals itself as surely having been stimulating, or even exciting, for her.

[As a participant in the needlework workshops,] Marie Lieb had access to textile materials, notably to bed sheets, from which she procured pieces, undoubtedly by pilfering them. First she would prepare the strips [of cloth] that she would tear and sometimes unravel, and then carefully roll up. Appropriating a space, she would transform a place of confinement, spreading out on the floor grand celestial landscapes, drawn and written out with her scraps of fabric in a gestural manner involving her entire body. According to the staff of the asylum, Marie Lieb would actively work on her compositions, then leave her installations intact for a few days. […] Mixing some inscriptions into her compositions, Marie Lieb brought together word and image; nevertheless, her writing remains indecipherable.

[Although only a very few photos of Lieb’s site-specific creations exist today, working from reproductions of such photographs, the Swiss contemporary artist Mali Genest, whose background is in art and in couture, recreated those works in 2017 on the occasion of the exhibition Inextricabilia, enchevêtrements magiques (Inextricabilia: Magical Entanglements), which Peiry curated for La Maison Rouge, in Paris. Genest kindly made photos of her reconstructions of Lieb’s works available to brutjournal for this article. Genest’s recreations of Lieb’s works will be on view in the Art Brut Writings: Wild Expression and Thought exhibition opening at Museum Tinguely in Basel, Switzerland, on October 20.]

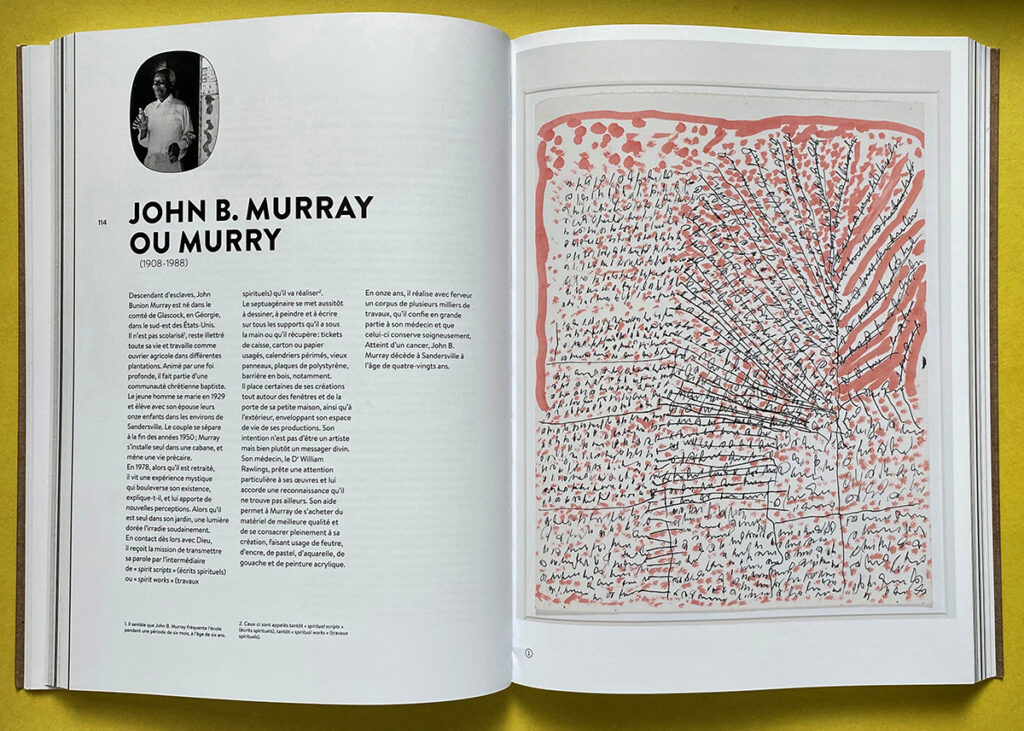

John B. Murray (or “Murry”) (1908-1988)

Descended from slaves, John Bunion Murray was born in Glascock County, Georgia, in the southeastern United States. He never went to school and remained illiterate all his life; he worked as a laborer on various plantations. Motivated by a deep sense of faith, he took part in a Baptist community. The young Murray was married in 1929 and, with his wife, brought up eleven children in the vicinity of Sandersville, Georgia. The couple separated toward the end of the 1950s; Murray moved into a cabin and went on to live a precarious life.

In 1978, now living in retirement, he had a mystical experience that, he said, shook up his existence and led to new perceptions. While he was in his garden, suddenly a golden light shone. From that point on, in contact with God, he was assigned a mission — to convey God’s word by means of “spirit scripts” or “spirit works,” which he went on to execute. The septuagenarian immediately started to draw, paint, and write on all sorts of support surfaces he had at hand or that he found and recovered, including, notably, cash-register receipts, used cardboard or paper, out-of-date calendars, old signboards, polystyrene planks, and wooden bars.

