by Edward M. Gómez

“Gimme some truth,” John Lennon sang in a song of the same name on Imagine, his second solo album, which was released in 1971, following the break-up of the Beatles. Like the whole of his first solo album, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, which had come out in late 1970 and was marked by its spare production and the forthrightness of its introspective messages, the song “Gimme Some Truth” states its demand with unfettered clarity. As he stepped away from the world’s most famous rock band but still lived in fame’s glaring limelight, Lennon strove in his solo work to communicate straightforwardly and honestly, replacing rock-star spectacle with expressions of his search for personal authenticity.

Lately, we’ve been thinking about what it means for something or someone to be authentic, which often echoes what it means, literally or figuratively, to be clean, honest, unfiltered, or pure. Maybe it’s the feeling of yuckiness all over — of unstoppable contamination caused by the coronavirus in all its pernicious, varied strains, and of destructive human-caused pollution, that has led to global warming and worldwide climate change — that has prompted a yearning for something — anything — that is clean, unadulterated, pure.

Moreover, in a world of image-and-information overload, with non-stop inundations of lies pouring from the mouths of politicians and corporate spokespeople, fake news, and hype just about everywhere one turns, does “purity” mean anything anymore? Not in a moralistic sense, although that which is pure often has been associated with that which is honest, direct, and unfiltered, but rather in an aesthetic sense? In many fields of art — geometric abstraction, for instance, or countless examples of classic modern architecture — the expressive power of pure form alone has been celebrated even as it has been employed to convey all sorts of spiritual, philosophical, or idealistic values and meanings.

Musing about purity, we washed our hands, brushed our teeth, and spoke with a few artists and image-makers about purity. Then we went out and did the laundry — using a clean, eco-friendly detergent, of course. The label on its bottle proclaimed that it was “pure.”

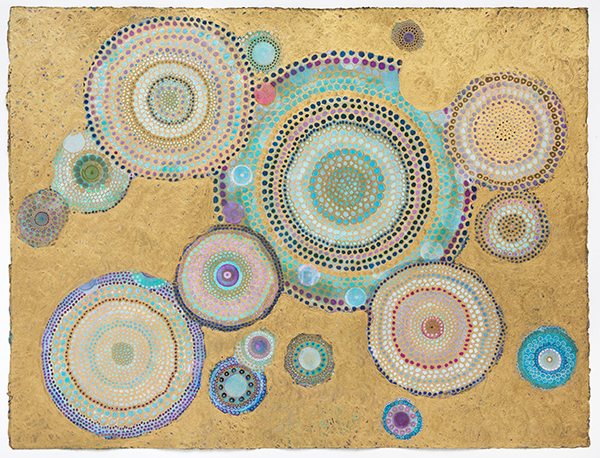

We got in touch with the artist Olivia Munroe, who, after living and working for many years in Connecticut, recently downsized and moved to New Mexico. In her art, which has been influenced by ancient mandala imagery, her study of Buddhism, and her interest in color and geometry, she conjures up compositions that pulse with a slow, quiet, soothing energy.

Munroe said that, for her, when it comes to art, purity has to do with “beauty, symbolism, and form” and with channeling “the timeless essence of line, circle, and square, which all humanity has known, to respond to the universal language of geometry and communicate on a level playing field to make art that almost any being can relate to in some way.” Recognizing a thematic link between that which is pure and that which is authentic, Munroe added, “Purity relates to the essence [of something]. Purity is transcendent — it expands beyond the thing itself.”

advertisement

Such heady thoughts offer echoes of the very earliest thinking about what came to be known as aesthetics, the branch of philosophy that examines the nature of beauty, art, and taste. For some ancient Greek philosophers, the good, the true, and the beautiful shared essential characteristics. What would Apollo and the Muses have made of an afternoon spent away from the music room and their gentle strumming of the lyre, only to be replaced with a few hours scrolling through TikTok?

40×40 inches (101.6 x 101.6 centimeters). Photo courtesy of the artist

We reached out to the New York-based painter Stephanie Brody-Lederman, who over the years has developed and refined a simple-looking but symbolically resonant vocabulary of frequently used images, which she combines with snippets of text — words and phrases that pop up in conversation, or that she overhears, or that she picks up from newspapers or media broadcasts. Together, the elements of Brody-Lederman’s paintings come together in compositions that capture the spirit of free-flowing, hard-to-label emotional or psychological currents.

Brody-Lederman weighed in and observed, “I find purity to be a conceptual term, and my concept [of ‘purity’] is ‘to thine own self be true.’ In order to make art that evinces purity, I find that I must be completely myself. I must be true to my insights, experiences and philosophical leanings. When my work is successful, it becomes a genuine aspect of who I am at the time I am making it. That is purity in art to me.”

