ROLAND HAGENBERG PAYS HOMAGE TO AN ARTIST WHO DIED YOUNG IN AN EXHIBITION THAT RECALLS HIS TRAGIC-HEROIC LIFE STORY

by Edward M. Gómez

Throughout the history of art, some artists have been influenced by the ideas and creations of other art-makers as they have developed their own thoughts about and techniques for producing their own works.

In many a textbook, art historians still write, for example, about how certain artists “worked their way through” or “assimilated” the work and ideas of particular Renaissance painters or such stylistic approaches to art as Cubism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, or Pop Art on the way to or before developing their own distinctive art-making styles and methods.

Similarly, often in art history, artists will pay homage to the creative forbears or the contemporary peers whose achievements they admire and by which they have been influenced by creating paintings, drawings, or other works either in styles reminiscent of those of such sources or in ways that allude to such source material.

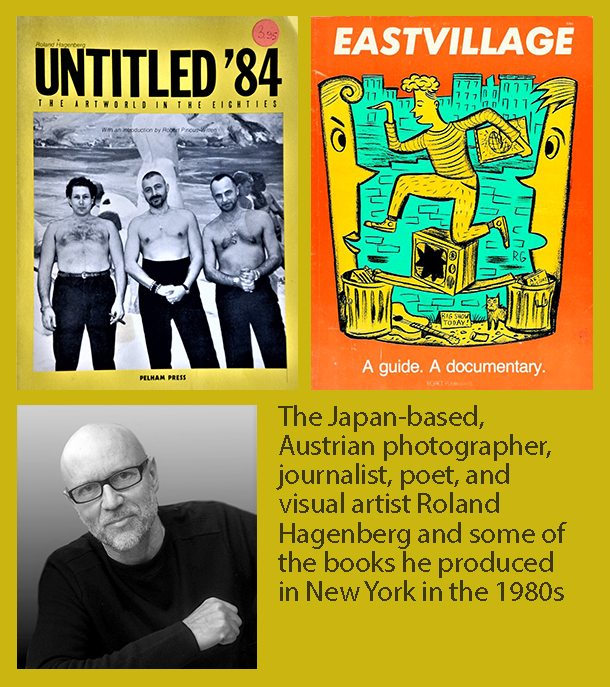

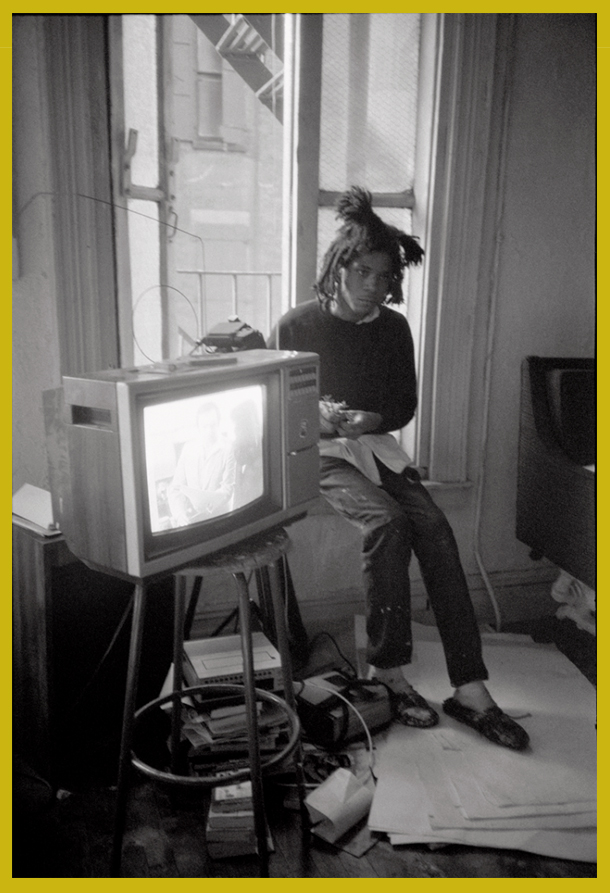

So it is that, earlier this month, in Tokyo, Roland Hagenberg, a photographer, journalist, poet, and visual artist who has lived and worked in Japan for more then three decades, presented a small exhibition that paid homage to the work of an artist whom he knew and whom he photographed when he lived in New York during the 1980s.

