THE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART TOKYO RE-EXAMINES IMPORTANT WORKS IN ITS COLLECTION, REVEALING SOME CONCEPTUAL-ART GEMS

by Edward M. Gómez

TOKYO — When I first spent an extended period of time in Japan in the late 1980s, as a Fulbright Fellow doing original research about the activities and accomplishments of some of the country’s most notable modern artists and art movements of the post-World War II era, back in Europe and the United States, little was known about this slice of modernism’s broader history. At that time, most overseas curators, galleries, media outlets, and book publishers were quick to dismiss works of Japanese modern art, about which they knew nothing, as little more than imitations of Western modernist styles.

Although no one knew it at the time, that moment would turn out to be the tail end of a decades-long period of rebuilding, the final chapter in the story of postwar Japan’s remarkable, so-called economic miracle, which came to a screeching halt at the beginning of the 1990s as the result of the collapse of a “bubble economy” fueled by greatly inflated real-estate and stock prices. During the boom-boom years of the 1980s, some American and European economists, as well as political and corporate leaders, worried about “Japan as number one” — about its potential, that is, to become the world’s most powerful economy.

Meanwhile, the foreign media could not get enough of Japanese postmodernist architecture, industrial design (led by just about every innovative new gadget Sony introduced), fashion, food, movies, and other cultural productions. In cities all across Japan, new museums, many of whose designs showcased the talents and embodied the aesthetic visions of the country’s most inventive architects, seemed to pop up every month. I still vividly remember the opening of the Yokohama Museum of Art in late 1989, a behemoth of a building designed by the modern architect Kenzo Tange, and the eagerness with which many museums in Japan sought to acquire exemplary works of foreign modern art for their collections.

At that time, art students in Japan were hard pressed to find in-depth, extensive courses in their universities and art academies focusing on the history and development of Japanese modern art. Instead, they sought information in magazines and exhibition catalogs. The Internet had not yet appeared. Occasionally, in books like the art historian and curator Shigeo Chiba’s Gendai bijutsu itsudatsushi (Contemporary Art’s Missing History; Tokyo: Shōbunsha, 1986), Japanese modern-art history received overdue serious, critical attention in an international context.

In recent decades, both in Japan and overseas, especially on the part of certain museums in Europe and the U.S., much more attention has been paid to Japanese modern art through research and exhibitions, and the story of its evolution and of Japanese modern artists’ accomplishments has been folded into the broader narrative of modernism’s evolution.

In New York, the Guggenheim Museum and the Museum of Modern Art have mounted some noteworthy exhibitions in this field; elsewhere in the U.S., such museums as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, have also presented significant exhibitions of modern art from Japan or now include works in this category in their permanent collections.

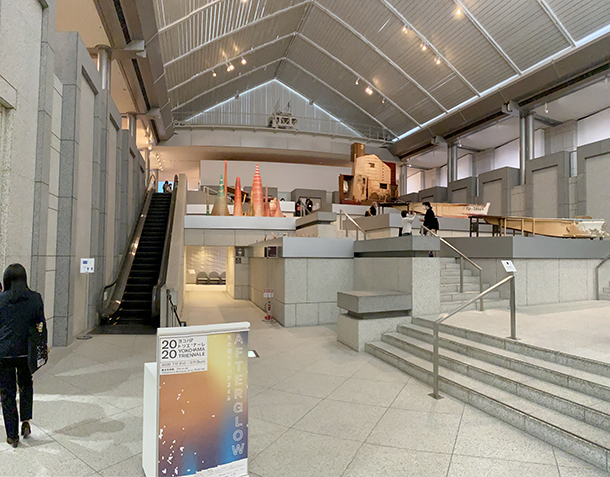

For a long time in Japan, no one museum served as a kind of anchor institution housing a more or less encyclopedic survey collection of Japanese modern art, but this situation changed in 1995, when the new Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (known as “MOT”) opened, absorbing the considerable holdings of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum. Today, MOT counts some 5500 works from Japan and other countries in its modern- and contemporary-art collection. Right now, through October 16, the museum is presenting MOT Collection: Rewinding the Collection 2nd, an informative and revealing exhibition showcasing some of its Japanese modern-art treasures.

This exhibition is a sequel to MOT Collection: Rewinding the Collection, which opened in 2020 just as the worldwide coronavirus pandemic was erupting. That show ran through June 2021. Curatorially, both of these exhibitions have re-examined certain works among the museum’s Japanese modern-art holdings, both with regard to their presence within an expanded, specialized collection and also within the context of the above-mentioned more inclusive, more complete telling of modern art’s international development that is now being elaborated by a new generation of art historians and curators in Japan and overseas.

