Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts

a film by Jeffrey Wolf, 2021

Distributed by Kino Lorber

Now streaming on www.kinomarquee.com

Available for purchase on DVD here.

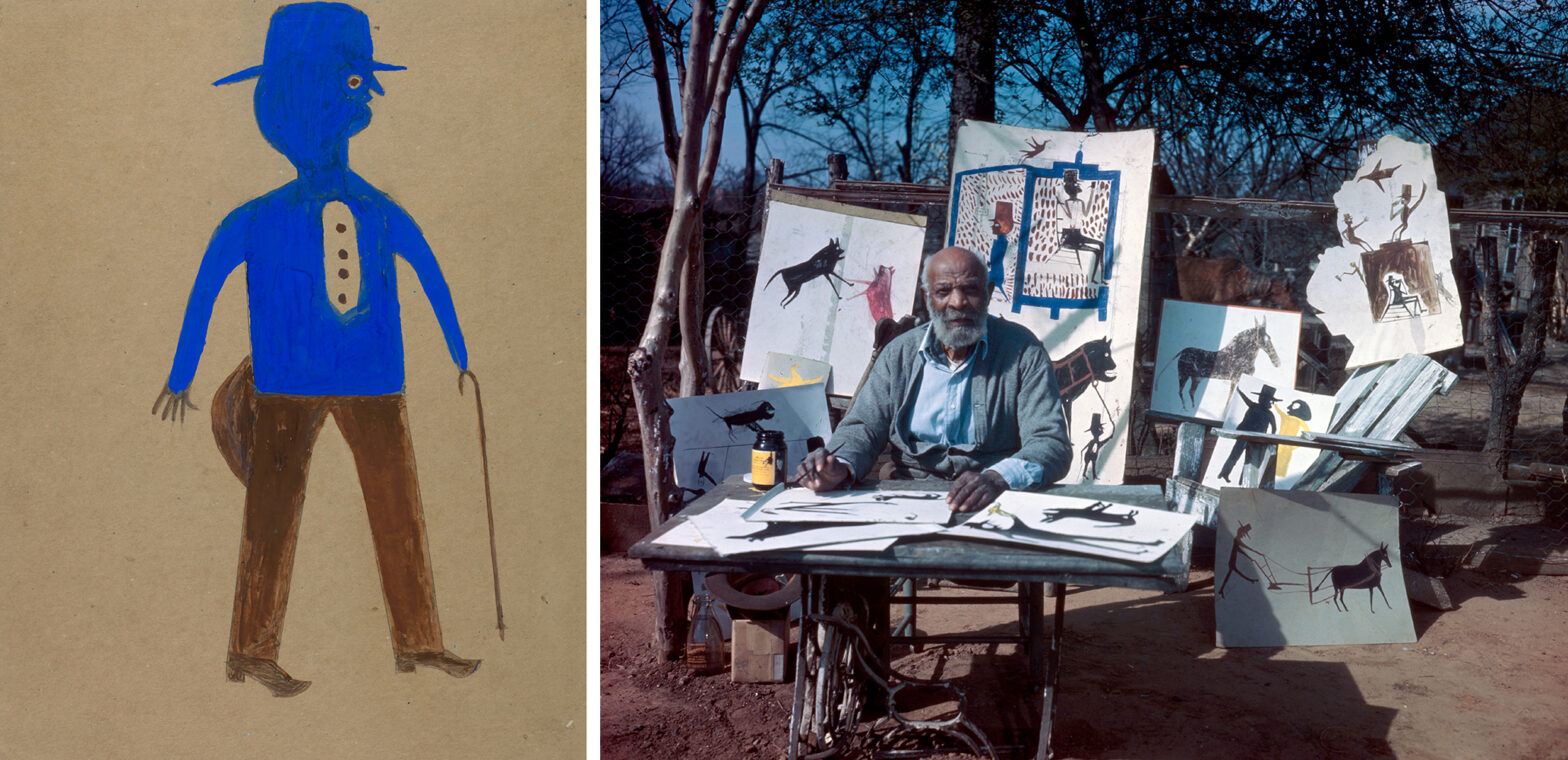

Jeffrey Wolf’s new documentary, Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts, traces the life of its subject, an iconic, African American self-taught artist, through his artworks, archival film footage, and, for this movie genre, unconventional storytelling techniques.

