FROM ANY VANTAGE POINT TODAY, DOESN’T IT SEEM AS THOUGH THE WORLD HAS GONE MAD? NOW, A PORTFOLIO OF ARTISTS’ RESPONSES TO THE PROPOSAL “MAKE ART, NOT WAR”

by Edward M. Gómez

That dauntingly loud sound you now hear rolling out across continents and across the seas with the fury of a tsunami’s roar is that of the human family’s collective sense of angry exhaustion, an utterance at once urgent and unstoppable that has arisen from the most profound depths of anguish and despair.

It’s the sound of exasperation mixed with rage. Of impatience wrapped in fear. It’s the sound of societies, communities, families, and individuals everywhere that have been worn down by the destructive effects of global warming, political instability, economic uncertainty, out-of-control technology, and unsettling, rapid — or sometimes not swift enough — social change.

It’s the sound of decent, honest, hard-working people around the world who have suffered all they can under the rule or influence of corrupt, dishonest politicians and greedy, destructive corporate powers, and who have given up on the social and political institutions — courts, congresses, international justice and defense organizations — that should be protecting them and doing so with courage and resolve but which instead only demonstrate time and time again their allegiance to the status quo and their members’ skill at kicking rusty cans down the road.

That big sigh is the sound of the world’s peoples recognizing that they have had enough of all the lying and double-talk that flow from the mouths of political leaders and the platforms of mainstream “news” media that together lack the courage to speak truth to power. (In the United States today, this includes any and all politicians who and media outlets that still hesitate or refuse to acknowledge that the single greatest threat to the country’s existence is that of the Trump fascists; at this point, they still refuse to admit that American fascism, which has been nurtured over many decades by the racism-fueled Republican Party, is now a frightening, trigger-happy reality.)

Above all, that big sigh is the sound of all sensitive, compassionate, intelligent people around the world who believe that the time has come to stop making war.

With such pronouncements as “Wars are not paid for in wartime; the bill comes later,” Benjamin Franklin, the 18th-century polymath who helped write the United States’ Declaration of Independence, proved to be one of the most anti-establishment-sounding members of the elite American establishment he played such a big role in, uh, establishing.

With a nod to Franklin’s wisdom and against the backdrop of the human family’s current, soul-deep malaise, which has been exacerbated by the ravages of a global pandemic and new or ongoing wars in Ukraine, Yemen, Syria, Tigray, and other parts of the world, we asked artists to share their thoughts and creations in response to the theme “Make art, not war.” Good artists are good thinkers and, implicitly, given the nature of their work, communicators and educators, too. Some of the images, performances, objects, and other creations a group of artists shared with us directly addressed our theme; others touched upon it more subtly or gently.

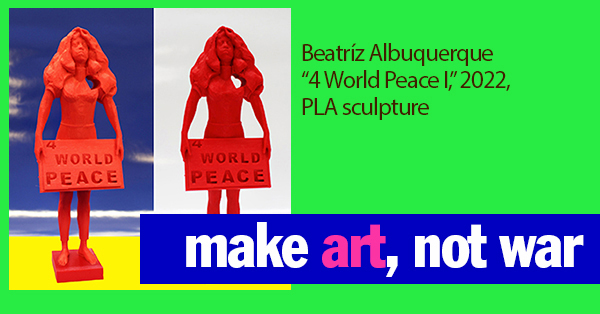

Portuguese-born Beatriz Albuquerque (Instagram: @beatrizalbuquerqueweb), who divides her time between Porto and New York, has been using 3D printing to make sculptural works. About her “For World Peace” series, she noted, “This is an on-going project that started in New York and is comprised of performances and 3D-printed figures showing myself holding a signboard; [it’s about] bringing awareness in the streets, through activism, to ending war and violence. I believe that art is political, and that we can communicate through the arts to bring changes in perspective and shifts in thinking.”

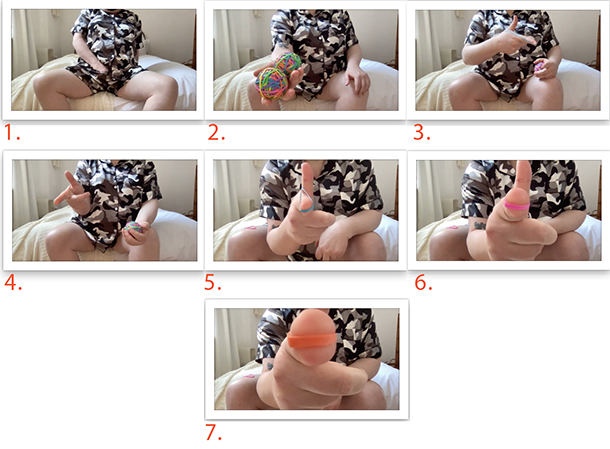

Laurel Jay Carpenter is an American performance artist (Instagram: @laureljayjay) living in the United Kingdom whose work, she says, has often “resided on the margins” and offered critiques of “capitalist forces within the art market.” Her clever piece “Take It Away” (above), which she performed via live stream for Norway’s PAB Open Festival earlier this year, uses simple gestures and few props — just two balls of rubber bands, from which the artist mischievously releases just a few — to allude to a handgun and evoke a sense of aggression and menace.