To see the many iconic works of Japanese modern art, along with other, less well-known paintings, drawings, mixed-media objects, and other creations that MOT has tucked away in its vaults now displayed in a judiciously chosen exhibition like MOT Collection: Rewinding the Collection 2nd is to appreciate the various currents of technical experimentation and critical thinking — aesthetic, political, social, cultural — that informed and shaped the productions of some of Japan’s most original artists.

With this month’s conceptual-art theme in mind, here are a few highlights from MOT’s current exhibition that relate to it in various ways.

Natsuyuki Nakanishi (1935-2016), “Clothespins Assert Churning Action,” 1963/1981:

In 1958, Nakanishi earned a bachelor’s degree from the prestigious Tokyo University of the Arts, where he had studied oil painting. Along with fellow artists Jirō Takamatsu and Genpei Akasegawa, Nakanishi was a co-founder, in 1963, of Hi-Red Center, an artists’ collective whose provocative performance-art events, which its members carried out in public spaces, expressed the experimental, transgressive spirit of Japan’s avant-garde in the 1960s. Earlier, he had been a member of the Neo-Dada Organizers, an “anti-art” artists’ group.

“Clothespins Assert Churning Action” is one of Nakanishi’s most iconic works, which examines and questions the nature of painting itself. The artist was especially interested in the material character of paintings and in the physical space in which they existed and were perceived. In this large, multi-panel work, he clipped hundreds of metal clothespins to the surfaces of stretched canvases, in effect “painting” with them to create a three-dimensional object that defies expectations of how, typically, a painting should appear and of the form it should take.

In a related performance-art piece, Nakanishi walked around Shinbashi Station in Tokyo, covering his body with clipped-on metal clothespins and carrying balloons.

Hi-Red Center (founded in 1963), “Campaign to Promote Cleanliness and Order in the Metropolitan Area,” 1964:

For Hi-Red Center, the city itself was a canvas, stage, and laboratory for its subversive happenings — art-action events that called attention to and challenged commonly held notions about authority, social behavior, and the role of the individual in society. The group carried out its “Campaign to Promote Cleanliness and Order in the Metropolitan Area” in Tokyo’s posh Ginza shopping district during the run of the 1964 Summer Olympics, which took place in the Japanese capital and was widely viewed as a symbol of a modern, rebuilt, democratic Japan’s return to the world stage in the post-World War II era.

Hi-Red Center’s art happening, in which the group’s members, wearing face masks and lab coats, and employing brooms and cleaning cloths to meticulously tidy up stretches of sidewalk, alluded to the clean-up efforts Japanese and Tokyo government officials had made — including removing homeless people — to clean up the city in preparation for the Olympics.

Mitsuko Tabe (born 1933), “Placard,” 1961:

Tabe, who is based in Fukuoka, on Kyūshū, the southernmost of Japan’s four main islands, was a member of Kyūshū-ha, a group of avant-garde artists that was active from 1957 through 1968. As a thinker and artist, Tabe has used her art to reflect and express, sometimes quite allusively, her interests in the natural environment and various issues related to the status of women in society and female identity.

In 1961, she made five mixed-media works in her “Placards” series, three of which are now on view in MOT’s exhibition. In them, she used photo imagery clipped from magazines that referred to American popular culture and also to war. Some of the works in the series allude to African-American jazz music or to Africa, a continent on which former European colonies were still emerging as independent nations in the early 1960s.

The piece from the “Placards” series that appears here, above, includes an adulterated American flag. Could it refer, disapprovingly, to the strong influence of the U.S. on postwar Japan or to Uncle Sam’s early involvement, prior to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s sending of American combat troops to Vietnam in 1965, in the war that already had been unfolding in that country since the late 1950s? Graphically, Tabe’s “Placards” are arresting works of art.

Mieko (Chieko) Shiomi, “Endless Box,” 1963/1990:

As a visual artist, performer, and composer of music, Shiomi was one of the principal participants in Fluxus, the international community of avant-garde artists who were most active in Japan, the U.S., and parts of Europe in the 1960s and the 1970s. In Japan, she was a co-founder of Group Ongaku, a postwar collective of avant-garde music-makers.

