THE POGUES FRONTMAN CELEBRATES LIFE’S ETERNAL BUZZ

Shane MacGowan: The Eternal Buzz and the Crock of Gold

Andipa Gallery

162 Walton Street

London SW3 2JL

England, United Kingdom

October 12 – November 5, 2022

by Luciano Oltramari

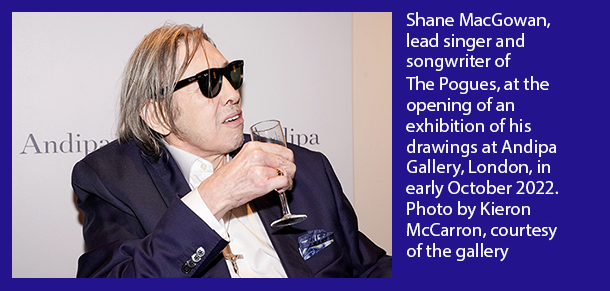

Recently, in London, the musician Shane MacGowan, who was born in England to Irish-immigrant parents and is best known as the lead singer and songwriter of the band The Pogues, revealed another big side of his creativity — his work as a visual artist. In a solo exhibition presented at Andipa Gallery, a venue known for its presentations of modern and contemporary art, MacGowan showed a selection of his drawings made with pencil, ink, watercolor, and other media on paper.

The “eternal buzz and the crock of gold” to which the exhibition’s title referred — it’s also the name of a book filled with MacGowan’s art that was published earlier this year — alludes to the good fortune or the valuable, elusive, mythical treasure anyone might be lucky enough to find. For MacGowan, it seems, and as his art suggests, the prospect of landing upon a crock of gold generates some kind of hopeful or optimistic energy that may be seen, in its own way, as an “eternal buzz” — in this performer and artist’s case, as the “buzz” of a life that has been filled with excitement, music, and art, but also with long spells of drug addiction, poor mental health, and alcoholism.

In an interview with the British magazine the Spectator published earlier this year, MacGowan observed, “Sometimes people visit, or we go out to dinner, or sometimes I end up in hospital. If I don’t end up in hospital, I thank Jesus and His Holy Mother and all the saints and angels.”

Nowadays, he is likely to be showing gratitude to the saints and angels in whom he and his wife, Victoria Mary Clarke, have deep faith; that’s because, earlier this month, MacGowan was admitted to a hospital, but he was discharged on December 14, in time to be able to celebrate his birthday, which falls on Christmas Day.

