AN EXHIBITION SHOWS THAT, OUT OF THE SHADOWS, COMES LIGHT

The Horror Show! A Tale of Twisted Britain

Somerset House London

Strand

London WC2R 1LA England

United Kingdom

On view from October 27, 2022 through February 19, 2023

From London, our artist-correspondent Cathy Ward reports:

This year, at Halloween time, The Horror Show! A Tale of Twisted Britain opened at Somerset House, a cultural center known for innovative programming that is located in central London. The works of art in a variety of genres and media that are on view in this remarkable exhibition span a period from the early 1970s until today.

Like the 50th-anniversary edition of the artist Andrew Logan’s Alternative Miss World pageant, which featured fab avant-garde art, costumes, and performances, and took place at the end of October (see my separate article in this issue of brutjournal), The Horror Show! is a cultural event that seems to have sprung from the darkness of today’s dispiriting news from just about everywhere into the light of unbridled artistry and liberated creativity.

As I took in the content, sights, and vibes of these two events, it felt to me, as I thought back to the dreary period of the 1970s in Britain, as though the radical creative energy of a bygone era had been rereleased into today’s atmosphere. Could its impact and effects serve as catalysts for a new generation of artists, inspiring them to strive to keep moving forward even in the face of adversity?

The Horror Show! has been curated by the artists Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard (along with Claire Cattarall, Somerset House’s head of exhibitions). I asked them about the fortuitous, seemingly coincidental timing of the opening of their exhibition and the presentation of Andrew Logan’s Alternative Miss World, which quickly became the hottest, most coveted ticket in London and sold out fast. The production of both of these events had required years of meticulous planning.

In a reply statement, Forsyth and Pollard told me, “We experienced a remarkable rush of hope that week, which has felt out of reach in these politically hopeless times. Both events celebrate resilience and imagination [, which are] two of the very best qualities around.”

The Horror Show! takes its title from the futuristic, Russian-influenced youth slang called “Nasdat” that appears in the British writer Anthony Burgess’s dystopian satirical novel A Clockwork Orange; that book was first published in 1962. Its teenage protagonist, Alex, and his gang of “droogs” (from the Russian word meaning “friends”) revel in carrying out senseless violence. They say “horror show,” a word derived from “хорошо” (transliterated as “horosho”), the neuter short form of the Russian adjective meaning “good,” to express the sense of satisfaction they feel in carrying out their destructive behavior.

Burgess turned his novel into a screenplay before the director Stanley Kubrick himself adapted the British author’s book into a film, which was first shown in New York in December 1971. A copy of Burgess’s script, which was never made into a film, is on view in The Horror Show!, which is filled with references to movies. Both Forsyth and Pollard are artists and filmmakers, and the exhibition they have organized may be seen as a kind of horror mystery viewers are invited to unravel. It is divided into thematic sections whose names, such as “Monster,” “Ghost,” or “Witch” suggest horror-movie characters or scenes.

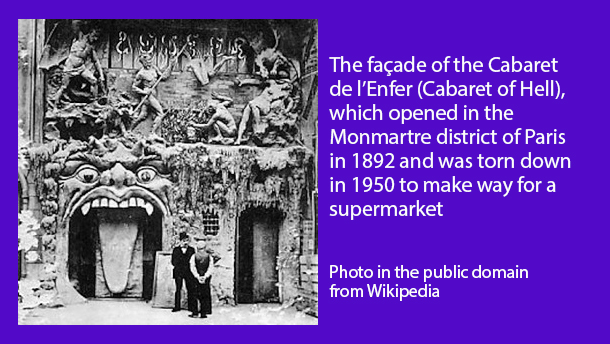

At the entrance to the exhibition, I stepped through a gaping mouth reminiscent of the sculpted façade of the famous Cabaret de l’Enfer (Cabaret of Hell), which opened in the Monmartre district of Paris in 1892 and was torn down in 1950 to make way for a supermarket. I felt as though I was being consumed as I passed through this monstrous orifice and then through the narrow, sometimes suffocating passageways of the exhibition’s layout.

This experience reminded me of the performance artist Marisa Carnesky’s “Ghost Train Project,” which toured the United Kingdom and Europe from 2004 through 2009. As the artist’s website notes, that project “[i]ncorporat[ed] high-end illusions, aerial flying, moving performance sets, a cast of eight and 50 meters of specially-built track.” As an interpretation of an old-style fairground, Carnesky’s “Ghost Train” was a spectacular, theatrical art piece. The artist is represented in the “Witch” section of The Horror Show! by a display case filled with her old-time magic tricks and fairground-performance props.