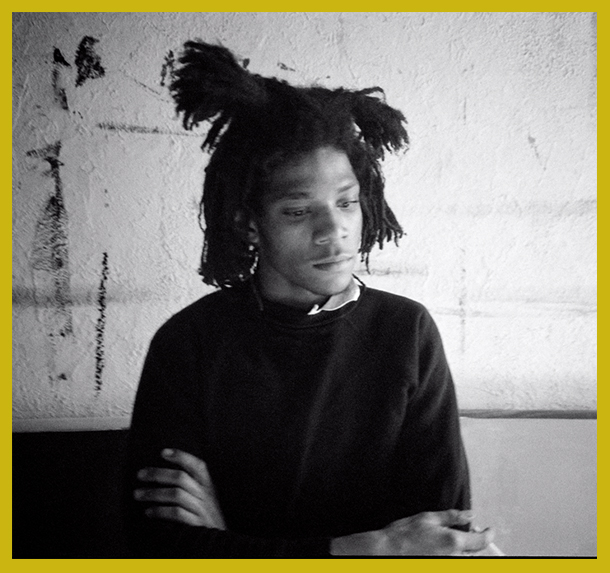

That artist was Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), a painter of Haitian and Puerto Rican ancestry who first became known as a graffiti artist in the 1970s and who, by the early part of the following decade, had become internationally known as a representative of what the art market, which always loves — and, in order to help move merchandise, needs — a label had dubbed “Neo-expressionism.”

The early 1980s was an effervescent time in New York’s overlapping, downtown-Manhattan art, music, fashion, performance, and independent-media scenes. In that pre-Internet, pre-mobile-phone era, storefront galleries, especially in downtown Manhattan’s East Village district, along with nighttime music clubs, became vital meeting places for young artists, some of whom had opened and were operating galleries themselves. Punk music was giving way to New Wave sounds, and a sense of cool, ironic detachment born of the influence of the ideas of postmodernist critical theory, which were circulating throughout the avant-garde, seeped into the looks, styles, and attitudes of productions in many creative fields and genres.

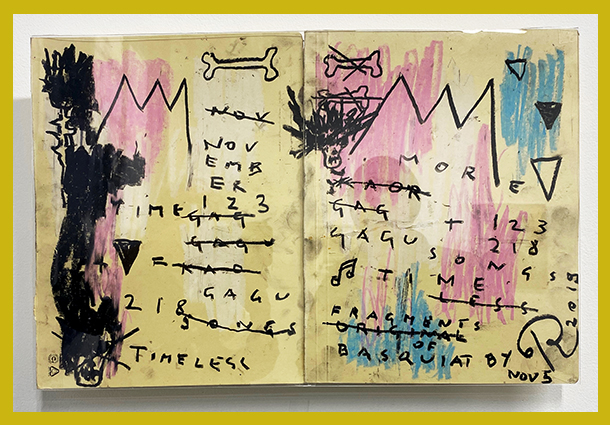

By contrast, with its mix of images and handwritten texts, its emphasis on simple, urgent-feeling draftsmanship, and its thematic references to racism, colonialism, and class struggle, Basquiat’s art exhibited the soulful touch of the artist’s hand. His star rose swiftly in the 1980s; by 1982, the young artist had left Annina Nosei’s gallery in New York, and the Zürich-based art dealer Bruno Bischofberger had become his worldwide representative.

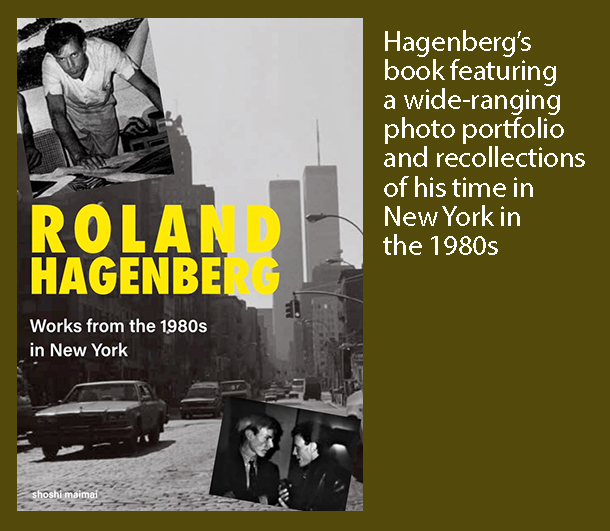

Hagenberg lived and worked in New York from 1983 through 1992. During that period, in addition to his photography work, he collaborated on the production and publication of numerous books that documented various aspects of the era’s downtown-Manhattan creative scene. Among them: the books Untitled ’84: The Art World in the Eighties (New York: Pelham Press, 1984) and East Village ’85 (New York: Egret Publications, 1985), and the magazine Artfinder Magazine, a quarterly guide to the arts in New York, which was issued regularly by Egret Publications from 1984 to 1987.

