AT THE NORTON SIMON MUSEUM: 25 TINY WORKS BY SOME OF MODERN ART’S BIGGEST NAMES

Modernism in Miniature

August 12, 2022 – January 9, 2023

Norton Simon Museum

411 West Colorado Boulevard

Pasadena, California 91105

Exhibition organized by Frances Lazare

by Sarah Fensom, brutjournal’s U.S.A. West Coast bureau chief

At the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, northeast of central Los Angeles, the exhibition Modernism in Miniature is on view in a small, square gallery located to the right of the admissions desk. There, displayed on walls that have been painted a deep shade of navy blue, are 25 works from the museum’s collection dating from the early to mid-20th century. Arranged chronologically, they span a range of modern-art styles and movements, from German Expressionism to American Pop.

Among the big-name modernists whose works, in this unusual presentation, can be seen playing it small: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Lyonel Feininger, Joseph Cornell, Claes Oldenburg, and John Chamberlain.

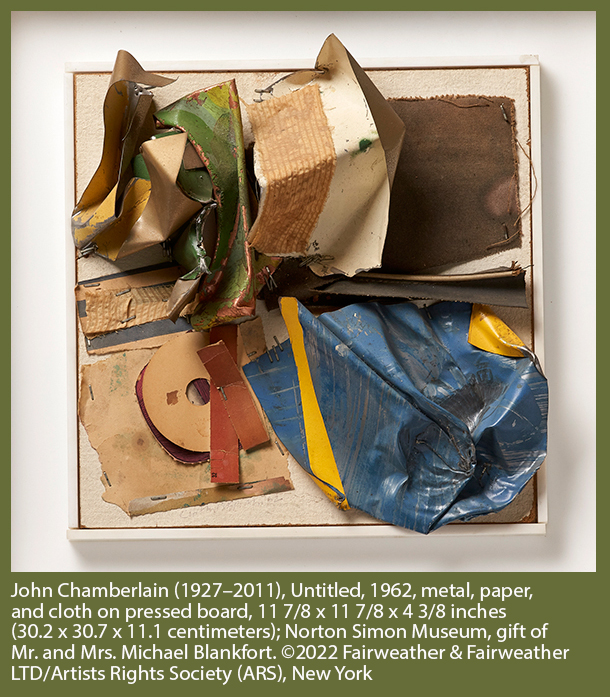

Despite the exhibition’s provocative title, to describe each of the pieces on view as teeny-tiny would be inaccurate. That’s because, although all the artworks it presents are quite small, in a number of cases, they may be seen as reduced in scale relative to the proportions in which the featured artists here were known to have more typically worked; for example, a John Chamberlain piece on view measures roughly 12 by 12 inches and is microscopic compared to the large-scale, crushed-metal sculptures for which this artist is well known.

In other instances, the works on view are about scale; in different ways, they communicate something about size or fit, or about how certain compositional elements function together, as in “Collection of Small Pictures,” a poster-size Picasso lithograph illustrating tiny, framed works hung together on a museum wall. Overall, the exhibition reveals how, in the right circumstances, an artwork’s meaning may become stronger and richer as its size decreases.

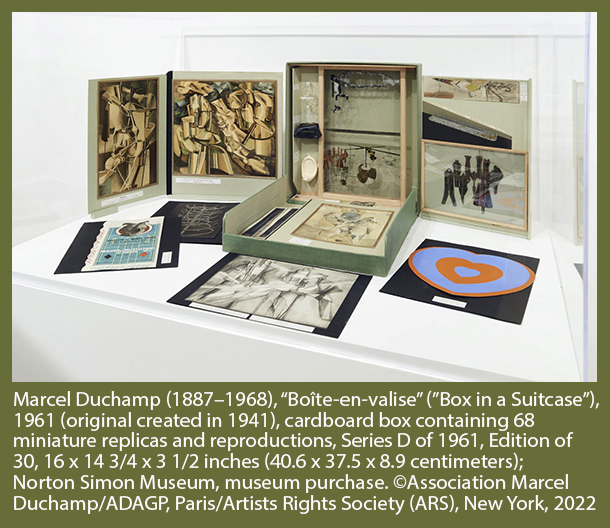

Marcel Duchamp’s well-known “Boîte-en-valise” (“Box in a Suitcase”) appears in the center of the gallery. A container serving as a “portable museum,” it features 68 small scale-reproductions of the artist’s early paintings and “readymades,” including tiny versions of such works as “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2” (1912), “Bottle Rack”(1914), “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even”(1915-1923), “Fountain”(1917), and “L.H.O.O.Q.”(1919), which he created between 1935 and 1941. The version of “Boîte-en-valise” that occupies pride of place in the current exhibition comes from the Norton Simon’s own collection and was produced in 1961.

