IT “DEMATERIALIZED” TRADITIONAL ART OBJECTS AND CHANGED PERCEPTIONS OF ART’S VERY NATURE AND PURPOSES

by Edward M. Gómez

photographs by Bill Westmoreland

An old joke from the so-called Golden Age of Advertising in the United States, which, for cultural historians, flourished from the 1960s through the late 1980s, goes like this:

A young member of a big ad agency’s creative team goes in to see his boss. “Yeah kid, what’s up? Whatcha got for me?” his wannabe Rat Packer of a manager says by way of a greeting.

Hoping to score some points for originality and imagination, the young man replies that he has an idea about some changes to make in an advertising campaign his department has been developing.

“Okay, kid, let’s hear it,” his boss retorts, lighting up another Lucky as the ambitious cub puts forth his proposal, which turns out to be very attractive.

It’s so good, in fact, that his favorably impressed boss, brainstorming out loud about how it could be presented at the next creative-team meeting, advises, “That’s a great idea, kiddo. Now let’s huddle, polish it up — and figure out how to talk it up into a concept!”

Ideas, notions, concepts — human beings generate and process so many of these basic units of thought so rapidly sometimes, and in such non-stop profusion, that one can only wonder if or when the brain ever becomes overwhelmed and exhausted. The brain is a physical organ, of course, the body’s formidable mission-control center; by contrast, what we call “the mind” refers to that intangible complex of rational, emotional, perceptual, cognitive, and willful capacities and functions that inform and are informed by human consciousness.

All works of art, even the most abstract creations, are in some way (or ways) expressions of the motivating ideas from which they spring forth, and the realization of such expressions are usually fueled by some kind of intention or will. An artist decides to make a portrait of her friend and then chooses which materials and techniques to employ to realize the task and give her idea or ideas — about portrait-making, in general, and about an image of her subject, in particular — tangible, expressive, communicative form.

Throughout most of art’s long history in cultures and societies around the world, giving perceptible, material form to artistic ideas usually has meant creating some kind of object or evidence, from charcoal-stick drawings on prehistoric cave walls to Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, or from simple clay vessels to high-tech skyscrapers in Dubai.

Something happened in the 1960s around the same time the three-martini-lunch crowd was devising ever more clever-sounding sales pitches for the postwar boom’s mass-produced schlock from big corporate brands, and legions of newly minted counterculturalists were rattling their love beads. Like other sectors of the economy, the market for modern art was growing; pop art superstars like Andy Warhol had called attention to the role of artists in contemporary society — and to the fortunes that could be made in the art business.

It was against this backdrop that a phenomenon that was initially known as “idea art” emerged, challenging conventional art-making, art-dealing, and art-collecting’s preoccupation with works of art as physical objects — take that, old-fashioned connoisseurship! — and proposing that ideas themselves or the imagining of certain kinds of newfangled artworks, some of which would be impossible to produce in the physical world, could be legitimate art forms in their own right.

How could or would art dealers be able to sell works of art that could not be seen — that were not physical objects, like paintings or sculptures, and could not be handled by or displayed in galleries? What was a traditional art seller or buyer-collector to make of Robert Smithson’s vast “earth works,” whose subject matter, substance, and settings were, in specific locations, the artist-manipulated shape of the land itself?

Looking back at a key part of conceptual art’s history, one finds such artists as Yoko Ono, Dick Higgins, Nam June Paik, Shigeko Kubota, Ben Vautier, Robert Watts, George Brecht, Ben Patterson, and numerous others taking part, in the 1960s and 1970s, in the activities of Fluxus, an international community of art-makers who were generally more concerned with the creative process than with its results.

Many of their works made use of “scores” (borrowing the term referring to written music), or brief texts instructing readers or audience members to take certain actions or to imagine certain conditions, the mere contemplation of which constituted the “production” of their prescribed, immaterial artworks.

In “Painting to Be Constructed In Your Head” (dated “1962 spring”), for example, Ono proposed:

Go on transforming a square canvas

in your head until it becomes a

circle. Pick out any shape in the

process and pin up or place on the

canvas an object, a smell, a sound

or a color that came to your mind

in association with the shape.

[From Yoko Ono, Grapefruit (Tokyo: Wunternaum Press, 1964)]

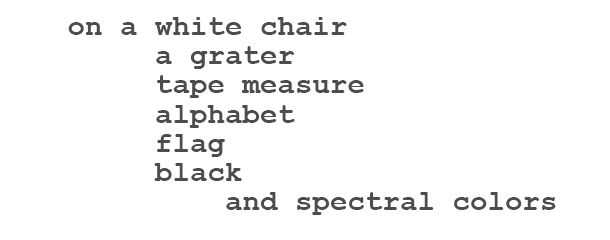

In “Chair Event” (from “Water Yam, 1963), Brecht instructed:

Fluxus participant Henry Flynt referred to his performance pieces as “concept art,” thereby coining a new term. In his book Art after Philosophy (1969), a kind of early manifesto for the emerging new genre, the American artist Joseph Kosuth examined conceptual art’s essential questioning of the nature of art.

Lawrence Weiner, Edward Ruscha, Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, and other artists explored the functions and character of language, or of physical space, or of human perception in projects with which various kinds of texts or photographs were sometimes employed, in a very objective-feeling, scientific manner, to illustrate certain intellectual-aesthetic propositions or to document an artist’s execution of his or her own art-executing instructions.

Back in the early 20th century, the French artist Marcel Duchamp got the conceptual-art ball rolling when he presented industrially manufactured objects — a porcelain urinal, a metal bottle-drying rack — as works of art, simply through the act of appropriating and then “recontextualizing” them by displaying them as artistic creations. But later conceptualists beat Duchamp at his own convention-busting game, as the work of many of the Fluxus artists would demonstrate.

In Six Years: The dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972 (New York: Praeger, 1973), an examination of the new mode of thinking about and “making” art, the American art historian Lucy R. Lippard examined the early, formative period of its evolution, presenting the content of her big book like a data-filled conceptual-art project in its own right.

In this now-classic volume’s introduction, Lippard wrote:

“The era of Conceptual art — which was also the era of the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Liberation Movement, and the counter-culture — was a real free-for-all, and the democratic implications of that phrase are fully appropriate, if never realized. ‘Imagine,’ John Lennon exhorted us. And the power of imagination was at the core of even the stodgiest attempts to escape from ‘cultural confinement,’ as Robert Smithson put it, from the sancrosanct ivory walls and heroic, patriarchal mythologies with which the 1960s opened.”

Fast-forward to today’s contemporary-art scene and art schools just about everywhere. The influence of conceptual art’s aesthetic outlook and ethos can be felt throughout the visual arts and sometimes in other creative fields, too — wherever or whenever a fundamental idea appears to be the motivating factor for and also, often, the subject of a proposed or actually realized, instruction-based or propositional work of art.

Audience participation? Check. No one, definitive iteration of a particular artwork, because it can be recreated repeatedly and endlessly whenever or wherever a viewer or audience member might choose to carry out its instructional guidelines? Check. These are just some of the now-common features of conceptual art that have become ubiquitous in art today.

This month’s issue of brutjournal checks in with a number of contemporary artists who regard themselves as conceptualists or whose work is strongly influenced and shaped by the principles and attitudes of conceptual art.

What’s the big idea?

Dive into this month’s special package of feature articles to find out.