WITH VERY FEW CLUES OR LEADS TO FOLLOW, AN ENIGMATIC ART-MAKER’S IDENTITY WAS REVEALED

Published on February 10, 2026

In this recollection,brutjournal contributing photographer and artist Steven Hirsch looks back at his recent discovery of Tancred Calhoun’s strange artworks and his efforts to uncover some information about the late, self-taught art-maker’s life.

by Steven Hirsch

NEW YORK — Every Saturday, I try to make it to the flea markets in my neighborhood in downtown Manhattan. This has become a ritual. Over the years, among the treasures I’ve found, some amazing finds really have stood out. Among them: a valuable photographic print by Mike Disfarmer, which I picked up for ten dollars, and an abstract painting from the 1970s ($75.00) that once had been exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art. I’ve learned to look for the untold treasures people let go of without realizing what they have.

[Editor’s note: Mike Disfarmer (1884-1959) was an Indiana-born photographer who became known for his portraits of local people in rural Arkansas from the 1920s through the 1950s. His work was rediscovered in the 1970s and is now greatly admired for its artistic qualities.]

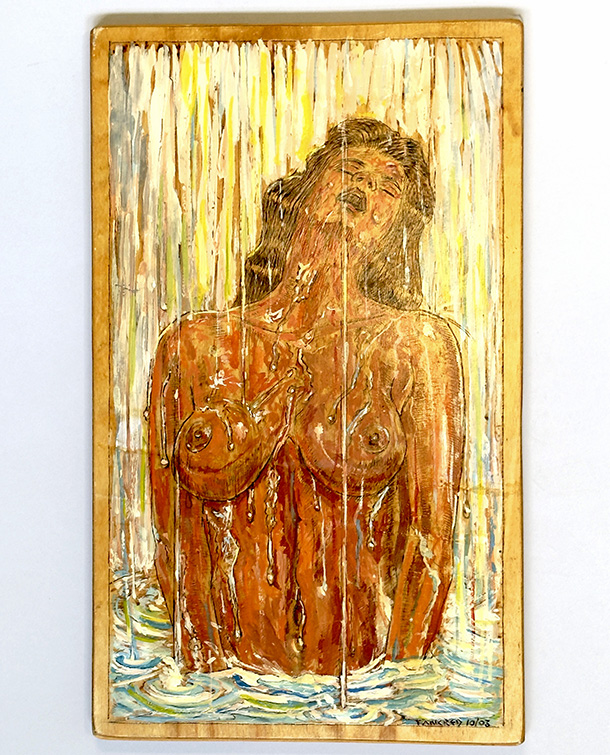

Looking back, maybe all of my rummaging around at flea markets led me to the work of a self-taught artist whose name, I would later learn, was Tancred Calhoun. I found the first few of his “paintings” — actually, they’re images burned into wood surfaces and then painted —tucked away between a pile of discount toiletries and a bin of junk electronics.

These colorful, heavy, handmade objects, which I found sitting next to discarded remote-control devices and old shampoo bottles, looked completely out of place. Immediately, I sensed that I couldn’t leave them there — that I had found a treasure trove of strange images from someone’s powerful, private world. I begged the vendor who was offering them not to sell them to anyone else while I ran to a nearby bank to squeeze enough cash out of an ATM so that I could buy them.

The artworks I had found had been signed with a single name: Tancred. When I asked their seller if he could tell me from whom he had acquired them, he said that he lived in a building just a few blocks away. He told me that the janitor in his building had been tasked with cleaning out an apartment following the death of a certain tenant — that person was, I would later find out, Tancred Calhoun.

Since the janitor knew that the vendor sold odds and ends at a flea market, he gave him the paintings he had come across in Calhoun’s empty apartment just to see if he could make a few dollars.

I went to check out that apartment building for myself. It was Tanya Towers, a high-rise in the East Village housing seniors, military veterans, and people with disabilities, including a large number of deaf and mute residents. There, I met the janitor whom the flea-market vendor had mentioned to me. He confirmed the vendor’s story and told me that he had even more of Calhoun’s paintings stored in the basement. At that point, I still didn’t know the full name of the person who had made the artworks. I asked the janitor for the unknown artist’s full name, but he didn’t know it.