This Duchamp’s work is packed with layers of meaning that extend beyond the many visual and philosophical ideas that are conveyed by the artist’s individual works. For example, this portable container resembles a mid-20th-century salesman’s sample case, playfully positioning his petite reproductions of his own artworks in a manner in which they could have been presented as models to prospective customers. With his suitcase filled with mini-art, Duchamp slyly acknowledged the differences — and similarities — between fine art and commercial products as salable commodities.

Together, the miniatures in “Boîte-en-valise” can also be seen as forming a sort of flea-circus-size Duchamp retrospective. The unboxed container, with its tiny parts, resembles a toy set but it also brings to mind European Kunst- und Wunderkammer of the 16th and 17th centuries —display cabinets filled with art and curiosities that were the predecessors of modern museums.

The display of the other works in the exhibition begins with two small, oil-paint-on-wood sculptures, both titled “Head,” made by the German-American artist Lyonel Feininger in 1920. They are accompanied by a third sculpture created by Feininger’s son, T. Lux, in 1923, when he was around 13 years old. Taking the form of heads, the sculptures’ figural qualities emerge from small blocks of wood in sharp, angular cuts. Carving small figures was a hobby Lyonel Feininger pursued as a boy, when he made his own toys. He was fascinated by model trains and eventually created “Toy Town,”a small-scale city complete with hand-carved railways, houses, and yachts.

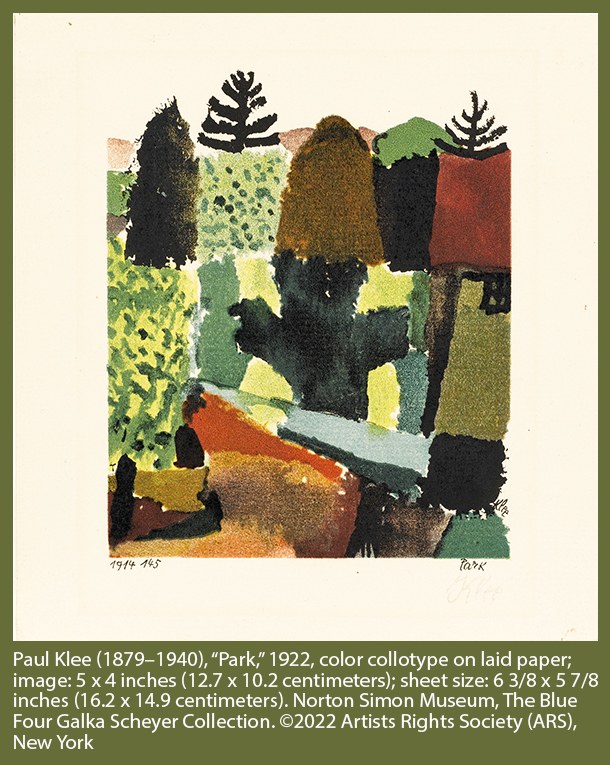

Vasily Kandinsky’s “Small Worlds X” (1922, drypoint on heavy wove paper) appears in a group of wall-mounted works on paper created in the 1920 and 1930s. Somewhat on the larger side of “small” at 9 3/8 by 7 3/4 inches (23.82 x 19.7 centimeters), it practically dwarfs Paul Klee’s luminously colored “Park” (1920, color collotype on laid paper) and Alexei Jawlensky’s “Small Abstract Head: Red-Black” (1928, watercolor, oil, metallic paint and pencil on wove paper).

A close look at “Small Worlds X” reveals why it is one of the exhibition’s key pieces. This self-contained cosmos is made up of a seemingly endless number of minuscule gestures, with clusters of abstract forms consisting of the tiniest lines, dots, flecks, and geometric shapes. Each mark is fine and purposeful, making the whole composition all the more potent. “Small Worlds X” was part of a portfolio, “Small Worlds,” which Kandinsky published in 1922, shortly after he began teaching at the Bauhaus in Germany.

