THE WORK OF A CONTEMPORARY ARTIST THAT DEFIES EASY CATEGORY LABELS IS THE SUBJECT OF A RETROSPECTIVE AT THE COLLECTION DE L’ART BRUT IN SWITZERLAND

The Paris-based, French artist Michel Nedjar is one of the best known and notable contemporary creators of art brut; his striking, psychologically intense drawings, paintings, and mixed-media assemblage works, especially his “poupées” (dolls) have earned him a central place in the canon of visionaries in this field.

Nedjar was born in 1947 into a Jewish family of Ashkenazi and Sephardic ancestry. His father emigrated from Algeria to France, and his mother moved from Poland to Paris in the early 1920s to escape her homeland’s pogroms.

In past interviews, the artist has said that, as a young teenager, he became aware of his family’s history during World War II when he saw the 1956 documentary film Nuit et Brouillard (Night and Fog). Directed by Alain Resnais and written by Jean Cayrol, the film featured the abandoned grounds of the Nazis’ Auschwitz and Majdanek concentration camps in formerly German-occupied Poland and recounted the horrors of Hitler’s campaign to eliminate Jews, homosexuals, and other targets of his destructive political movement’s persecution.

Many years later, in the late 1960s, Nedjar discovered the colorful, deeply personal, fantasy-rich works of the Swiss art brut creator Aloïse Corbaz (1886-1964). Both the impact of Nuit et Brouillard and his encounter with the paintings of Corbaz prompted Nedjar to begin making art himself. In the 1970s, he traveled throughout Europe and also to North Africa, Asia, Mexico, and Guatemala, observing practices and absorbing ideas related to folk art and folk magic traditions.

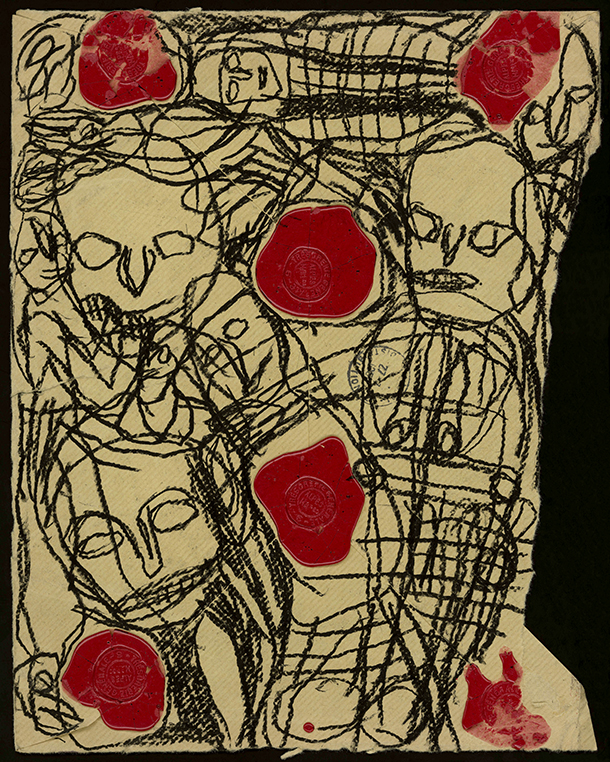

He was especially interested in dolls used for magical-spiritual purposes and, after returning to Paris in 1976 and while affected by depression, he started producing his own strange-looking dolls made with found scraps of fabric dipped in dirt, colored dyes, or even animal blood. Alluding to death and physical suffering, Nedjar’s mysterious dolls honored the memory of the victims of the Nazis’ program of terror.

Over the many years of his artistic career, Nedjar has created drawings, paintings, and a wide range of mixed-media works, often employing fabric and needlework. Through October 29, the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, the leading museum in the world specializing in the creations of visionary, self-taught artists, is presenting Michel Nedjar, a retrospective exhibition showcasing the French auteur’s work across several genres and in various media.

It is laid out in a mostly chronological manner, grouping together various series of Nedjar’s works and presenting as many of the artist’s mixed-media dolls as it does his drawings.

The exhibition has been organized by Anic Zanzi, one of the museum’s long-serving staff curators, who recently shared with brutjournal her observations about Nedjar’s art and the current exhibition’s themes.

brutjournal: What was the inspiration behind this new exhibition of Nedjar’s work? Were you inspired to assemble a retrospective after seeing, for example, the artist’s more recent, more colorful mixed-media works?

Curator Aniz Zanzi: At first, I wanted to evaluate the Nedjar holdings in the Collection de l’Art Brut’s permanent collection. In 2015, Michel Nedjar donated 110 of his works to the museum, and it seemed important to me to exhibit a portion of them. I proposed to Sarah Lombardi, the museum’s director, that we devote an exhibition to Nedjar in order to showcase the scope and the diversity of his artistic production over a period of almost 50 years.

