THE SWISS ART BRUT CREATOR ARMAND SCHULTHESS PLACED HIS WORKS OUTDOORS, IN SYMBIOSIS WITH NATURE

by Edward M. Gómez

Le jardin de la mémoire, by Lucienne Peiry (Paris: Éditions Allia, 2021, ISBN 979-10-304-1543-8)

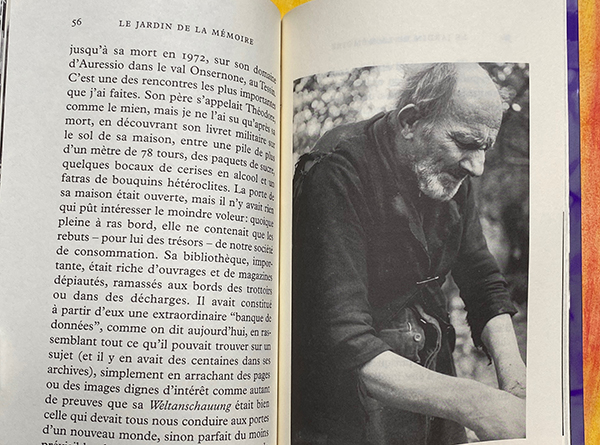

Armand Schulthess (1901-1972) was a Swiss self-taught artist who was born André Fernand Armand Thüring in Neuchâtel, a canton situated on the western bank of the lake of the same name in southwestern Switzerland, and who, later in life, created one of the most remarkable, site-specific art environments in the annals of art brut.

Now, in her newest small monograph, Le jardin de la mémoire (The Garden of Memory, published by Éditions Allia, Paris), the Swiss art historian Lucienne Peiry, a well-known specialist in the art brut field who is a former director of the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, and the author of numerous important books and curator of notable exhibitions in her specialized subject area, examines Schulthess’s life and oeuvre with insight and deep appreciation for his distinctive vision.

A year after Schulthess was born, his father died. His mother remarried, and her new husband adopted her infant son, who took his stepfather’s surname. Later, the boy would become known as “Armand.” Peiry recalls how Schulthess acquired an education and pursued the professional path of a conventional, respectable bourgeois businessman.

He attended a commercial college and became an apprentice in an import-export company; later, starting in the early 1920s, he operated a firm that produced women’s clothing. Ultimately, his experience in the business world led him to a government-bureaucrat’s job in the offices of the Swiss Federal Department of Public Economy in Bern, Switzerland’s quiet capital city, which is located in the central, German-speaking region of the country.

There, Peiry, notes, Schulthess’s coworkers described him as “unassuming, quiet, and shy,” and as possessing a “humble and modest” attitude. He was not someone who rocked the boat or called attention to himself.

In fact, Schulthess’s reserve masked some rather bold, big ambitions. As Peiry writes in Le jardin de la mémoire, which has been published in French, her native language:

“At the age of 50, in 1901, the unmarried functionary decided to cut loose from his moorings and set sail. He renounced his well-established social status and comfortable professional situation, setting off to install himself in the remote border area of Switzerland, on a property in Ticino he had acquired some ten years earlier in Auressio, a little village situated above Locarno in the Onsernone Valley.” [Italian-speaking Ticino is Switzerland’s southernmost canton. It is bordered by Italy to the west, south, and east.]

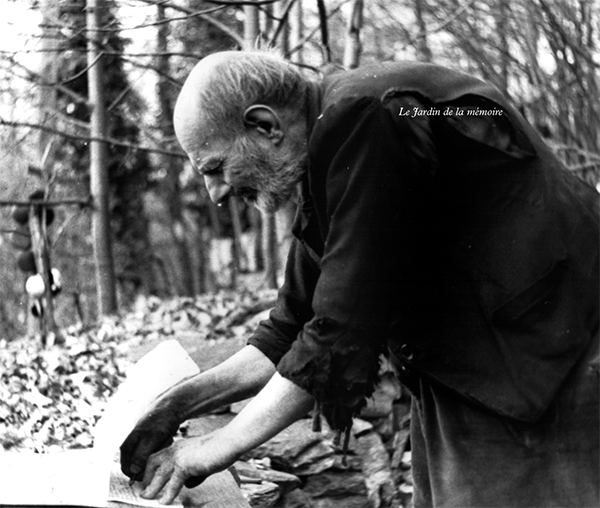

There, Peiry writes, Schulthess was able to “establish a direct contact with nature, which renewed itself with the cycle of the seasons in a climate marked by particularly nuanced contrasts.” In the Ticino backwoods, Schulthess transformed his roughly 4.5-acre property into a permanent art installation in which nature itself — the trees, the weather, the light, the texture of the hilly terrain — served as one of his main materials.

