INSIGHTS FROM SOME FIRSTHAND CREATORS AND OBSERVERS OF CONCEPTUAL ART

In conjunction with this month’s examination of the spirit, guiding aesthetic principles, and outlook of conceptual art, we checked in with several individuals who have worked in this genre or who have been closely involved with it over the years. Here is a basketful of their illuminating observations about this kind of strongly idea-driven art, which collectively demonstrate that its influence certainly has been enduring over the decades — and resonant, too.

Martha Wilson

Best known as the founding director of Franklin Furnace Archive, a former, downtown-Manhattan art center and, today, an online research archive and grant-giving source for artists, Martha Wilson is also an influential performance and visual artist. She is now the organization’s director emerita. Recently, Wilson shared these comments with us:

“Here’s a story about conceptual art: When I graduated from college in 1969, my boyfriend didn’t want to be drafted into the U.S. Army to fight in the Vietnam War, and our painting teacher had been hired away to teach at ‘the coolest art school in North America’ — the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Why, at that time, was it regarded as coolest art school in North America? Because it was inviting the leading conceptual artists of the day to visit the school and teach there, such artists as Vito Acconci, Joseph Beuys, Jan Dibbets, Dan Graham, Doug Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Peter Kubelka, Sol LeWitt, and Lawrence Weiner.

I was enrolled in the English literature program at Dalhousie University in Halifax but I hung out at NSCAD and even participated in some of David Askevold’s projects classes, in which, for example, Dan Graham took the students to the Halifax Citadel, a fort that was built in the 1700s, to film one of his projects.

Today, I’ve come to believe that all art is conceptual in that every work of art contains an animating idea, even if that idea concerns, say, just the surface of a painting. The catch is that most of the conceptual works being presented by the artists who were initially associated with the movement did not engage with issues in the real world. For example, Jan Dibbets once published an artist’s book about how he changed the outline of a bird’s feeding area in a public park by moving a bird feeder three feet every day. Well, that was fine, but really, who cares?

So I started making work about being a second-class citizen, using my woman’s body as my material. This work was encouraged by Vito Acconci, the only conceptual artist [in that early period] who regarded sexuality to be a legitimate subject for contemporary art.”

Harley Spiller

An inveterate collector of just about everything — scissors, restaurant menus, newsstand weights, magnets, chicken wishbones, Mr. T. memorabilia, and more — Harley Spiller is the current director of Franklin Furnace Archive. In the guise of “Inspector Collector,” he has shared his passion for collecting — the art of gathering and connoisseurship — with youngsters by addressing school groups. Spiller’s book Keep the Change: A Collector’s Tales of Lucky Pennies, Counterfeit C-Notes, and Other Curious Currency was published by Princeton Architectural Press in 2015.

Having worked alongside Martha Wilson at Franklin Furnace Archive for many years and now in his role as the organization’s director, Spiller has helped oversee the execution of performance-art presentations, exhibitions, and site-specific projects by artists from all over the world, many of whose creations have been influenced by conceptual art or could be categorized as examples of the genre.

He told brutjournal: “Over the past 30 months of the pandemic, I’ve been to precious few museums or galleries, and to no art fairs, but the shows that I have seen and the many I recall from ‘the before times’ did include hefty amounts of conceptual art. When it comes to assessing what makes for a good or bad work of conceptual art, I tend to ask: Does it resonate? Does it come back to mind well after I’ve witnessed the actual art? It doesn’t matter if it makes me smile or cry, or if it provokes any other emotion or visceral response. What counts is the art’s long-term impact.”

We asked Spiller if, after many years working closely with contemporary artists form around the world, he has come to expect a lot of new work to be influenced by, if not vivid examples of, conceptual art and its aesthetic principles.

He said, “Sorta, kinda. I don’t take for granted that that’s what I’ll see, but concepts seem integral to art, whether it’s a realistic painting or a minimalist endurance-type performance. Surely Soutine had a motivating concept in mind when he painted a side of beef all raw, red, and dripping with blood. Does that make such a painting any more or less conceptual than a work by such artists as, say, Lawrence Weiner, Sol LeWitt, John Baldessari, or Jenny Holzer? I prefer not to assign labels but rather to absorb and hope for resonance from a work of art. For me, that’s a mark of truly great art.”