I moved on through large-chamber galleries whose soundscapes churned with soundtracks from the 1970s and 1980s compiled by the DJ-producer Mark Moore (from the band S’Express) and the DJ and club founder Martin Green. The music helps create an ambiance that evokes the spirits — and brings to mind the gritty bowels — of London music clubs of past decades. On display is a relic of those infamous nighttime venues — the artist Eve Ferret’s lone black sandal, which she purchased from Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s now-legendary, London boutique SEX back in the 1970s; her shoe’s partner was lost long ago after a night of hedonistic pleasure, leaving its battered, time-worn companion to be showcased and immortalized here.

If only a shoe could talk…

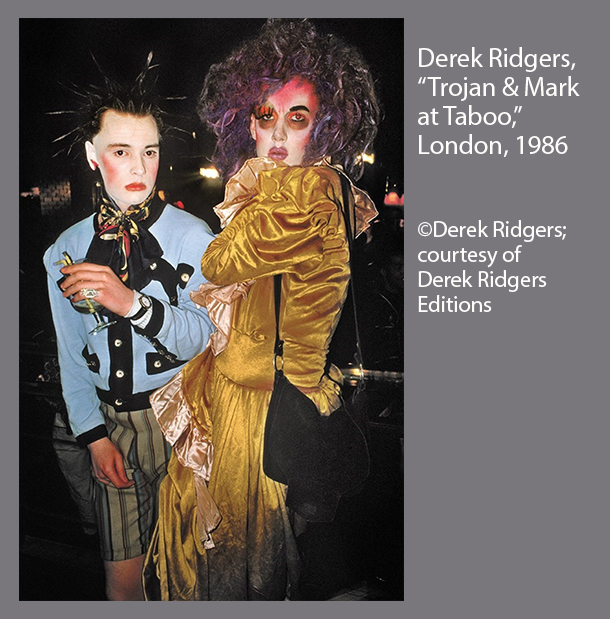

The photographer Derek Ridgers has earned my admiration for the tremendous stamina he has demonstrated over the decades as he has ventured out to explore and document some of London’s edgiest, most inaccessible, most notorious nightclubs. Ridgers would seek out those nocturnal corners in which the nearly comatose lay sprawled out under tables, and lovers lurked in the shadows. He relentlessly captured the effects on clubgoers following nights of frenetic dancing fueled by drink and drugs. His photographs offer an enduring testimony to the subcultures that developed in those dark places, well out of sight of the colorless outside world.

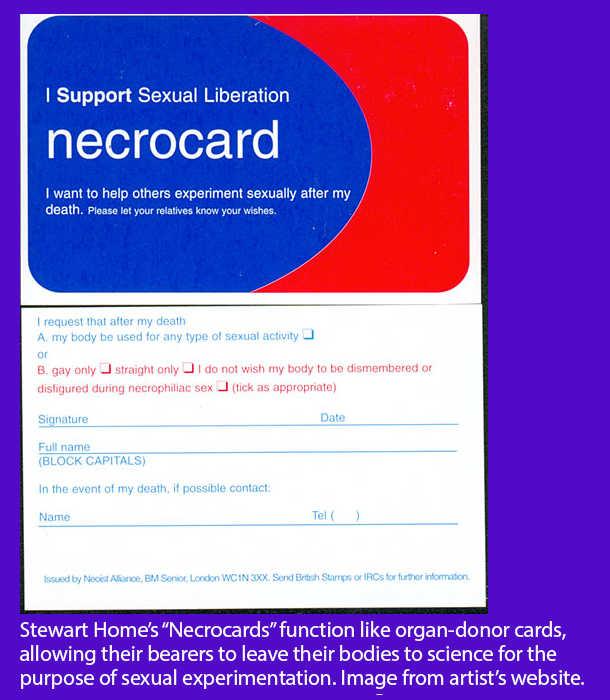

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Stewart Home’s “Necrocards” function like organ-donor cards, allowing their bearers to leave their bodies to science for the purpose of sexual experimentation, and Suzanne Treister’s “Hexen 2.0,” representing an occult belief system in the form of a tarot card deck, illustrates the interconnected histories of the 20th century.