Commenting more generally on how artists might respond to war and violence, just as they might react to many other subjects or events, Carpenter told us, “What art and artists are so good at is pointing toward the complexities or the gray areas and being present in the discomfort of [what is] unknown, shifting, and ambiguous. [Artists are good at] listening, noticing, questioning. I think anyone who works consistently in this way could not not be affected by the circumstances of our world [today]. We feel it. And what we notice, question, and feel becomes part of [our] work.”

Artists, Carpenter added, may share the same skills and concerns that can be found among people in many other walks of life, but artists often have an ability to “crack open” an approach to thinking about or reacting to “a conversation, a thought, a feeling, or a connection,” because, she noted, that is their role — “to make these matters matter.”

Valery Oisteanu (Instagram: @zendadanyc) is an avant-garde artist and poet who was born in the former Soviet Union in 1943 and was later educated in Romania. His personal website notes that, “[a]t the age of 20, he adopted Dada and Surrealism as a philosophy of art and life, and a few years later English as his primary language.” A maker of collage and assemblage works, in 1972, Oisteanu immigrated to the United States.

In response to our “Make art, not war” theme, he sent us a photo of one of his latest creations, a simple but symbolically rich pair of glass jars filled with bright-red, plastic bottle caps and jar lids. These companion pieces refer, of course, as the artist noted, “to the blood of Ukrainian and Russian soldiers” who have died in the conflagration Russia’s leader, Vladimir Putin, ignited when he ordered his army to attack Ukraine earlier this year.

Regular brutjournal contributor Steven Hirsch (Instagram: @stevenhirsch), a veteran newspaper photographer and a multi-genre visual artist, whose strange, buoyant beach scenes, shot through a telescope, are featured elsewhere in this month’s issue, was uncharacteristically terse and sounded unusually glum when he responded to our inquiry about art and war. In March of this year, shortly after the start of the war in Ukraine, Hirsch instinctively began making paintings in response to the inundation of news about and horrific images of war victims’ suffering. “I’m sorry that I cannot write about these paintings,” he told us, adding, “They are very hard for me to look at or discuss, even today, several months since the start of the war. The pain and suffering of the war’s victims, and the brutality and horror of it all — it’s overwhelming. I have few words and I hope the paintings express my feelings.”

The Los Angeles-based collage artist Lou Beach (Instagram: @420characters), whose work we introduced in brutjournal’s June issue, has made numerous pieces alluding directly, and often with humor, to political themes. Thinking about art and war, Beach observed, “Of course, the job of the artist is to respond to war, violence, et al, but not any more than it is to respond to peace and harmony and angels and sex. Should an artist respond? I do not like shoulds.” Having said that, Beach added, “One of my collage heroes has always been [the German artist] John Heartfield [1891-1968], whose work was almost exclusively political and [created] in response to the rise of Nazism and the horrors of war. Heartfield was a master artist as well as a master propagandist.”

By contrast, the conceptual, digitally produced images of the Brooklyn-based artist Susan Silas (Instagram: @susansilas) in her ongoing “Phantom Limb” series are more subtle and nuanced, and perhaps purposefully obtuse, the better to seize viewers’ attention and prompt them to look deeply at and contemplate these rectangles of color accompanied by narrative captions.

Above, for example, Silas’s own caption for “The Last Jew in Vinnitsab” says, in part: “They are standing in a small clearing. The young soldier on the left gazes off into space. There are three soldiers in uniform altogether. There are four other men. They are dressed in civilian clothing. […] In front of them stand two naked men. […] The two naked men stand at the edge of a pit. It is not possible to see how deep it is.”

Silas explained, “‘Phantom limb’ is a term used to describe the experience of amputees who can still feel a limb that is missing. It may ache or itch, but it isn’t there. There are images that one sees that stay in the mind and that was the association that prompted my series’ title.”

In Silas’s “Phantom Limb” images of obscured images, the artist uses software to obliterate photos of dead migrants or violent war scenes by covering them with solid blocks of color. Silas noted, “Literally, an image lies beneath [each block of color], and each color is picked from one pixel in the [underlying] image.”

From his native New Zealand, the artist Stuart Shepherd responded to the art and war theme by relating it to more everyday human interactions away from the battlefields of the deadliest wars and thinking about it more in terms of more ordinary, daily interactions, which, as an image-maker, he likes to capture in paintings on paper.

In “The Reluctant Baptism” (above), Shepherd found himself thinking about “a baptism, with a preacher and a reluctant disciple”; he was recalling an incident he had witnessed in the harbor area of his seaside town, in which a young man bit a minister’s hand while a baptism was taking place, and the artist was fascinated by this odd, most unexpected kind of physical attack. In the very broadest terms, he mused, the seeds of war may be planted in violent, aggressive behavior, no matter how small-scale it might appear to be.

