NOW, MORE THAN EVER, CAN — OR SHOULD — NATURE SERVE AS AN ESSENTIAL POINT OF REFERENCE FOR ARTISTS?

By Edward M. Gómez

It’s no secret that the weary planet we humans inhabit and that, for centuries, but especially in modern times, we’ve been destroying with industrial pollution, wasteful ways of exploiting its natural resources, and an ever-expanding population is now deeply damaged and suffering — and that, in dramatic shows of force, from super-storms, life-choking droughts, wipe-out wildfires, and unstoppable floods, nature has begun striking back.

The spirit of the real-world, catastrophic “weather events,” as the news media call them, that have caused so much harm in different parts of the world in recent years is much different from that of, say, the tranquil vistas of mountains and valleys depicted in the monumental canvases of Thomas Cole, Albert Bierstadt, and other painters of the 19th-century Hudson River School. Those panoramic pictures portrayed such features of nature as repositories of mighty natural energies, all contained within a logical, divine order — that of nature — whose bountiful wonders were to be admired — and honored — with awe.

Today, hikers in many parts of the world cannot avoid stepping over soft-drink bottles on many a trail or encountering snack-food wrappers in the wild grass. And let’s not even get started on plastic pollution in the Earth’s oceans and rivers.

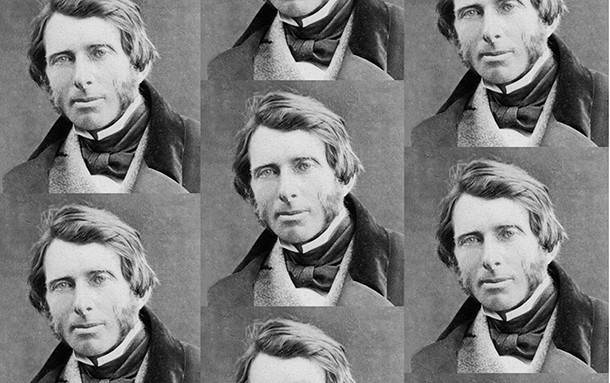

John Ruskin (1819-1900), the Victorian-era art critic and aesthete, philosopher, educator, and social-reform advocate, would have railed against everyday, thoughtless polluters had he lived to find plastic bags caught in tree branches or rotting flip-flops washing up on a beach.

Sounding like Charlie Brown after a session with a spiritual healer, Ruskin, who believed that, day after day, nature paints “pictures of infinite beauty,” also once opined, “There is really no such thing as bad weather, only different kinds of good weather.”

Sounding like good Buddhist, too, not the son of a wine importer in Scotland, he noted that “sunshine is delicious,” and “that rain is refreshing,” while the wind “braces us up,” and “snow is exhilarating.” (Never mind that some of us would rather skip the slopes and revel instead in the pleasures of après-ski, where we can do our best thinking.)

Ruskin believed not only that nature could serve as the essential starting point and all-around, all-purpose, never-fail, always-reliable reference point for artists but also that it should serve such purposes, and that, conversely, artists should realize that, as the opposite of — and antidote to — civilization, nature was the greatest artist. In matters aesthetic, it could do no wrong. Nature offered a textbook’s encyclopedic range of paragons of color, form, and texture, so, in it, what was there to ignore, dismiss — or disrespect?

In art, of course, as in science, nature is so big and multifaceted a subject, it would be impossible to out-Ruskin Ruskin by trying to depict it all, in all its variety and complexity. Here on Earth, some artists settle for — and investigate and analyze with wonder and aplomb — nature’s riches in the form of still-life pictures or landscapes; far beyond the ground beneath our feet, inestimably powerful, human-made contraptions like NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope are now using photography to produce images of nature’s unfathomable vastness in the depths of outer space.

Given the often cynical-feeling, ironic detachment that is the de rigueur outlook — or pose — of postmodernist critical theory, and the emphasis it places on de-emphasizing craftsmanship, technical proficiency, and the individual authorship of works of art, not to mention its general impatience with a concern as outmoded and stuffy as beauty (which, for some aesthetes, is never too far removed from truth), just what is the status of more traditional, more conventional art genres that take aspects of nature as their subjects?

Conversely, isn’t it interesting how today’s environmental crises, from global warming and global climate change to an alarming lack of drinking water in some places, among countless other urgent concerns, have seized the attention of so many contemporary artists?