Although we have presented Nedjar’s works for a long time in the permanent collection and in various temporary, group, or thematic exhibitions, the Collection de l’Art Brut had never before presented a monographic Michel Nedjar exhibition. In organizing the current show, we worked directly with the artist.

He wanted most of the series of works he has produced to be represented, and with this in mind, this year, he donated an additional 39 works to the museum. The subject matter of these other pieces are not necessarily different [from those of the other works we already had], but their formats are more varied and their colors are more vivid.

brutjournal: The category known as “art brut” is characterized by a great diversity of creators and remarkable works of art, but as you see it, what especially distinguishes Nedjar’s overall oeuvre and his artistic vision?

Curator Aniz Zanzi: One can pose the question to Nedjar: Is he an art brut creator? It’s a valid question.

If one refers strictly to the criteria [defining the phenomenon of art brut] that were set out by Jean Dubuffet, Nedjar’s work responds to some of them, such as, for example, the fact that the artist is self-taught and that he uses materials that haven’t been used before or that have been repurposed. Nevertheless, he is neither withdrawn from the cultural mainstream nor indifferent to the regard of others.

Today, the notion of art brut is too strict to define his work, which has long been exhibited in museum-quality institutions around the world. However, it’s from the angle of art brut that it all began for him. Nedjar remembers a decisive moment when, at the age of 22, in 1969, in an art-history book his younger sister Sylviane had given him as a prize when he finished his studies, he discovered a drawing by Aloïse Corbaz, which astonished him.

He recalls how that work moved him. He told himself, “If that is recognized as art, then everything is open for me. Everything is possible. Aloïse gave me permission to make ‘something.’” He affirms that his aesthetic vision completely changed thanks to [his encounter with] that picture.

As a creator, the links that Nedjar has maintained and still maintains with art brut but also as a collector are multiple. With regard to those that connect him with the Collection de l’Art Brut, it’s worth mentioning that, already in 1981, Jean Dubuffet first acquired some of Nedjar’s dolls, and that Michel is one of the rare artists whose works Dubuffet collected who is still alive today. The CAB opened to the public in 1976, with Dubuffet’s donation to the city of Lausanne of all of the art brut works he had collected serving as the initial core of the new museum’s holdings.

Editor’s note: The city of Lausanne owns, funds, and oversees the administration of the Collection de l’Art Brut. It is one of three museums that are owned and operated by the city. Zanzi pointed out that the museum opened in 1976 with the Swiss art historian Michel Thévoz, who knew Dubuffet well, serving as its founding director. In 1982, Thévoz himself traveled to Paris to visit Nedjar at his studio. At that time, he acquired several more of the artist’s drawings and dolls for the Collection de l’Art Brut. Nedjar’s works have regularly been displayed at the museum in ongoing presentations of its permanent collection.

In the catalogue that accompanies the Collection de l’Art Brut’s current Nedjar exhibition, Zanzi writes:

“It opens with an immersion in the universe of Michel Nedjar with a presentation of an important number of his ‘Chairdâmes’ [early works from the late 1970s and early 1980s —mysterious figures made with fabric, string, and dried dirt] next to some of his older dolls. The course of the exhibition is largely chronological, offering as many dolls as it does drawings.”

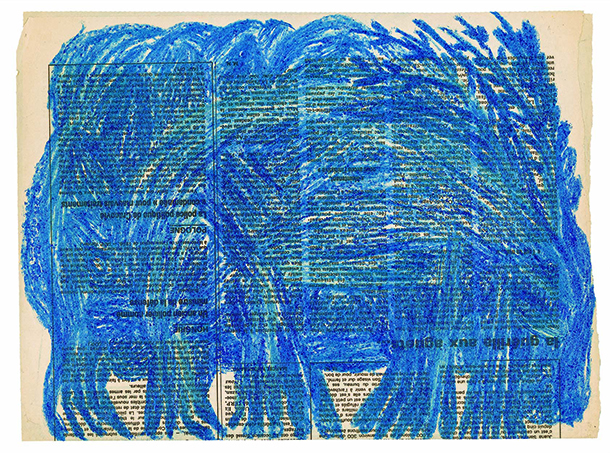

She notes that Nedjar has always made drawings even as he has created his dolls, but that the making of his strange, mixed-media dolls may be seen as the center of all of his artistic activity. Pieces of old fabric, each of which, Zanzi points out, is known as a “schmatta” in Yiddish, are his favorite materials. He has produced groups of drawings under such series titles as “Animo,” “Masks,” “Crowds,” “Icons,” “Presences,” “Writings,” “Summoned Faces,” and “Kalata.”

“With the passage of time,” Zanzi writes, “one perceives a progressive evolution in the work of Michel Nedjar to which the exhibition bears witness. Its themes are not necessarily different, but the formats [he has employed] are more diversified, and his colors have become more present and vivid.”