AN ARTIST TRACES HIS CREATIVE PATH, FROM CHILDHOOD, OUT-OF-BODY EXPERIENCES TO THE MAKING OF FAR-OUT CONTEMPORARY ART

Fumio Shiozawa is a Japanese self-taught painter who keeps studios both in Shizuoka Prefecture, a coastal region located to the south-southwest of Tokyo, and in the tranquil city of Kyoto, Japan’s former capital, where well-preserved, elegant Shintō shrines and Buddhist temples abound.

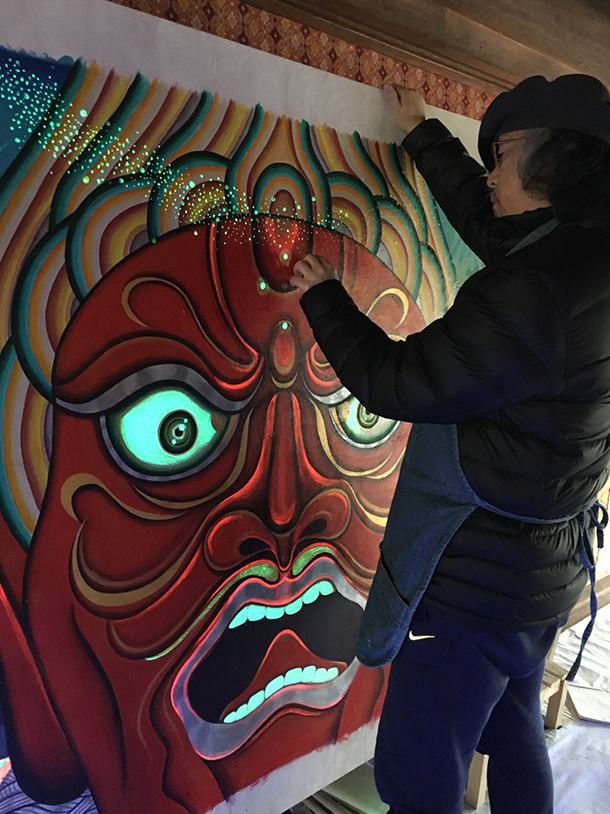

In recent years, Shiozawa has exhibited his paintings within the usually off-limits rooms of some of Kyoto’s most famous and venerable temples. He has an exhibition at a Buddhist temple in Tokyo coming up toward the end of this year and he is working on a big painting that he will display and also donate to the Mahabodhi Temple complex in India at the end of next year.

Earlier in his career, as a designer and illustrator, Shiozawa created a poster for the musician Sting’s “Save the Rainforest” campaign; he also helped produce books by such Japanese authors as the rock musician Kazufumi Miyazawa, the modern artist Tarō Okamoto, the contemporary photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, and the artist and illustrator Seizō Tashima.

Recently, brutjournal’s editor in chief, Edward M. Gómez, met Shiozawa and his studio manager, Masako Koruge, in Tokyo, where they discussed his Buddhism-influenced spiritual outlook and the art it has inspired. Often, Shiozawa’s images are bold, brightly colored, and assertive; they’re definitely not the more reserved, whispering kinds of pictures that come to mind when one thinks of certain traditional forms of religious art.

We’re excited to be able to introduce Shiozawa’s work now, in the context of brutjournal’s special package of articles looking at the spiritual in art, the spirit world, and art and spirituality. The website of the artist’s studio, which is called “Wild Einstein,” can be found here.

The artist’s remarks have been translated from Japanese into English by Edward M. Gómez.

brutjournal: Tell us a bit about your background — when and where were you born, and where did you grow up? Did your parents or other relatives, or people around you in school make art? Were they interested in it and, if so, did they influence you as a youngster?

Fumio Shiozawa: I was born in 1955 in the Kita-Senju district of northeastern Tokyo and I grew up in the neighboring Saitama Prefecture. As far as art-related influences are concerned, there were none from my family members or the people around me when I was growing up. As an artist, I’m completely self-taught. I never received any kind of academic or specialized instruction with regard to making art.

brutjournal: Over the years, how and where did you develop an interest in art, discover your art-making techniques, and begin producing art yourself?

Fumio Shiozawa: When I was a young boy, one of my classmates died by drowning in a river. I was an eccentric child; at that time, [as a memorial for my classmate,] I made a Buddha sculpture out of the river clay and set it off in a boat. I liked to draw and make things with my hands, but because I could never could get accustomed to making the ordinary kinds of artworks proposed by the school’s art prigram, my teacher asked, with worry, “Is there any problem at home?” — and even went so far as to occasionally call my parents.

When I was 16 years old, I watched a BBC drama about the life of Leonardo da Vinci. I was so painfully moved by it that I vowed that, in the future, I would become an artist like da Vinci. Sometime later, I bought a DVD of that program, and even as an adult, I went back and watched it many times.

My life as a designer began when I was in my twenties, and I worked right up until I was managing a design office. In 1986, I read an interview with Tarō Okamoto in the magazine Studio Voice, and for his kind of nonconformist art I felt such a yearning that I recognized that, somehow or other, I would undertake such an artistic endeavor myself.

[Editor’s note: Tarō Okamoto (1911-1996), one of Japan’s most prolific and influential modern artists, made paintings, sculptures, and works in other genres; he also published many writings about art and aesthetics, and conducted extensive research on the ancient historical roots of Japan’s artistic traditions.]