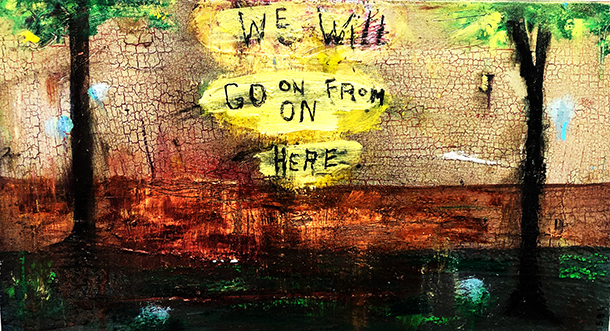

The New York-based artist Stephanie Brody-Lederman (Instagram: @stephbrodylederman) is something of a doyenne among painters who have long mixed textual elements and images in their work; Brody-Lederman’s art is atmospheric and filled with free-floating emotional-psychic energy. Sparse brushstrokes and a vocabulary of recurring motifs — trees, lanterns, tables, rowboats — along with snippets of overheard conversation or buzz phrases from news reports come together in the artist’s compositions to create portraits of fleeting moments in time.

As a wife, mother, and grandmother, and as a member of various close-knit communities, Brody-Lederman is someone who has always tried to look at a glass half full and who has been known to say, to herself as much to any friend or acquaintance to whom she might want to offer encouragement, “Just put one foot in front of the other — and then do it again and again.”

Thus, as bad as the situation in the world is today — even as I was compiling this report, two friends dispatched e-mail messages expressing their sense of despair at the news of the U.S. Supreme Court’s most recent, destructive rulings — Brody-Lederman sent us a photo of one of her optimistic-feeling paintings from two years ago, when the pandemic was breaking out, and the prospect of all-out war in Ukraine was not on many radar screens. Her painting’s title: “We Will Go on From Here.”

The artist said, “In order to exist in these horrible times, I find that I must force myself to see the beauty in our everyday lives. Otherwise, I would not be able to survive. Memories of someone singing, or of a beautiful day in May — that is what sustains me.”

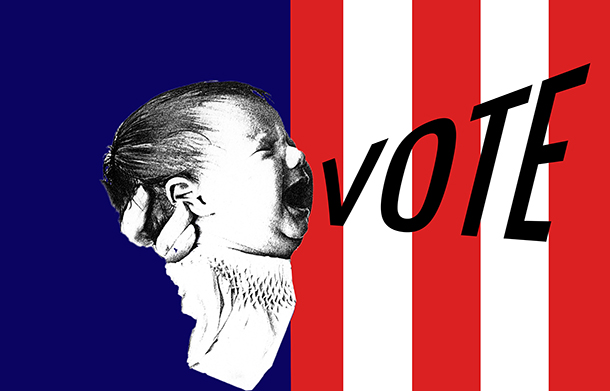

The artist Debra Pearlman (Instagram: @debra.pearlman), who is also based in Brooklyn, created “Babies Can’t Vote” in 2018; it was shown in the inaugural exhibition of the short-lived Center for Contemporary Political Art in Washington, D.C. Both the exhibition and the art center emerged in response to the Donald Trump’s “winning,” with Russia’s help, of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Pearlman told us that she often has made art “in response to the life-and-death necessity of voting,” and noted, “My images are often of children, the ultimate victims” — of whatever happens politically or of whatever laws might be passed, that is.

As far as our “Make art, not war” theme is concerned, “Babies Can’t Vote” may seem a bit remote, but broadly speaking, we grasp the point this powerful image and its creator are making, namely, that in what’s left of the United States ailing’ democratic system, one of the main ways of effecting change is by voting out ineffective, unreliable, or corrupt politicians and voting in more capable representatives of the people, including and especially those who pledge to work on eliminating violence in society and who will favor diplomacy over making war — and, of course, the needs of children, from among whom will emerge society’s future leaders.

One of the most heartfelt responses to our call for artists’ thoughts about or works related to the “Make art, not war” theme came from Marianne Loner, the mother of Fleming Loner Lentakis, a New York-born iconoclast who wrote short stories, played the guitar and the saxophone, ran a recording studio for several years, traveled extensively — and with gusto — and produced collage and photographic works. Lentakis died of heart and lung failure at his home in Miami in 2020, just a few days after his 44th birthday.

About her son, his outlook on the world, and the satisfaction he derived from his art-making and creative pursuits, Marianne Loner said, “In the face of decades of war all over the world, Fleming became convinced that all people, and especially artists, must not only bear witness and resist violence but also remember that the world is multifaceted and abundant — and they must show [that understanding]. His stories pay attention to little details, making connections between them as well as treating humble people and outsiders with dignity and [acknowledging their] right to simply be.”

In Marianne’s fond evocation of her late son’s sensibility, especially in the last part of her remarks, lies, in effect, a vivid description of a current of compassion and spirit of community that, together, engender a force that is the very antithesis of violence and war.

Powerful but elusive, it is one that shapes the ideal conditions for nurturing the human spirit and offers a timeless tonic for anguish and despair.

It has a name.

We call it “peace.”