During my visit to Tanya Towers, I went upstairs to the floor where the now-deceased maker of the burned-wood pictures had lived. I started knocking on doors. It was a somewhat surreal experience, for many of the residents who opened their doors were deaf or mute. Only one resident could tell me anything at all; this person remembered an “old man down the hallway” who had been wheelchair-bound. I was stumped. I had the artworks, but the man who had made them had vanished.

The apartment building’s janitor offered me a potentially valuable clue: He said that, even though the man about whom I was seeking information had died five years earlier, his name might still be listed on the building’s directory of residents, downstairs in the lobby. Together, we checked it out, and there it was — a small piece of plastic bearing the full name “Tancred Calhoun.”

Plugging in that name, through an Internet search, I found a brief obituary for someone named Tancred Calhoun; it had been written for a Vietnam Veterans’ blog by Steven Grossman, a licensed social worker who had seen Calhoun for many years in the role of psychotherapist. It took some effort to track Grossman down, but when I finally did, he shared his memories of Calhoun with me in a friendly phone conversation.

He told me that Calhoun had served in the Vietnam War in the early 1970s and had later suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Calhoun took part in a support group for Vietnam War vets that Grossman oversaw at a Veterans Administration hospital in downtown Manhattan.

There, too, Grossman served as Tancred’s therapist for the last 20 years of the U.S. Army vet’s life. Nevertheless, he informed me, he knew very little about Calhoun’s personal story. He didn’t know where Calhoun had come from when he moved to New York or even where he had been born. Grossman was familiar only with the details of Calhoun’s troubled life during its later years.

Tancred Calhoun was born in 1947 and died in 2020. In addition to PTSD, he was affected by schizoaffective disorder [a mental-health condition combining symptoms of schizophrenia and mood disorder symptoms]. Grossman explained that, during the latter part of Calhoun’s life, when he saw him regularly as a patient, the U.S. Army vet’s world was defined by some significant boundaries. For example, in addition to his mental illnesses, he weighed more than 300 pounds and moved with difficulty, using a wheelchair.

In the building in which he lived, a place full of people who carried their own scars, Calhoun spent many days hunched over his art boards, the smell of singed wood and paint filling his apartment while the city hummed outside.

I went to the Veterans Administration hospital where Calhoun also had spent a lot of time. I wanted to see if I could find anyone else, besides Grossman, who might have known him or maybe find a photograph of him, but my efforts were to no avail. I found the room in which Calhoun used to paint, but the hospital’s current staff psychotherapist had only been there a few years and knew nothing about the late artist.

I sat in the lobby for a while, observing veteran-patients coming and going. Many wore their old Army camo. Some got around in wheelchairs. As I watched them, I tried to visualize what it must have been like for Tancred Calhoun to have moved around through the hospital’s halls.

Grossman had mentioned that Calhoun had painted murals somewhere in the building. After roaming the hallways for hours, I finally found them in a second-floor corridor. They were spectacular and offered vivid proof that his creative vision couldn’t be contained in a single room or by a small wooden board.

