Phillip March Jones, the founder of Institute 193 in Lexington, Kentucky, and now the founder and director of the new March Gallery in New York, is one of the best-known researchers and curators in the Unted States specializing in the work of self-taught artists from the American South.

The exhibitions he has assembled, such as a first-ever survey of the work of the African American artist Charles Williams (1942-1998), a visionary Afrofuturist, which was presented last year at the Atlanta Contemporary, have greatly expanded our understanding of the ideas and achievements of some of the 20th century’s most original autodidacts.

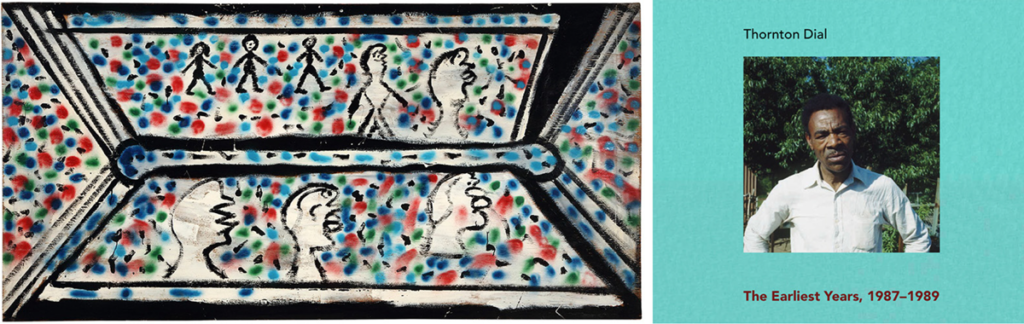

Now, representing March Gallery and teaming up with Sam Parker Gallery in Los Angeles, Jones has tapped exclusive sources to put together Thornton Dial: The Earliest Years, 1987-1989, Parker’s presentation of some of the very first paintings on board and mixed-media metal sculptures that Dial, a former welder at a Pullman railway-carriage factory in his native Alabama, created at the very start of his art-making career.

In the Los Angeles gallery exhibition’s accompanying catalog, Jones writes:

In the late summer of 1987, Lonnie Holley brought his friend, the collector William S. Arnett, to visit the home [in rural Alabama] of Thornton Dial, Sr., an event that would change the course of their lives. Holley, an artist and seeker of like minds, had met Dial at the introduction of a former girl-friend and had acquired several of his handmade fishing lures, which hung on a wall in his home.

Upon seeing them, Arnett suggested a visit. The two men, in conversation with Dial, found him to be somewhat guarded, and it became clear that he didn’t know or acknowledge their concept of “art.” For the purpose of demonstration, Arnett asked Holley to make an artwork. Holley then created a pocket-size wire sculpture of a woman’s profile that included a metal ring, some turkey feathers, and a discarded, mass-produced fishing lure, all found outside.

Dial’s response to this impromptu creative exercise was: “If that’s art, then I’m going to show you some art.” Over the next few years, he made good on his promise.

This moment marks the beginning of the impossibly inventive first stage of Dial’s career as an artist, a period characterized by rapid innovation, material exploration, and self-discovery. The earliest works in this publication rely on the artist’s experience as a fabricator. With his children, Dial had a small furniture business and in the weeks that followed his meeting with Holley and Arnett, Dial transformed chairs, plant stands, concrete sidewalk liners, and other utilitarian objects into sculptures.

As time went by, he began using more traditional materials, creating two-dimensional paintings and assemblages that explored cultural-origin stories, religious mysteries, family dynamics, racial tensions, and the problematic socioeconomic realities of modern American life, among other subjects.

Thornton Dial: The Earliest Years: 1987-1989

June 6 – July 31, 2021

Sam Parker Gallery

2441 Glendower Avenue

Los Angeles CA 90027

www.parkergallery.com