Recently, brutjournal U.S.A. West Coast Bureau Chief Sarah Fensom spoke with Wolf, a veteran Hollywood film editor and passionate collector of self-taught artists’ works, about this new production and the piece-by-piece, quiltmaking-like process by which he created it.

Sarah Fensom reports:

Some 12 years ago, when the filmmaker Jeffrey Wolf undertook the project that would become Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts, he did not have much to go on — no good archival material about Traylor, his family, or the areas around Montgomery, Alabama, where the artist had lived and worked. In fact, even after several years of research, Wolf was able to unearth fewer than ten photos of his subject. He found no audio material that might have captured Traylor’s voice, and he learned that a shack the artist had once occupied had been demolished just a month before he went to visit it.

Today, over 70 years after Traylor’s death, in 1949, the definitive record of his experiences in the world remains the body of energetic and deeply symbolic paintings and drawings he created; in recent decades, they have entered major art collections and commanded large prices at auction.

In a recent FaceTime chat, Wolf said, “It’s hard to weave a history of somebody. The records of people who were indigenous or Black or poor weren’t very well kept during [Traylor’s] time, so you have to dig even deeper to find them.”

The period to which Wolf referred was that of the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries, a period that lines up almost exactly with Traylor’s lifespan (circa 1853-1949). Place is also significant with regard to the kind of record-keeping — or lack thereof — Wolf cited, for Traylor was born into slavery in rural Lowndes County, Alabama, the very belly of the old, feudal American South. He remained there, working as a sharecropper during the Reconstruction period following the Civil War, which was marked by racist Jim Crow laws; in 1909, he moved to nearby Montgomery County to continue farming. Traylor was married twice and fathered nearly 20 children with his wives and other women, but records of the names and lifespans of his family members are largely incomplete.

Wolf relied on legal documents and generic archival imagery to illustrate the sections of his film describing the time Traylor spent in Lowndes and Montgomery Counties — with surprisingly vivid and poignant effects. Wolf recalled, “When [Traylor] family members saw the film at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, in Washington, D.C., in 2018, one wrote to me and said, ‘I’ve never seen those family pictures of the Traylors; can you send me those pictures?’, not realizing that many of them were [generic] archival images I had used to recreate the atmosphere of what was happening at the time.”

Traylor relocated to Alabama’s capital, Montgomery, in the late 1920s. There, he first lived in a small shack and, later, in the streets. (At night, he slept on the floor of the city’s Ross-Clayton Funeral Home.) During the daytime, installed in a spot on Monroe Street, in downtown Montgomery, Traylor made his drawings. Between 1939 and 1942, he produced his entire body of work — nearly 1500 pieces in all.

Monroe Street became Wolf’s first research stop when he began working on Chasing Ghosts with his partner, the producer Fred Barron, in 2008. Wolf said, “We started by looking at old censuses and directories to kind of map the geography of the place. Then we went there and saw that everything we had read about had been plowed over to create a parking garage.”

Wolf and Barron located the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church (now the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church), the Court Square Fountain, and several other historic monuments that are central to Montgomery’s history and appear in Traylor’s work. Wolf said, “We saw the fountain for the first time, the clock, and the Alabama State House, and were able, having seen the drawings, to start understanding that the built environment was something Traylor drew upon.”

Wolf and Barron put together PowerPoint presentations about different aspects of Traylor’s life and showed them to audiences at art fairs attracting admirers of outsider art. At one fair, Wolf reconnected with Leslie Umberger, an art historian and curator of folk art and so-called self-taught art whom he knew; she had recently left the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, to become a curator in her specialized fields at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Umberger, who appears as a commentator on Traylor’s work in Chasing Ghosts, told Wolf she wanted to organize a Traylor exhibition and suggested that they could share their research. (Umberger’s project became Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor, which opened at her museum in 2018.)

“So we did work in parallel, and much of our research overlapped,” Wolf explained. He found color-film footage of Montgomery that had been shot in 1941, which he shared with Umberger, along with local, scenic photographs that that had been taken in 1890 by Mary Morgan Keipp. Wolf noted, “They were shot in a field in Dallas County, probably pretty close to the very same field Traylor was working in. So those things started to bring the story visually to life.”