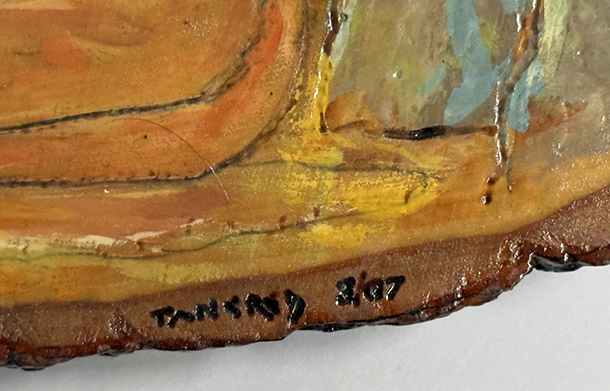

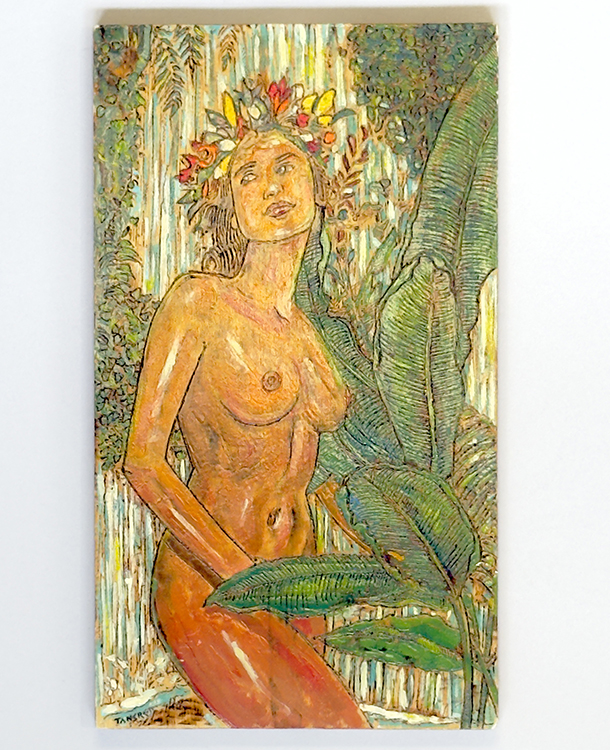

Among the small-format, burned-wood Calhoun works I acquired, some of them are triptychs with hinged panels, while others are individual images made on slabs of wood on which thick, outer rims of bark still cling to their edges. They’re all covered in the scorched, precise lines of Calhoun’s pyrography pen, which he then painted over to create an illusion of tactile depth.

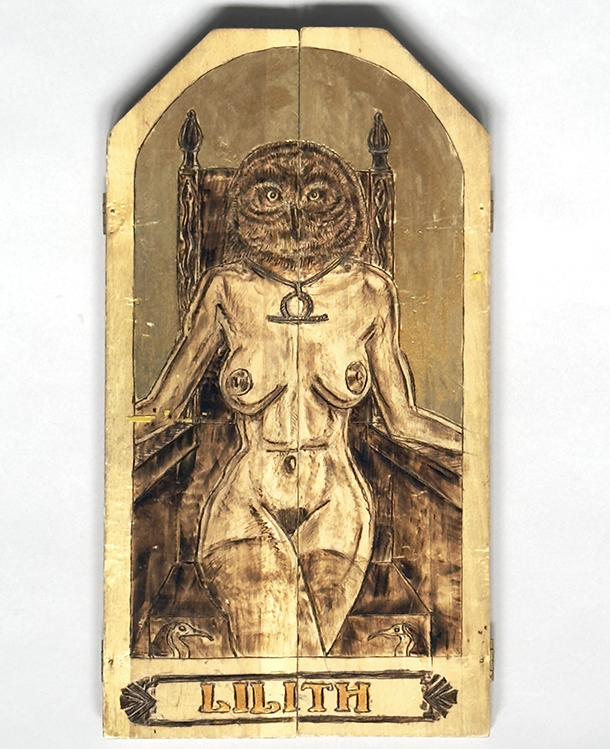

Calhoun’s paintings are intensely erotic and, for some viewers, they might exude an air of something mythical. One of his triptychs is dedicated to Lilith, a figure in ancient Mesopotamian and Jewish mythology who is sometimes depicted flanked by owls.

When I spoke with Grossman, he suggested that, for Calhoun, the eroticism that can be felt in his art might be seen as something more than the expression of sexual fantasy, but also as a way by which the disabled artist could feel connected to a sense of physical power and intimacy that his ailing body and the effects of his war experience had diminished.

Here’s my interpretation of Calhoun’s small, intimate-feeling triptychs: I see them as his private altars.

They’re complex objects that can be opened up to reveal different layers of his imaginary world. To me, his pictures made on bark-edged slabs of wood feel even more primal. Into these pictures he burned scenes of Mayan temples and giant anteaters, as if, in his art, he were trying to transform the traumatic memories of the Vietnamese jungle in which he had fought as a young soldier into landscapes reminiscent of the imagined lands of ancient myth.

When I hold and examine Tancred Calhoun’s strange creations, I realize that they’re not just works of art. For Calhoun, they were the windows he carved into the confining walls of his room so that, finally, he could breathe.

Below: Tancred Calhoun’s depiction of Lilith, a figure in ancient Mesopotamian and Jewish mythology who is sometimes depicted flanked by owls. Here, this goddess appears with the head of an owl. Photo by Steven Hirsch