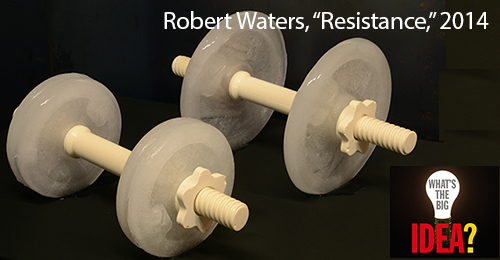

Robert Waters

Now based in the Basque Country of northwestern Spain, Robert Waters is a Canadian artist and teacher who has shown his work in Canada, Japan, and around Europe. When he lived n Mexico City in the early 2000s, he explored the rituals, beliefs, and symbols associated with Roman Catholicism in colonial and post-colonial Mexico. There, too, he made site-specific art installations using packing tape and taught blind people about the theories of the French modern artist — and conceptual art’s de facto patron saint — Marcel Duchamp.

A few years ago, at The Container, a contemporary-art venue in Tokyo, he showed silk-screened images of the doors of metal lockers, which, when pinned to the gallery’s walls, looked convincingly real. He also presented small barbells whose weights were frozen discs made from his own sweat. (They melted, of course.)

Weighing in on conceptual art, Waters said: “In general, I think that most artists use conceptual-art strategies to [distance] their work from established aesthetic traditions and to explore unknown creative directions. In part, this is a reaction against the recognized art movements that came before them, a form of critique. Principally, though, I think that most people create conceptual art with the goal of creating new ways of experiencing ideas about art, which in turn offer innovative ways of understanding ourselves.

Conceptual artworks are irreducibly aesthetic, no matter how anti-aesthetic their creators’ approaches might be. The anti-aesthetic aesthetic that is associated with conceptual-art strategies is a way of drawing attention toward the ideas on which such work is founded, including the context in which it functions. The aesthetic position of most conceptual artists holds that their art is better understood as a form of thought than as something material. Its significance is cognitive.”

Waters noted that his discovery and assimilation of conceptual art’s outlook and principles had a big effect on him. He said, “I somewhat relate losing my religion as a teenager to my experience coming to terms with conceptual artworks as a young artist. Questioning traditional ideas about art (such as the value of artistic authorship and craftsmanship) and discovering new ones (such as appropriative, participatory, and performative methods) were important steps that broadened my understanding of the potential of artistic expression and of the appreciation of art.”

The artist added, “But glimpsing the implicit freedom of artistic innovation didn’t mean that I stopped enjoying traditional artworks. I continue to appreciate technical mastery (that is, in aesthetic artworks) just as much as theoretical subversion (in conceptual artworks) when in comes to aesthetic experiences.”

Shai Ohayon

Having been based in Tokyo for more than a decade, Shai Ohayon was the founder of the above-cited contemporary-art gallery, The Container, which closed earlier this year. During its long run, the gallery showed quite a lot of conceptual art in a variety of genres and media, including photography and site-specific projects for which it presented documentation in different forms. A few years ago, for example, Ohayon showed the German artist Mischa Leinkauf’s video record of his treks through the sewer systems of several large cities around the world.

As an admirer of conceptual art who comprehends — and often savors — its unconventional, sometimes subversive attitudes and points of departure, Ohayon observed: “I don’t think of conceptual art in terms of visual aesthetic. It is true that many conceptual works also pay a lot of attention to the fabrication of the piece, but generally, I think that the essence of conceptual art is a deliberation of ideas. It’s the poetry of ideas and, yes, it can also have a specific structure, but not necessarily.

Many contemporary works rely on conceptual ideas or theories, but that doesn’t make them conceptual works but rather works with [some] concept. In conceptual works (and in the theory of conceptual art) the concept is at the forefront.

Many types of art are intangible, like some environmental works, ephemeral works, performance art, and a lot of digital work; just look at the rise of art made in the metaverse and the hype surrounding NFTs. Art doesn’t need to be tangible to be art, and much of conceptual art isn’t tangible, and that’s fine.

For me, artistic expression takes many forms and doesn’t always need to rely on technical skills. My view is that technical skills are something one can train oneself to acquire, while ingenious ideas, the core of creativity, are the foundation for the production of art. The artist is a spy who uses his or her observations to poetically share ideas or notions. What I love about a lot of conceptual art is that creating it takes a lot of dedication [on the part of an artist], with planning and other activities that sometimes take place over long periods of time. For me, such an artist’s persistence and consistency are very admirable, as I’m not so good with that. Time-based projects especially fascinate me.

Throughout human history, art always has challenged perceptions and social constructs, and, with this in mind, conceptual art is no different. Good conceptual art, like all good art, is a creation embedded with truth and a genuine reflection about aspects of life, society, or the self. Bad conceptual art is, like all bad art, contrived.”