He placed some of his creations around the windows and the door of his little house, as well as on its exterior, enveloping his living space with his productions. He did not intend to be an artist but rather a divine messenger. His medical doctor, Dr. William Rawlings, paid special attention to Murray’s works and accorded him the kind of recognition he did not receive elsewhere. [Rawlings’] support allowed Murray to buy better-quality art materials and to dedicate himself completely to making art using felt-tip markers, ink, pastel, watercolor, gouache, and acrylic paint.

With fervor, over an eleven-year period, he produced a body of work comprising thousands of pieces, the bulk of which he entrusted to his doctor, who carefully conserved them. Suffering from cancer, John B. Murray died in Sandersville at the age of 88. […]

[Murray’s] “spirit scripts,” lacking any semantic content, are nevertheless conveyors of moral, life-saving messages he felt compelled to transmit. His body of work, which falls within the category of syncretic beliefs, is dominated by the sacred and by nurturing or harmful forces. His writing is marked by a religious and magical dimension of which the artist, like a shaman or a prophet, is the revealer of its secrets. In this way, it creates a link between the earth and the sky, between the here and now and the hereafter.

Present throughout a large portion of his artistic production, his inscriptions glide and weave their way all around and within anthropomorphic or totemic figures, made with hasty brushstrokes, which he often executed with two hands. Elsewhere, his scriptural characters form chains, one connecting to another in linear structures like the branches of a tree or in self-contained areas. […]

The loquaciousness of this illiterate African American constitutes a strong form of resistance, at once subtle and poetic, with regard to the dominant, word-centric society. In his artistic productions, Murray offers a renewed version of scripture linking his prolific body of work — and especially writing — to magic, the divine, and the invisible.

Giovanni Battista Podestà (1895-1976)

Giovanni Battista Podestà was born in Torre Pallavicina, a village in northern Italy. Following his father’s death, he left school at the age of ten and began working as a mason’s assistant to help provide for his family’s needs (he had 12 sisters). During his childhood and his adolescence, he lost six of his sisters, all of whom were stricken with tuberculosis. Called up by the Italian military in 1914 at the age of 20, Podestà headed to the front lines; he was wounded prior to becoming a prisoner of Austrian troops. His return home was difficult; he was affected by his war experience and he did not find work in rural Lombardy. The young man was forced to leave the countryside. First he worked as a policeman in the city of Laveno, on the shore of Lake Maggiore, then, in 1925, as an employee of a ceramics factory. He married that same year and became the father of two daughters. When World War II broke out in 1939, he was called up again, and he enlisted in Italy’s domestic service.

In Laveno, during his free time, Podesta executed his artworks in a studio he set up in the basement of the building in which he and his family lived. He also worked directly on the furniture and the interior walls of his small apartment. Once he retired, in 1956, he dedicated himself to his artistic creations. The rhythm of his existence was marked by his daily outings along the lake shore, where he used his own body as a mode of expression: his long hair fell down onto his shoulders, he wore a long beard, and he dressed up in costumes and sported accessories he had crafted himself as he paraded through the streets of the town proclaiming his moralizing pronouncements. The Swiss artist Marischa Burckhardt discovered his works and made them known to people around her, including, notably, her friend, [the artist] Jean Tinguely, who went on to collect them himself. Podestà died at home, as he had wished to do. […]

[Podestà] denounced a society in the grips of change, in which materialism imposed itself relentlessly, and he protested against the loss of moral, religious, and symbolic values. The totality of his artistic production is characterized by vivid color, shininess, and sparkle, and it overflows with pearls, sequins, pieces of broken mirrors, and metallic papers that he found, recovered and used to decorate his sculptures and high-relief works. Little banners, placed on all of his works, tend to have the same purpose — that of delivering a clear and immediate message coming from a will to educate and edify. […]

The solemn tone of his phrases corresponds with the declamatory pronouncements Podestà addressed to passersby. In writing as in speech, his words convey moral precepts that serve as an index of the great evils from which our societies suffer, including, notably, egotism, war, murder, theft, adultery, delinquency, and the cult of appearances. […] [In Podestà’s work,] ethics and aesthetics unite, thanks to writing, the figure, and painting.