That same year, 1986, a program about the artist Isson Tanaka [1908-1977], who lived and worked in the Amami Islands in the far south of Japan, was broadcast on NHK-TV’s Sunday art program.

In his painting style, the fullness of the Nihonga mode of painting can be seen and felt. [Nihonga painting uses certain traditional Japanese materials but often employs Western techniques to depict familiar subjects related to Japan’s culture and history.]

I started traveling frequently to the Amami Islands. In these remote islands, I was deeply moved by the relationships between nature and the cosmos, and the gods of Shintō [Japan’s indigenous animistic religion] and Buddhism. I made many sketches and, later, my thinking about these topics influenced my production of paintings.

One day, in the Amami Islands, I took part in a senkotsu ceremony [the washing of cremated bones before placing them in a funerary urn; in this case, 15 years after the deceased person’s death, the bones were disinterred and cleansed]. On that day, entering the ocean was prohibited on account of sea snakes that could attack you and wrap themselves around your neck; what a profoundly mysterious experience!

It was such a peculiar occurrence that, for a while, no one uttered a word, but Toshiko Okamoto, the late artist’s partner and private secretary, spoke up and said, “This is mythological! It’s absolutely something left over from ancient myths! I will write something about this. You must paint this, please!”

With those pointed words, our book, Kaishin no hime (Divine Sea Princess, published by Kōsei Shuppansha in 2003) was born, with a text by Toshiko Okamoto and pictures by myself. Ever since that time, I’ve come to believe that my art has been the fruit not only of such coincidences — just simple ideas — but also of my personal experiences and imagination. As an artist, it’s as though I’ve immersed myself in the creation of works that possess a certain mystique.

brutjournal: Earlier in your career, what did your works look like? Did you make more figurative or more abstract works?

Fumio Shiozawa: When I was a designer, I drew in a manner that was concrete or abstract, but compared to my work as a painter, that kind of work was too lacking in fire. Following my experiences in the Amami Islands, I became interested in Japan’s climate and natural features, and I changed and started to cultivate an aesthetic sense related to nature in Japan and to the cosmos.

brutjournal: Approximately when did you start developing what may be called your mature style, examples of which can be seen in the photos illustrating this magazine article?

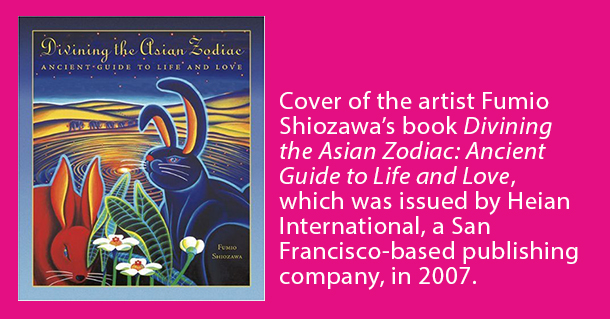

Fumio Shiozawa: In 2007, Heian International, a publishing company in San Francisco, asked me to work on the book Divining the Asian Zodiac: Ancient Guide to Life and Love. At that time, as I studied world mythology and ideas about the supernatural, gradually my style began to come together and take shape.

brutjournal: You’re interested in spiritual themes, and your work reflects this interest. Tell us a bit about this interest of yours, especially with regard to your study of, interest in, and influences from Buddhism.

Fumio Shiozawa: With regard to Buddhism, my grandmother, who was a fervent believer in the power of the Lotus Sutra and strived to achieve a state of spiritual equilibrium — I’d say that, looking back on my childhood, my Buddhism-related experiences really began around that time.

When I was a child, my body was weak, and often I had high fevers. Many times, with my body feeling as though it were suspended, I had out-of-body experiences. I believe that my interest in mystical ways of thinking and incidents may be rooted in my own personal experiences.

brutjournal: In recent years, you have exhibited your paintings at ancient Buddhist temples in Kyoto. Tell us how these unique exhibition opportunities came about.

Fumio Shiozawa: In 2016, without any particular objective in mind, I set up a new studio in Kyoto, and an opportunity to show my work fortuitously arose. At that time, while I was speaking with a Buddhist monk, he suggested that I create a large-format painting on the theme of the Lotus Sutra. (See my painting from 2018, which depicts Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha, and also what are known as the Four Heavenly Kings.) Prior to that time, I had never painted any Buddhist imagery and I felt a bit lost at sea, but having my childhood mystical experiences and the Lotus Sutra to rely on, I undertook the assignment.

brutjournal: Tell us about the exhibition of your paintings that is scheduled to take place at a temple in Tokyo later this year, in December.

Fumio Shiozawa: My plan is to complete a painting of the Buddhist priest Nichiren experiencing satori — enlightenment — for display at Daibōhongyōji, a temple in Tokyo’s Ikegami Ward, around the beginning of December. The exact dates of this exhibition will be announced in the near future. If many people come to see and appreciate it, I’ll be very happy!

brutjournal: You’re working on another big project, this one for a special venue in India.

Fumio Shiozawa: I will present my painting of Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha, experiencing satori, next year, on December 8, 2023, in the main temple of the Mahabodhi Temple complex, a UNESCO World Heritage site in eastern India.

I really do believe in Buddhism’s message — that we can create a world of love, harmony, and compassion. Perhaps this news may grab the attention of some of the many people who are always running around. I’m hoping to create a work of a kind that may mark a new dawn for [the spreading of the teachings of] Buddhism.