COLLAGE IN THREE DIMENSIONS: AN ARTIST RESCUES FROM THE TRASH A RICH HARVEST OF ART-MAKING MATERIALS

by Edward M. Gómez

When it comes to items made of plastic, Aurora Robson never met a thrown-away bottle, bottle cap, packing tie, industrial part, or interesting-looking packaging component she hasn’t liked — or for which she has not been able to find some worthy use as raw material for her highly original, assemblage-sculpture art.

Robson was born in Toronto in 1972 and moved to New York City when she was 18 years old. There, she studied metal welding, became a certified welder, and began making metal sculptures. Although, earlier, she had not finished high school, she passed the entrance exams for admission to Columbia University, where she earned an undergraduate degree in art history and visual art, graduating with honors. She studied with the artist Jon Kessler, who was known for his mixed-media, kinetic works combining analog and digital components. Kessler’s art often critiqued technology itself.

Robson once noted, “Kessler taught me that art about art was boring.” More recently, she observed, “I’m interested in the idea of learning through serious and playful inquiry as opposed to tortuous drudgery or other ways of learning. I’m interested in art as serious play and as a form of cultural service.”

As a young artist exploring new materials and art-making techniques, Robson became deeply concerned about pollution, consumer-generated waste, and the damage human beings had caused and were continuing to inflict upon the natural environment.

Today, Robson resides with her family in the Hudson Valley region, just north of New York City. As she often puts it, the motivating principle behind her art — it’s a kind of personal and aesthetic ethos at the same time — is that of “rescuing plastic from the waste stream.” Her process and her goal: to take would-be trash that could take a long time to biodegrade and use it as the raw material for making art.

With this in mind, over the years she has developed inventive techniques for handling repurposed plastic. They include an array of methods for cutting different kinds of plastic with assorted tools and coloring her handiwork with non-toxic, environmentally friendly paints, as well as ingenious ways of joining together the component parts of her constructions. (For some time, tiny metal rivets to hold such elements together were the only non-sustainable items in her art-making kit; in recent years, however, she has found tools and developed techniques for using heat to weld plastic parts together without having to use rivets. She has also been sewing together pieces of more flexible plastics.)

If Robson’s sculptural creations may be seen and appreciated as collage works in three dimensions, it’s worth noting that she has long been a maker of two-dimensional collages on paper, too, for which she has routinely cut up and used colorful, printed pieces of unsolicited junk mail.

Recently, we caught up with Robson and asked her about the ideas that have shaped her work. In the context of this issue of brutjournal, with its examination of an array of collage-art expressions, she represents a kind of artist who takes a collage-minded approach to every genre she explores.

About how her creations in different media and genres relate to each other technically or thematically, Robson explained that, in producing her art, she tries to “subjugate negative trajectories” that might emerge as the result of the “troubling aspects of life that I observe and that are shared.” (In fact, she once explained, all of her art evolved as a cathartic response to nightmares and other unpleasant events or circumstances that she had experienced in the past.)

She said, “I’m intrigued by what most people try to ignore or think of as a nuisance or as too big of a problem to address or as simply too mundane. Materials like junk mail and plastic pollution fit into those categories, for example. But from my perspective, they’re also dynamic and in constant flux, which makes them ideal for art applications, because these are lifelike qualities with which many artists strive to imbue their work. Working in a collage-like manner means half the battle of giving your work a pulse is already won, just by virtue of using this constantly moving and morphing material and method.”

About the nature of collage, Robson observed that, as a genre and an art-making technique, there is something about it that is rooted in reality and “provides a more generous, expansive entrée into an art object than more traditional art forms, such as painting, drawing, or sculpture. It’s largely tactile and more direct in a way that no other way of creating art can be. The responsibility of initiating, of where or how to start making a new piece, which for some people can feel very difficult, seems to be removed from the whole process. ”

“Collage also allows me to explore ways to encourage other creative people and artists to engage in more intentional creative stewardship,” Robson added. She said, “It allows me to suggest that artists engage more in collectively softening the edges between nature and culture. I love art of all kinds but I’m currently quite focused on art that has integrity, meaning, and relevance to the entirety of our species — art that’s a unifying agent, that is, and not divisive.”

More precisely, given the nature of her materials, the artist noted: “I also feel that, through this type of work, I’m able to express that I refuse to accept the notion of refuse, that I refuse to accept the notion of boredom, and that I refuse to take things — or life — for granted.” The message of her art: that nothing is — or should be — wasted or even used or consumed in a wasteful manner.

She said, “I think of my collage work as leaning into both discomfort and joy simultaneously and I wonder how this conscious action [of making art this way] might benefit us as a species, if at all. We’re all confronted with and complicit in creating excess and debris, largely due to a lack of producer responsibility in the constant burn of capitalism. I try to embrace neglected or downtrodden materials, many of which, like plastic, are by-products of the fossil-fuels industries, materials whose production enforces the absurd velocity trap we’ve put ourselves in as a species.”

The ways and means of this system of production, consumption, and waste-making, Robson says, with a sigh, “is just too damned cheap and convenient.”

Resources

The artist Aurora Robson’s website can be found here.

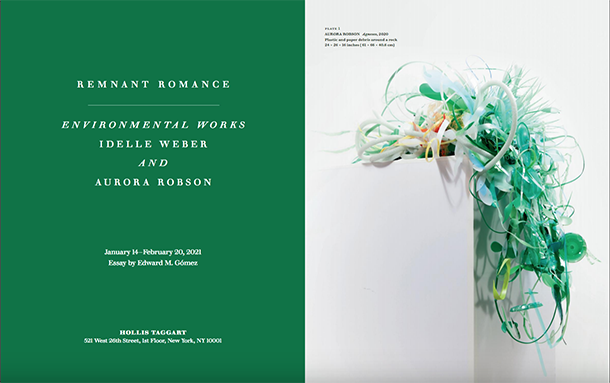

Robson’s work was presented in Remnant Romance: Environmental Works: Idelle Weber and Aurora Robson, a two-artist exhibition at Tollis Haggart, a gallery in New York, in early 2021. Find out about that exhibition here.

Edward M. Gómez’s essay about Aurora Robson’s work and that of the late American artist Idelle Weber (1932-2020) was published in the catalog that accompanied the exhibition Remnant Romance: Environmental Works: Idelle Weber and Aurora Robson. The catalog can be viewed in its entirety here.

Robson’s Instagram account: @aurorarobson