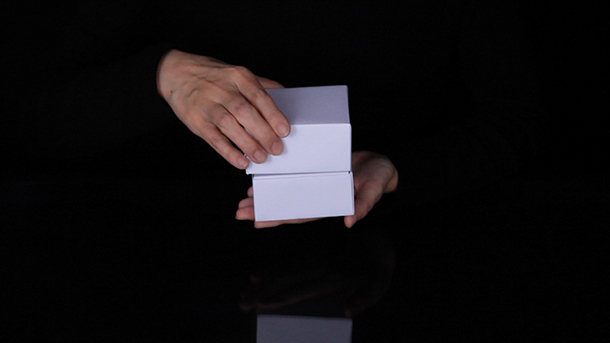

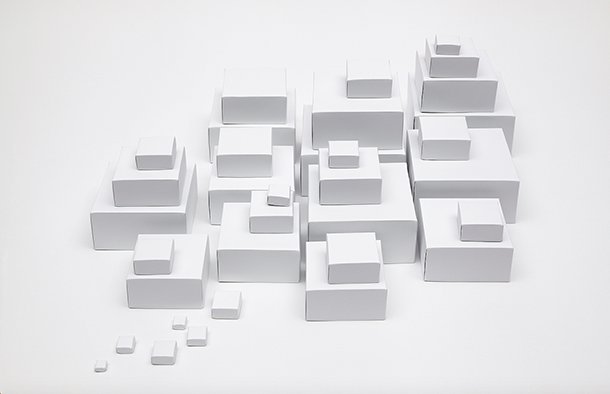

Both the idea on which it is based and to which it gives tangible form and the execution of Shiomi’s ingenious “Endless Box” are quintessential examples of the cleverness at its best that characterizes the most imaginative conceptual art. Her multi-part box consists of a large quantity of lightweight-cardboard, rectangular-shaped boxes that fit into each other like stacking dolls.

In the MOT exhibition, the actual boxes that are the component parts of Shiomi’s artwork are displayed in a clear-acrylic vitrine. A simply shot, accompanying video shows a pair of hands carefully and methodically opening the artist’s box and then endlessly removing one box after another from the tightly stacked units that make up the complete “Endless Box” until only a teeny-tiny box remains.

Tatsuo Miyajima, (born 1957), “Keep Changing, Connect with Everything, Continue Forever”:

Miyajma studied oil painting at the Tokyo University of the Arts, from which he earned an undergraduate degree and a master’s degree. Earlier in his career, he was interested in performance art but after becoming involved with LED lights and digital technology, in effect, he created works of art that were able to perform on their own without his personal intervention or appearance.

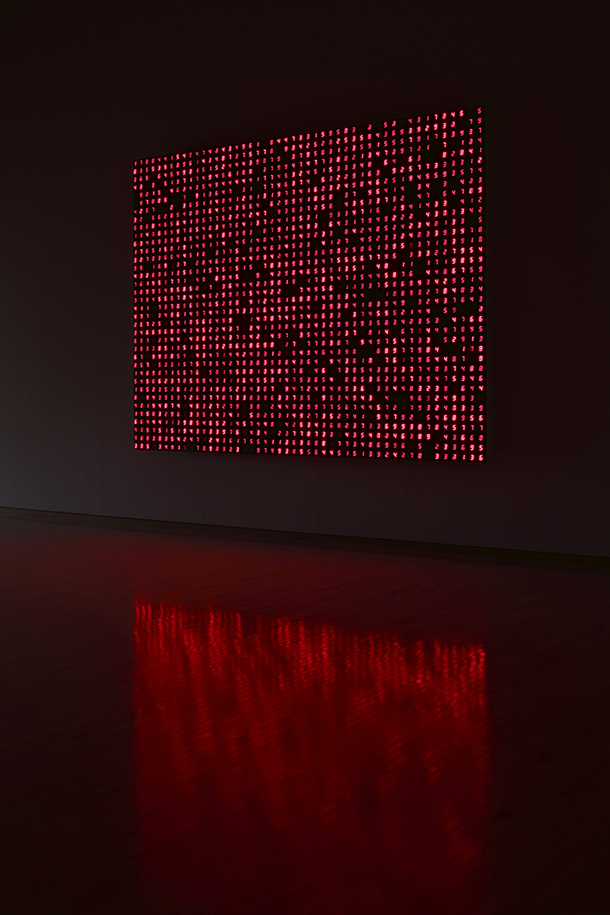

Miyajima is best known for his works employing LEDs whose endlessly flickering numbers, from 1 through 9, call attention to the passage of time without necessarily measuring it, and give visible form to the artist’s interests in the phenomena of time and space, often in relation to aspects of Buddhist thought. For Miyajima, the phrase “Keep changing, connect with everything, continue forever” has long served as a motto of his entire body of work and as a personal, artistic-philosophical credo.

In this emblematic Miyajima work, consisting of 1728 constantly flickering LEDs, each one flashing the numbers 1 through 9 at its own programmed speed, a monumental wall of dynamic light seems to exude a life force along with the luminous glow that radiates from its surface. At MOT, it has been installed inside a high-ceilinged, dark room with a single bench placed a good distance from the glowing panel, like a pew in a church facing an altar.

Indeed, this signature work of Miyajima’s is nothing if not majestic and spirit-lifting in its visual impact. With it, he has created the equivalent of the stained-glass windows of Chartres Cathedral for our digital, plugged-in, high-tech era. Infusing cool technology with a shot of warmhearted soul, he has produced a masterpiece of conceptual art that gives captivating form to the most ephemeral of ideas.