His land became the setting for an expansive kind of text-based work in which Schulthess attempted to bring the vastness and the diversity of human knowledge out into nature by literally displaying handwritten plaques and signs expressing a wide range of ideas, statements, questions, and historical facts.

Peiry reveals in her text that, prior to leaving Bern, Schulthess had amassed a collection of books and magazines, as well as more than 70 scrapbooks that he had put together himself during the 1930s and the 1940s. Those albums contained, she notes, “the necessary documents for his feverish project,” which he had “carefully assembled” — hundreds of pages of reference material that he had cut and pasted from magazines or brochures, as well as information from assorted other sources Schulthess had copied out by hand, including “articles, essays, definitions, excerpts, and references [for which he] made use of makeshift materials — found papers, tissue paper, tracing paper, and reflective metallic paper.” Schulthess made lists filled with numbers and words, drawings, and tracings.

In time, Peiry explains, Schulthess would give this material “sculptural” and, eventually, “environmental” form, as he transferred the information, knowledge, and ideas from his reference archive onto small sheet-metal plaques that he painted himself. Their countless declarations, statements, and questions formed a kind of free-floating expression of human inquiry out across the landscape, for the artist hung his signs from tree branches or nailed them to the trunks of trees.

Long before the contemporary American artist Jenny Holzer proclaimed her punchy “Truisms” in the form of colorful printed posters, or her American peer Barbara Kruger employed in-your-face, propaganda-like graphics to deliver provocative slogans questioning the social-political status quo, Schulthess, who spoke several languages and was something of a polymath, took his message of intellectual, artistic, and spiritual inquiry directly from his human heart and mind out into the living, ever-changing laboratory of nature.

In various languages, Schulthess’s posted plaques offered such statements or invitations as:

“I idea: sit and read a book”

“during the vacation periods and here, in the middle of Nature, polish [your] studies of metaphysics, philosophy, psychology, or [your] scientific or mathematical studies, or [your study] of the law” [and the list goes on to cover a vast range of subject areas]

“please telephone me this evening at 98 8 01 78”

“in case I’m not here: please slip a little note in the crack beneath the door with your address and I’ll stop by”

His plaques called attention to many different books, such as, for example, The War of the Worlds, the British author H.G. Wells’s science-fiction tale from the late 1800s, and noted that Schulthess had copies of that novel available in his home in English and in French. They informed passersby that he owned audio-recording and camera equipment, just in case anyone might want to stop by and create an audio-visual work of their own.

His signs quoted or referred to many other artists, scientists, thinkers, or historical figures, too. On one, he cited the 19th-century French psychologist and pharmacist Émile Coué, who became known for proposing a method of self-improvement based on optimistic “autosuggestion.” On his plaque, Schulthess wrote: “Emil Coué 1857-1926 created autosuggestion: every day and from all points of view, I’m getting better and better.”

Looking back at Schulthess’s achievement, Peiry describes his site-specific creation by noting:

“This poetic labyrinth constituted an act of symbolic resistance. In the greatest solitude and with unwavering determination, the former functionary attempted to reorganize the cosmos and reorder human thought. In creating his garden of memory, he allowed knowledge and nature to enter into symbiosis in a work that, ultimately, was ephemeral.”

The story of Schulthess’s quietly eloquent oeuvre does not have a happy ending. In the final pages of her book, Peiry recalls:

“One morning in 1972, the old man was found, lifeless, in his garden, dead due to the cold or [perhaps] to a fall from a high rock. The following year, in an iconoclastic gesture, authorities in Ticino and Armand Schulthess’s heirs emptied out his house, and burned and destroyed his artwork.”

Fortunately, however, several well-known figures in Switzerland’s art world of that era were able to intervene in time to save a certain quantity of the artist’s creations, a notable number of which can be found today in the permanent holdings of the Collection de l’Art Brut, the well-known museum in Lausanne.

Peiry describes Schulthess’s grand effort to evoke human knowledge in a natural setting as a kind of “splendid incantation,” which, today, sadly, has disappeared. His “garden of knowledge,” she observes, “still resonates as an unfinished list” of all that is known or that can be explored and learned, a compendium of knowledge that “is forever open” to being completed.

Thanks to Peiry’s informative, lucidly written book, one that deserves to be translated into and published in English so that it may reach a wide, international audience, Schulthess’s legacy will endure. In its pages, she honors, too, the courage with which the Swiss créateur left one life to begin another, all in pursuit of his artistic dream.

Resources

Website of Éditions Allia, where Lucienne Peiry’s new book, Le jardin de la mémoire, may be found:

https://www.editions-allia.com/fr/livre/925/le-jardin-de-la-memoire