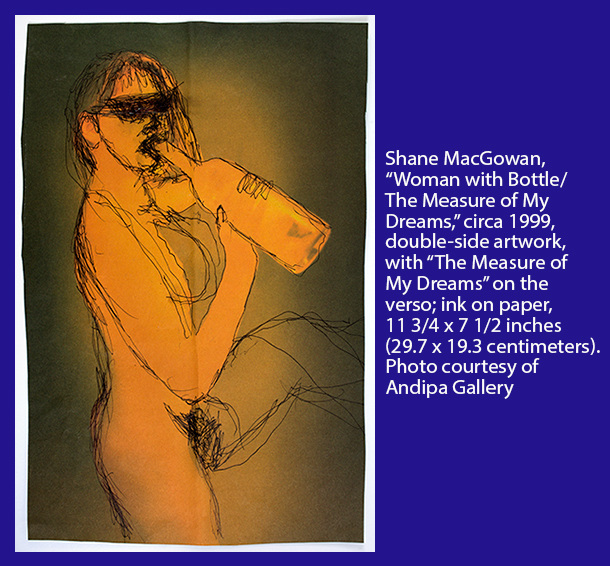

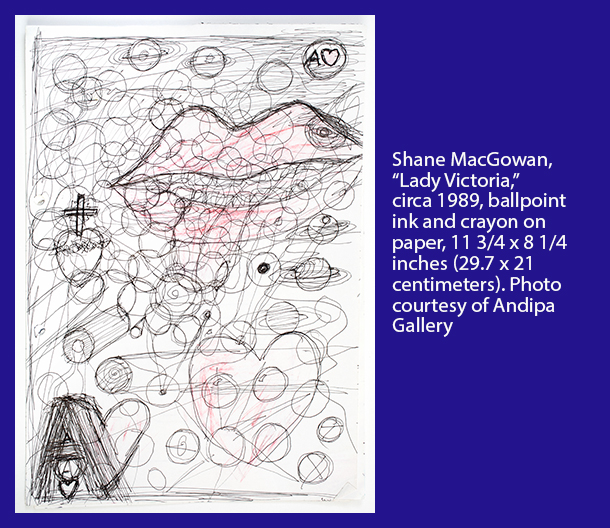

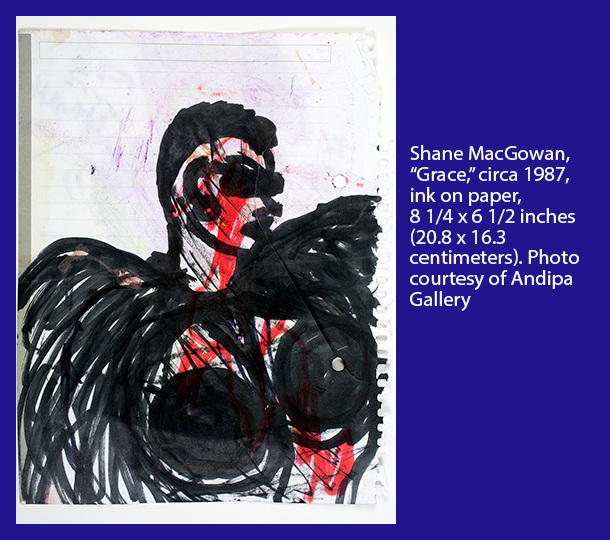

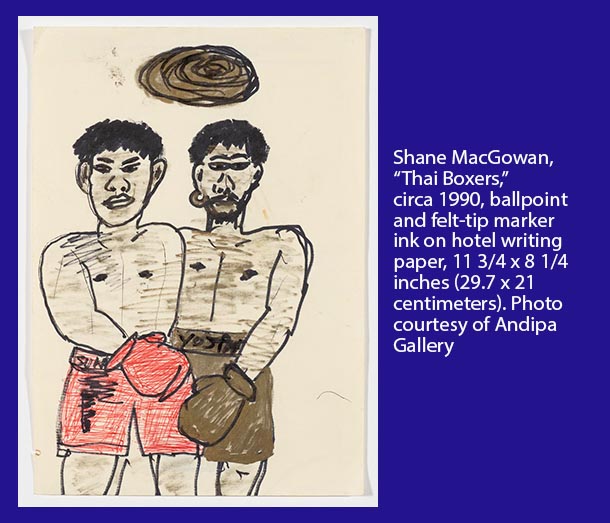

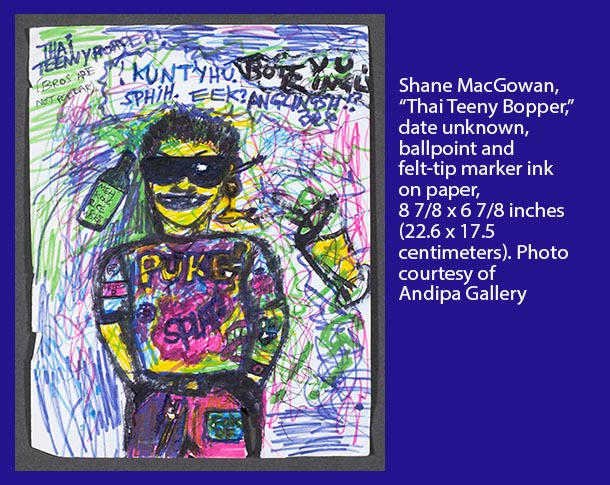

Known as a lyrical artist and songwriter, MacGowan uses ballpoint-pen ink and other media on paper to produce visual poetry in the form of drawings and sketches. His pictures reflect and lay bare his mental and emotional states, dreams, thoughts, and visions. In an interview with Liza Lentini published in Spin’s April 2022 issue, MacGowan said, “I don’t think that anything that you draw or paint is not a self-portrait. Everything you create is coming straight out of your subconscious, and it is all your essence […].” Perhaps, in MacGowan’s case, the personal essence he cited refers to a spirit of youthful rebellion and his sense of freedom, which can be felt in his artworks, in each of which some kind of energy seems to be aching to come alive. Each of his drawings hints at some kind of a story.

MacGowan’s exhibition at Andipa was born after Clarke discovered that, for several decades, her mother had been holding onto a stash of MacGowan’s artworks. In Lentini’s Spin article, Clarke explained that, during the making of Julien Temple’s 2020 documentary, The Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan, which examines its subject’s life, from his childhood in a farmhouse in Tipperary, Ireland, through his years with the Pogues and his more recent activities, Temple had wanted to acquire some of MacGowan’s drawings for himself. When Clarke asked her mother if she happened to have any of Shane’s works of art, she received a garbage bag filled with his drawings and song lyrics. It turned out that, 25 years earlier, Clarke had asked her mother to look after that material and had forgotten that it still existed.