Even with such valuable finds, Wolf still needed more material to illustrate Traylor’s life and milieu. To supplement on-camera interviews with such commentators as the New York Times’ senior art critic Roberta Smith, the painter Radcliffe Bailey, and the musician and writer Greg Tate, Wolf utilized a cross-disciplinary approach to place Traylor’s work within a broader tradition and context of African American art and culture.

In the film, readings of Zora Neale Hurston’s writings accompany an examination of Traylor’s drawings of animals, and a 1937 song by Coot Grant and Kid Wilson, a Black, wife-and-husband, vaudeville duo plays while Wolf’s camera surveys Traylor’s confrontational images of women and men. Perhaps most evocatively, the tap dancer Jason Samuels Smith, inspired by Traylor’s spirited figures, performs energetically in several scenes.

Wolf initially planned to intercut shots of Traylor works exuding what he called a “dancing quality” with archival footage of the famed hoofers Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Earl “Snakehips” Tucker. However, when the rights to excerpts from the Warner Brothers and Paramount movies Wolf had in mind turned out to be too expensive, he was struck by the idea of shooting a contemporary tap dancer performing in a theater after seeing Savion Glover performing at a jazz club in New York. (His efforts to hire Glover for his film led him to cast Smith, Glover’s understudy in Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk, the 1990s musical revue).

A theater also serves as a setting for Chasing Ghosts’ loose narration. On a stage, the actors Sharon Washington and Russell G. Jones anecdotally recount aspects of Traylor’s biography and Montgomery’s history. Initially, Wolf wanted them to perform as town gossips, arguing over a fence, but that premise, he decided, would have been “too much” — and probably a bit too cute.

About Traylor’s life story, he said, “Because we don’t know if the ‘facts’ are facts, there’s probably a lot of gray area around them. We used the facts as best we could but we knew we wanted [the film] to be poetic and tell a bigger story than just [that of] the [art], so we tried to find ways of talking about the work that did not just show one picture after the other.” Wolf said he wanted to offer viewers “reference points” for understanding Traylor’s life story and artistic accomplishments.

Wolf, who cut his teeth cutting movies — he has edited such feature films as Billy Madison, Holes, and Bachelorette, among others — became enamored with self-taught artists’ works when he was a college student, following a chance encounter with the Mississippi-born wood carver Elijah Pierce (1892-1984). Wolf developed a close friendship with Pierce and helped the artist document his work. In 1982, Wolf saw Traylor’s work for the first time in a Brooklyn Museum exhibition of folk art made by African American artists. Not long thereafter, he acquired several Traylor works from Luise Ross, a New York dealer who played a leading role in the development of the market for outsider art in the United States. (Today, Ross is retired, and her former Manhattan gallery is closed.)

Even as his professional career progressed, Wolf said, “I kept collecting other things, but I knew I had to unravel the Bill Traylor story.”

First, however, Wolf directed James Castle: Portrait of An Artist, a 2008 documentary about the Idaho-based artist James Castle (1899-1977), who used found materials to create drawings, books, and assemblages depicting everyday objects. Wolf said, “I used Castle to explain what an outsider artist is, which in my mind is somebody who has such a firm vision of something that is unique to him — this unbearable need to create, this lifetime commitment to what he’s doing.”

Ultimately, though, Wolf admits that this description can aptly apply to any artist, whether or not he or she lives and works “outside or inside” so-called mainstream society and culture.

In fact, the filmmaker noted, he is “beginning to believe there’s no such thing as ‘outsider art.’” He suggested that the term “outsider art” may have become more of “a brand” designation than a meaningful label for a category of art. He said, “The only way I can use the word ‘outsider’ is in the sense that [the artwork to which it refers] exists in a world outside the mainstream and the history of 20th-century art, because, for whatever reason, people were afraid of it or they didn’t know how to talk about it or how to accept it.”

With films like Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts, Wolf hopes to change such perceptions. Of his research-and-production team, he said, “We’re trying to create a bridge or gateway to understanding what [Traylor’s] accomplishments were and that he’s truly an American master.”