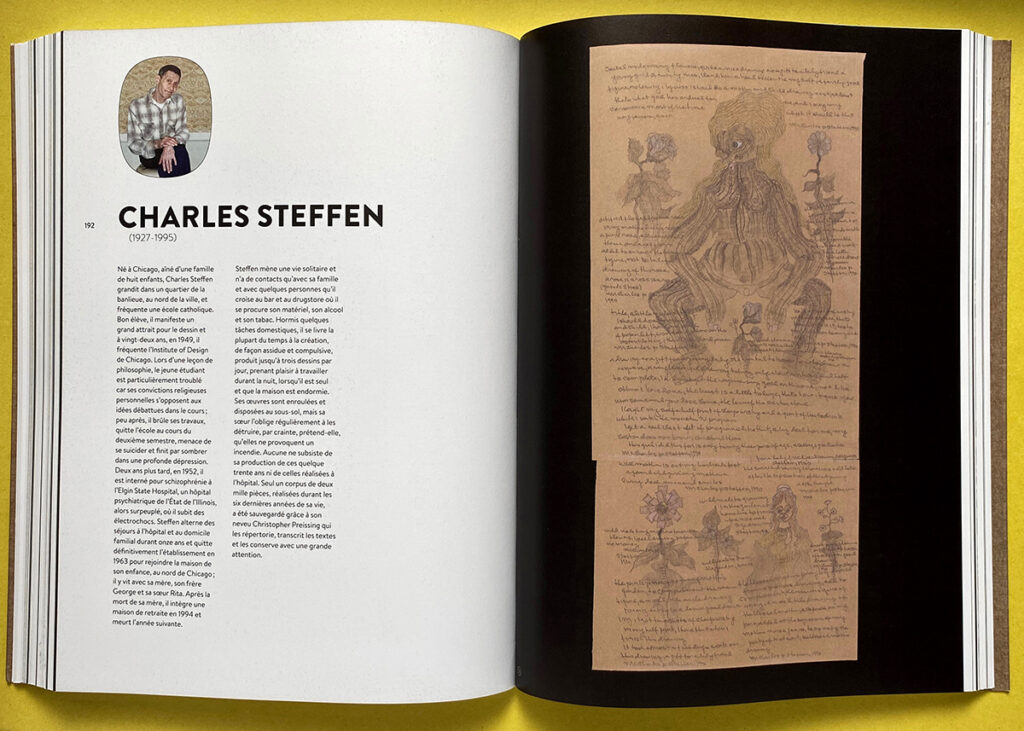

Charles Steffen (1927-1995)

Born in Chicago, the oldest child in a family with eight children, Charles Steffen grew up in a suburb to the north of the city and went to a Catholic school. He was a good student who displayed an attraction for drawing and, in 1949, at the age of 22, he attended the Chicago Institute of Design. During one philosophy class, the young student was particularly upset, because his personal religious convictions were opposed to the ideas that were being discussed. A short time later, he burned his works, left the school during his second semester, threatened to kill himself, and ultimately fell into deep depression.

Two years later, in 1952, he was sent for care for schizophrenia to Elgin State Hospital, an overcrowded psychiatric hospital in Illinois, where he underwent electroshock treatments. Over a period of eleven years, Steffen alternated stays at the hospital with stays at his family’s home and, in 1963, he left the psychiatric institution for good and returned to his childhood home, north of Chicago. There, he lived with his mother, his brother, George, and his sister, Rita. After his mother’s death, he moved into a retirement home, in 1994, and he died the following year.

Steffen lived a solitary life… […] Except for some domestic chores, he devoted most of his time to his artistic creations in an assiduous, compulsive manner, producing up to three works per day and taking pleasure in working through the night, when he was all alone, and the house was asleep. His works were rolled up and stored in the basement, but his sister obliged him to routinely destroy them out of fear that they might cause a fire.

[Peiry notes that most of Steffen’s works were destroyed, except for] a group of 2000 pieces, which were executed during the last six years of his life and were rescued, thanks to his nephew, Christopher Preissing, who catalogued them, transcribed their texts, and very carefully conserved them.

Female characters (his mother, the Virgin Mary, old classmates, or strippers), androgynous and hybrid creatures, self-portraits: Steffen’s figures take their places in a universe without any points of reference that is irreal and particularly enigmatic. He executed them on his dining room table, most often drawing on simple, large-size sheets of wrapping paper or on found and recovered paper bags that he sometimes patched together with Scotch tape. He used regular graphite pencils and colored pencils, materials that were simple and inexpensive. […]

Written right next to [images of] plants, flowers, and [various] characters, at first glance, [Steffen’s] texts resemble captions and give his compositions the allure of old, documentary, botanical or biological plates. Certain descriptive elements link up directly with their subjects, but the bulk of his remarks reveal an interior monologue. Brief phrases, with a jerky rhythm, link up with each other and seem to reflect the uninterrupted flow of his thinking, giving free rein to free-associating ideas, and to ruptures in and suspensions of thought.

Steffen’s daily life holds a central place in his work. Trivial details, recounted in a factual manner and in all their banality (his consumption of alcohol and tobacco, his meals, his brief encounters at a bar or at a drugstore, his small lottery wins) appear side by side with his personal thoughts and reflections. […] As though taking part in a lucid conversation with himself, he opened himself up equally to commenting about and the appreciation of his own creations, confiding his pleasure in depicting nudes, night after night, avoiding the feeling of guilt that he should have had in doing so. […] Word and image, united in a distinctive partnership, offer us the troubling impression of listening in on Steffen’s internal voices.

* * * *

The original, French-language texts by Lucienne Peiry, published in Écrits d’Art Brut: Graphomanes Extravagants: © 2020 Éditions du Seuil, Paris.

The English-language translation of excerpts from the above-cited book that are published here: ©2021 Edward M. Gómez

The content of this magazine article may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, by any means, without the permission of the designated copyright holders.

Below: Poster for the exhibition, curated by Lucienne Peiry, which will open at Museum Tinguely, in Basel, Switzerland, on October 20, 2021, and run through January 23, 2022.