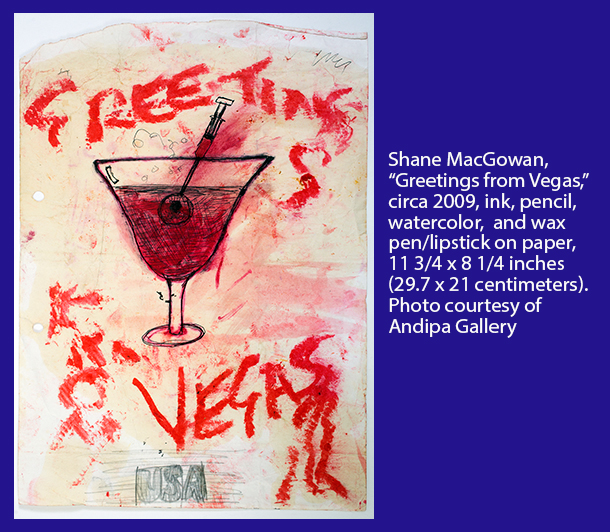

Looking through it, Clarke found that MacGowan had made pictures on airline air-sickness bags, hotel stationery, recording-studio worksheets, shopping lists, and other re-purposed materials. Clarke told Spin, “It was miraculous, like finding a crock of gold! His art brings back lots of very funny and often hideous memories of different stages of our life together […].”

“The Eternal Buzz and The Crock of Gold” is also the title of MacGowan’s first book, featuring his art, which was edited by Paul Trainer and co-published earlier this year by Rain Street and Infinitum Nihil. Issued in a limited edition of 1000 author-signed copies, the 502-page volume also contains reproductions of the musician-artist’s handwritten lyrics and previously unpublished writings. The book includes an essay by the Sunday Times’ chief art critic, Waldemar Januszczak (formerly the head of arts programming at Britain’s Channel 4 television network) and a foreword by the actor Johnny Depp (one of MacGowan’s pals and the founder of Infinitum Nihil), along with other contributors’ offerings.

Many of the artist’s pictures recall moments from his turbulent, fascinating, creative life. In its recent MacGowan exhibition, Andipa, a gallery in central London’s upscale Knightsbrdge district that has been in business since the late 1960s and, in recent years, has become the go-to spot for works by the street artist Bansky, presented 20 of the Pogues frontman’s small-scale drawings, most of which dated from the 1980s.

About these works, MacGowan noted in his Spin interview, “Some of the stuff I don’t remember doing[;] some of it I do, but it was pouring out of me all over the place all the time, a lot of the time when I was very stoned!” Sexuality, religion, drugs, Irish symbols — these are some of the subjects of the artist’s drawings; they’re also some of the abiding themes of his life.

The Pogues composed much of Hell’s Ditch (1990), their fifth studio album, during a stay in Pattaya, Thailand, where, among other songs that appeared on the record, MacGowan wrote “Summer in Siam” and “Sayonara.” When he traveled with Clarke in Thailand in the 1980s, MacGowan had been attracted by that country’s vibrant atmosphere, the beauty of its Buddhist statues — and its abundance of easily available drugs and booze, from LSD and other hallucinogens to opium, China White (a synthetic heroin), Valium, Mekong whiskey, and Singha beer (a Thai pale lager).

Back then, MacGowan hung out on the beach, where he shared joints with dodgy characters after bar-hopping late at night and watching Thai boxing. He became obsessed with “Thai Beat,” a local style of pop music, which he listened to non-stop, at high volume. He became interested in stories about American soldiers who had come from Vietnam to Thailand (and were in Thailand when MacGowan was there) and about the locals who worked in the tourist-oriented bars. The raw beauty and the chaos of MacGowan’s experiences in Thailand fueled his creativity.

Unlike many rock musicians who studied at or graduated from art schools, MacGowan has no formal, academic training as a visual artist; he started to paint and draw when he was a young boy and later did his own research about art history and sought out works of modern art that had seized his imagination — paintings by such artists as Wassily Kandinsky, Salvador Dalí, Paul Cezanne, and various Irish impressionists, among others. About his own drawings, MacGowan told the Spectator, “I came, I saw, and I scribbled,”

Whatever the moods or methods out of which his drawings emerge, behind their bursts of purple, green, blue, pink, yellow, reds, and other colors, in the depths of MacGowan’s images, some viewers may detect currents of happiness and sorrow. The artist’s expressions of such emotions can feel daunting, disturbing, pleasant, violent, or peaceful.

Whether made with simple ballpoint-pen ink, watercolor, acrylic paint, or a more unexpected material, like Clarke’s lipstick, MacGowan’s art offers a reminder that no one and nothing is eternal, but instead that life or the life force can — and perhaps should — be regarded or appreciated as some kind of energy — as some kind of precious and eternal “buzz.”

Luciano Oltramari is a Brazilian-born, London-based musician, translator, and researcher with a background in advertising.