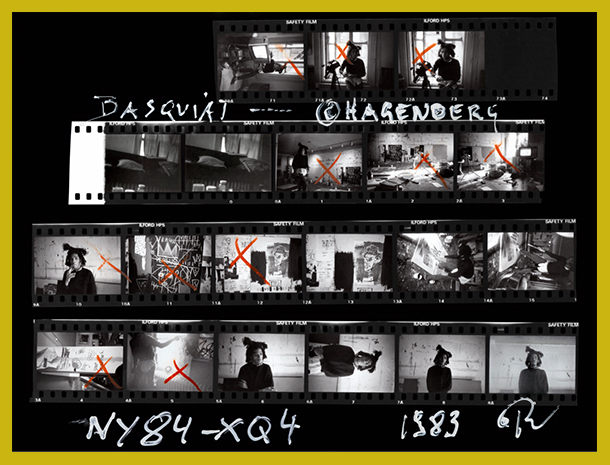

During this time, Hagenberg met Basquiat several times. He visited and photographed the artist’s studio; he also photographed him at work and at rest. In recent years, Hagenberg’s rare photographs of Basquiat have figured prominently in several exhibitions of the American artist’s work and in the catalogues that have accompanied them. Some of these museum presentations have included, among others, Basquiat: Boom for Real, which was seen in 2017 and 2018 at the Barbican in London and the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, Germany; Jean-Michel Basquiat: Made in Japan, which opened at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, in 2018; and Jean-Michel Basquiat: Seeing Loud, which opened in October 2022 at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, in Canada.

Hagenberg’s recent exhibition, Jean-Michel Basquiat: Fiction + Fact, Stations of the Cross, was presented at SO1, a small gallery in Tokyo’s Harajuku district. To set the scene, it featured several of Hagenberg’s photos of Basquiat and the artist’s New York studio as it appeared in the early 1980s. It also included a group of small-format paintings Hagenberg had created in a style reminiscent of Basquiat’s spontaneous-feeling mode of image-making with its simply outlined forms and impulsive patches of color.

Somewhat audaciously, Hagenberg’s pictures illustrated what he proposed, taking a page from Christianity’s story of the so-called passion of Jesus Christ (the sequence of events that took place in the short period before the prophet’s death), as the “passion” of Jean-Michel Basquiat. That is, both respectfully and with a nod to the ways in which, in the years following Basquiat’s death, the art market and the broader, international art establishment have canonized the artist who died of a heroin overdose at the age of 27, Hagenberg proposed a telling of his rise and demise, symbolically, in the context and in the trappings of the familiar Christian “passion” tale.

Traditional Christian imagery portrays this story in what are known as “The Fourteen Stages of the Cross,” or the 14 main events that took place in the short period leading up to Jesus Christ’s death.

Thus, in Hagenberg’s “Passion of Jean-Michel Basquiat,” the third event in Christ’s Passion, in which Jesus, carrying the heavy wooden cross on which he will be crucified by the Romans, falls down, is compared with a decisive event in Basquiat’s early life — an accident that occurred when he was seven years old and was hit and injured by a car while he was playing in the street.

As a result, the young Basquiat was hospitalized and underwent an operation on his spleen. As the arts writer Phoebe Hoban noted in New York magazine in 1988, while Basquiat was recovering from that surgery, his mother visited him in the hospital and gave him a copy of the book Gray’s Anatomy.

In an interview at the gallery in Tokyo, Hagenberg told me, “In many of Basquiat’s paintings, there are bones and references to the human body. Apparently, he was deeply affected by that childhood accident.”

Christianity’s telling of Christ’s Passion, or “The Fourteen Stages of the Cross,” includes such events as Jesus meeting his mother as he makes his way, bearing his heavy cross, to the site where he will die; the weeping of a group of women at the sight of the struggling, suffering holy figure; and the Roman executioner’s nailing of the condemned man to the cross he has delivered to them.

By contrast, in the Basquiat “Stations of the Cross” Hagenberg has imagined, key events in the died-too-young American artist’s “passion” include, among others, the beginning of his public art-making career, with his school friend Al Diaz, as one half of the graffiti-art duo SAMO; his first encounter with the world-famous Pop Art artist Andy Warhol, with whom he would later create collaborative paintings; his death as a result of a drug overdose; and his “resurrection” as an iconic, tragic hero in the “temples” of the international art establishment — its galleries, auction companies, museums, and magazines — whose creations are now worth millions of dollars.

Hagenberg said, “I knew Basquiat and I watched with fascination, as did so many others who knew him or who were aware of his art, as his career quickly advanced. Today, the debate still rages on: Was it the pressure of success that killed him? The pressures and demands of a market that saw him, as much as it did his art, as a kind of commodity? My ‘Stations of the Cross,’ which is both compassionate and ironic, calls attention to how such pressures may have weighed upon this thoughtful, sensitive young artist’s thinking and spirit.”