Climbing down from the Olympian heights of such ruminations, our gossamer togas billowing in a late-autumn breeze (we had washed them earlier in that eco-sensitive soap), we grabbed our lyres and caught up with the artist Daisy Craddock, who keeps a studio in a small town in the mid-Hudson Valley, north of Manhattan.

For many years, Craddock, a skilled painter of trees whose pastel drawings of trees and landscapes are lush and full of visual textures, has been making a series of diptychs in pastel on paper. Each set of images depicts the outer skin and inner flesh of a particular kind of fruit or vegetable. Even more than pure form, pure color and a play of light on her paper’s surface are the raw materials of these remarkably accurate — and somewhat enigmatic — not-quite-abstract abstractions.

Craddock told us that, in these works, in effect, she purposefully toys with the notion of pure color when it comes to the impact she intends for them to have on viewers, even as she remains faithful to — or “pure” with regard to — her subject matter.

She explained, “Although, in these diptychs, I use the same oil pastel and Arches paper as I do in my landscape studies, these works appear to be abstract blocks of color. Drawn from life, they depend on an ‘Aha!’ moment, when a viewer realizes these are up-close depictions of the skin of a fruit or vegetable on the left and its flesh on the right — or maybe not. Devoid of what I call ‘the space between,’ these diptychs are built up of many layers; they’re scumbled, scraped and burnished by hand until they’re also about surface sheen, or incidents such as fingermarks and wipes, and of course color, always about color.”

We also checked in with Margret Avery, a longtime hair and makeup artist who is also a singer and performer; we were interested in what someone whose creative, professional activity involves the shaping of her own and other people’s visible images might have to say with regard to purity insofar as, aesthetically speaking, this notion might inform or influence her work. Avery, who has prepared fashion models, corporate executives, and Broadway stars to face the cameras — and, first of all, to bravely face their own mirrors — said, “I believe that ‘pure’ does mean ‘authentic,’ because, when it comes to shaping one’s image, the choices a person makes tend to come from a deep desire to be a collaborator with his or her own dreams.”

Avery mentioned that some of her clients favor “a full-on painted face, with lashes, liner, and hairpieces,” while others “don’t like much makeup at all.” Either way, she suggested, she recognizes a certain kind of purity of purpose or intention in the many diverse ways in which people choose to create a personal style and look, and present themselves to the world.

Morgen Schick, a former fashion model and the creator of an eponymous line of cosmetics that was sold for many years during the early 2000s, now promotes the Active Argan range of skin-care products, whose key ingredient is oil from a tree nut grown in Morocco. Since we’re nuts for candid, no-nonsense information about taking care of the body and about aging both healthily and gracefully, we asked Schick to share her thoughts on what purity means to her as a specialist in what’s known as the beauty industry.

The New York-based entrepreneur said, “For me, purity equals authenticity, and authenticity equals purity. It’s pretty simple. When I think of purity, I want it in every aspect of my life — I want my food to be pure, I want my skin care to be pure, I want my image to be pure. On a daily basis, I have to remind myself that it is more important for me to be my purest, most authentic self at 57 years old than to succumb to the pressures of the media, of social media, of all of these other platforms that keep telling me that 57, in your purest form, is not good enough.”

Schick added, “As an image creator, someone who styles and does makeup and teaches women that they are enough, I’m telling them: ‘Don’t listen to the noise! Stay pure. Let’s work within the millimeters [as opposed to undergoing radical plastic surgery, for example], so you still look in the mirror seeing your authentic self, but we’re [just] optimizing with makeup, hair, and skin care.’ Purity is authenticity. Authenticity is purity. It doesn’t matter if you’re in the art world or the beauty world — or journalism! Keep it pure.”

All of this pondering of the pure and the good led us back into philosophical pastures, where we stumbled upon the Indian, anti-colonial nationalist and ethicist Mahatma Gandhi’s remark, “I will not let anyone walk through my mind with their dirty feet.”

There is plenty to unpack there with regard to what it means to be able to think clearly — and cleanly, too? Anyone for purity of thought and of mind?

We were also reminded of a pronouncement by that great, 20th-century philosopher, Mae West, who seemed to understand the meaning of purity from various angles and as a result of some formative lessons learned in the School of Life.

“I used to be Snow White, but I drifted,” West once quipped.

That’s the kind of expression of profound self-awareness we can savor. It is at once honest, unabashedly authentic — and unmistakably pure.

Resources

Website of the artist Olivia Munroe

https://www.oliviamunroe.com/

Website of the artist Daisy Craddock

https://www.daisycraddock.com/

Instagram account: @daisycraddock

Website of the artist Stephanie Brody-Lederman

http://www.stephaniebrodylederman.com/

Instagram account: @stephbrodylederman

Website of Morgen Schick

https://morgenschick.com/

Instagram account: @morgenschick

Information about the Active Argan line of skin-care products can be found here:

https://activeargan.com/

These products may be purchased here:

https://www.hsn.com/shop/active-argan/21173%20?query=active%20argan&isSuggested=true&store=