If Picasso were alive today, would he still be knocking out pictures of his lovers with faces resembling smashed Coke cans or would he dare to produce a sweeping group of canvases like those of the indefatigable, Bosnian-born painter Amer Kobaslija, who created a form of contemporary history painting in the years following the earthquake and tsunami that took place in Japan in March 2011 with his series “One Hundred Views of Kesennuma”? Kobaslija’s subject in those impressive paintings was the raw power of nature itself.

Checking in with some artists in the brutjournal community, we asked them if or how nature might influence or inform their thinking about art or their art-making.

The artist Lisa Remeny, who lives and works in Coconut Grove, just south of central Miami, said, “Nature is and has been my muse for as long as I can remember. It’s everything to me; it’s pure and unfettered by human greed, asking nothing of anyone.” Remeny, who, in the past, lived in Jamaica and has traveled widely throughout the Caribbean, often makes the region’s flora and natural light the subjects of her oil-on-canvas paintings and watercolors on paper.

She observed, “Attempting to replicate the natural world in two-dimensional form is the challenge that makes me get up in the morning and hit the studio. I see art as my salvation, a reminder to be grateful for the beauty that can be found in everyday life. Even when I’m visiting a major city, it’s the skies and bits of natural beauty that I tend to focus on.”

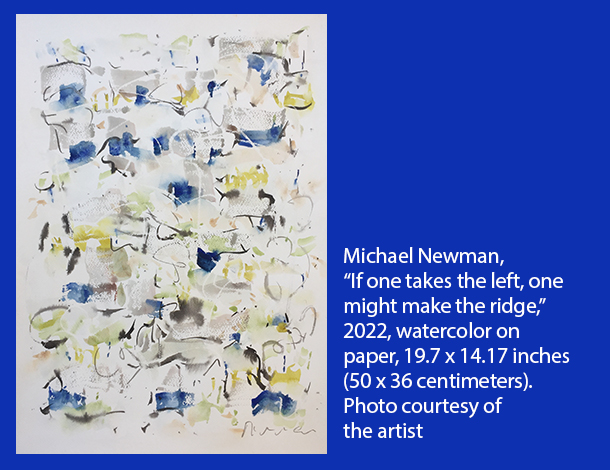

brutjournal readers will remember hearing in past issues from the American artist Michael Newman, who now lives, as he did more than two decades ago, in Taiwan. Having lived and worked, too, for many years in Japan, Newman long ago developed a painting technique that blends the disciplined spontaneity of East Asian calligraphic ink-wash painting with the rhythms and impulses of Western modern art’s gestural abstraction. The formal language he has refined imbues mere wisps of transparent color with the heft of sculptural forms. Newman’s recent paintings on Taiwanese handmade paper seem to provide him with a tonic for these soul-crushing times.

He told us: “Over the centuries, art has communicated various thoughts and ideas that were reflective of their times, and nature was often right there in it, as a backdrop for the ideas artists wished to convey. For me, art and nature are in constant communication with humanity. How we regard and define nature — in the wind, the snow, the oceans, one’s personal growth, the touch of a hand or a leaf — connects us to it and to each other. I’ve been watching my students at a university here in eastern Taiwan. They’re interested in nature, but why or how can it or should it affect them? For some, this seem to be a big question. Like many people, at least for now, as young artists, they might not realize the strength of the connections between us humans that nature can foster and the effects such connections can have on us.”

Finally, after admiring some recent still lifes made by the artist Mark Milroy, who is based in New York and teaches portrait painting at the National Arts Club there, we asked him about what had attracted him to a humble potted plant whose “portrait” he had painted several times.

These new pictures seem to revel in the physical textures of both their subject’s broad, luminous leaves and that of Milroy’s paint, which he applies in patches of color that combine to construct their verdant forms. For Milroy, who is primarily a portraitist, we wanted to know: What is his artistic connection to nature, and, through it, has he gained any insights that have informed his art?

Milroy replied, “As I mature as an artist, working from life, either with a person or a plant as my model, has become increasingly important to me. For, you see, in whichever kind I choose, there is a whole universe of shape, form, and color that appears, and if you spend enough time, it becomes animated. I certainly don’t hate plants, but as Georgia O’Keeffe once said, ‘They are cheaper than models and they don’t move.’”

There is a Ruskinesque nugget of wisdom buried somewhere in Milroy’s comment, and we’re determined to dig it out.