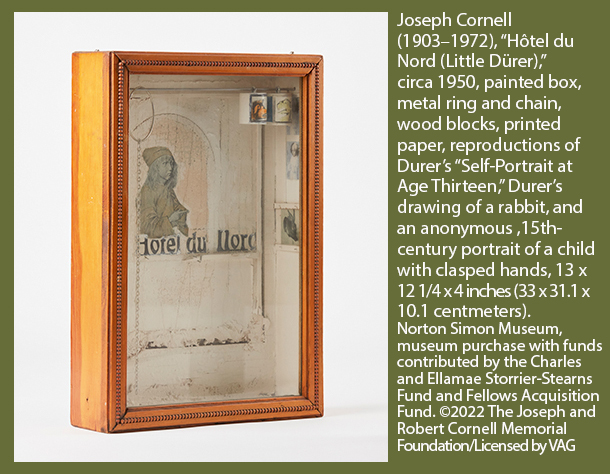

Another standout here is Joseph Cornell’s “Hôtel du Nord (Little Dürer),” one of the enigmatic American artist’s shadowbox assemblages from around 1950 that was part of a series of small “museum” boxes he began making in the late 1940s. Cornell called these pieces “musées des poches,” or pocket museums, echoing Duchamp’s view of his “Boîte-en-valise.”

This particular “pocket museum” of Cornell’s, dedicated to Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), contains a reproduction of the great, German-Renaissance printmaker’s “Self-Portrait at Age Thirteen” as well as the young virtuoso’s masterful drawing of a rabbit. Its subject matter also includes an anonymous, 15th-century portrait of a child with clasped hands, a metal chain, and two images of a boar and a griffin adhered to wooden blocks.

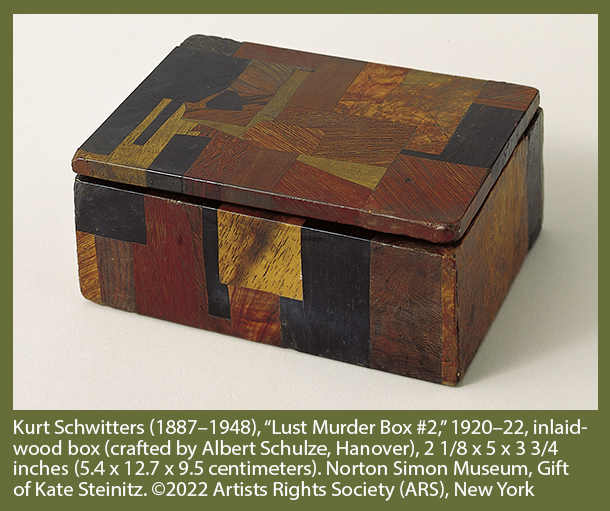

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Kurt Schwitters’ “Lust Murder Box No. 2” (1920-22, inlaid wood box) also addresses notions of collecting and containment, albeit in a more sinister — and playful? — manner. The German artist designed the palm-sized box with Albert Schulze, a cabinet-maker and master of wood mosaics, to resemble Schwitters’ large-scale collages and installation works. Although the Schwitters work on display in the current Norton Simon exhibition is empty, some of this artist’s other boxes contain dismembered doll parts (which refer to some grizzly murders that took place in Hanover, Germany, in the 1920s, seizing the public’s attention).

The contemporary artist Richard Pettibone’s “Roy Lichtenstein, ‘Picasso’s Woman with Flowered Hat,’ 1963” (1970, silkscreen on canvas) links the themes of miniaturization and reproduction. Here, Pettibone reproduces and scales down the pop artist Lichtenstein’s 1963 scaled-up, Ben Day dot version of Pablo Picasso’s “Woman with Flowered Hat” (1941), a portrait of his lover, Dora Maar.

By rendering Lichtenstein’s enlarged version of Picasso’s work in miniature, Pettibone continues a conversation about authorship — and modern-art history — that Lichtenstein’s work ignited. But Pettibone’s mini-replica of an interpretive copy of Picasso’s painting emphasizes the nature of the source artwork as an object; it feels less grand and less out of reach than that original. Pettibone’s creation feels more like a trinket, not unlike a miniature version of the Empire State Building purchased in a New York City souvenir shop.

Still, the fact that Pettibone’s subject matter merited its transformation into a pocket-size object, like the iconic skyscraper or any other major work of art or architecture that becomes a tote-bag decoration or collectible tchotchke, also reflects its cultural importance.

The Norton Simon Museum’s promotional materials for Modernism in Miniature point out that the exhibition is being presented in its most intimate-feeling gallery and also that its unconventional — and maybe somewhat unexpected — content may be seen as “reveal[ing] a counter-history of 20th-century art,” one in which, in the face of the demands imposed by modern art, as it evolved, for “increasing monumentality,” a “tradition of whimsy, play, and intimacy” still thrived and endured.

This is a very interesting discovery, to be sure, and given the bombast and big sizes that characterize certain examples of now-classic, high modernism, it’s also no small thing.