On Home’s own website, describing “Necrocard,” the artist writes: “I decided to issue donor cards enabling those who carried them to leave their bod[ies] for sexual experimentation. Getting the artwork together wasn’t a problem. I simply copied the design of NHS [the National Health Service, Britain’s publicly funded health-care system] donor cards but changed the wording. My necrocards [carry] the legends, ‘I support sexual liberation’ and ‘I want to help others experiment sexually after my death.’ The first two printers I approached refused to do the job. One of them told me later that if they’d realized the card was a joke, and that I wasn’t a necrophile, they’d have printed it for me.”

The British actor Christopher Lee (1922-2015) became well known for portraying Count Dracula in the movie Dracula (1958); he also appeared in such films as the Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Corridors of Blood (1958), Uncle Was a Vampire (1959), and Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), among many others.

Lee also played Lord Summerisle in the director Robin Hardy’s 1973 British folk horror film The Wicker Man, whose story takes place on a remote Hebridean island. In the movie’s climactic scene, Police Sergeant Neil Howie (played by the actor Edward Woodward), a devout Christian and a virgin, too, is burned alive after being shoved inside a monumental human figure made of wicker. Lee’s personal shooting script for the film is included in The Horror Show!, in which the musician and music producer Drew Mulholland also presents a collection of artifacts related to The Wicker Man, including a piece of wood from the original Wicker Man sculpture in which the hapless Howie meets his sacrificial fate.

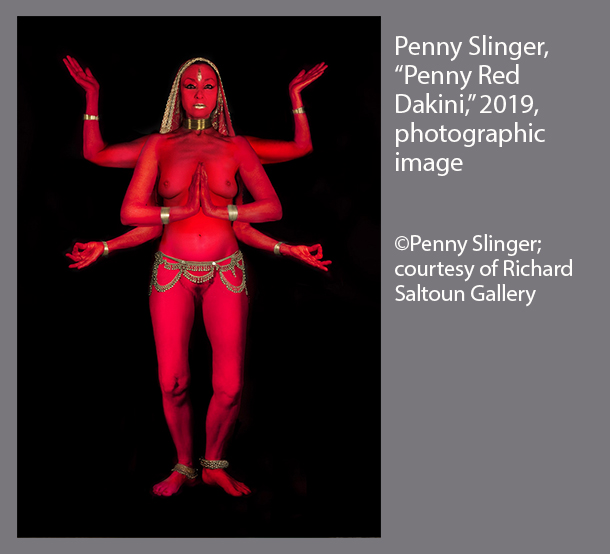

Also on view in The Horror Show!: Harminder Judge’s funny and awe-inspiring “Self Portrait (after Kali & Gene),” a digital C-type print from 2009, in which the artist, who traces his ancestry to the Punjab region, blends a portrayal of the Hindu goddess Kali with that of the bass player Gene Simmons from the rock band KISS, with his emblematic, long tongue sticking out, in a spooky, semi-silhouette; and Penny Slinger’s exceptional, collaged self-identity works, which combine what feel like the mystical qualities of Surrealism and radical, 1970s-era feminism.

In 1978, Slinger’s “Mountain Ecstasy”series of sacred and profane photo collages, inspired by her study of tantric art, provoked controversy. As she writes on her personal website, “Unfortunately, British Customs did not understand the nature of the work and burnt thousands of copies of the Mountain Ecstasy book when they were entering England [, having been sent] from the printers in the Netherlands.” On view at Somerset House: Slinger’s photographic work “Penny Red Dakini,” from 2019.

In the “Witch” section of The Horror Show!, I also came across Juno Calypso’s video work “Honeymoon Suite,” in which a naked young woman can be seen admiring the curves of her green-skinned body in multiple-mirror reflections as she stands in a pink, heart-shaped bathtub. Her bewitching qualities are reminiscent of those of a Star Trek alien life form as she is transformed before our eyes from a mere human into a red-haired, green goddess — now, apparently, dangerously toxic, but still indescribably desirable.

When it comes to political and activist themes, protest and art routinely combine in the consistently powerful work of Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey, two artists who have collaborated since 1990 on projects that aim to raise awareness about environmental issues. On view in the current exhibition is their “TRUTH Grass Coat,” which they first produced over 30 years ago in conjunction with an anti-fur campaign sponsored by the Lynx Educational Trust for Animal Welfare. More recently, this same Ackroyd and Harvey creation has become associated with the save-the-planet campaigns of the U.K.-based groups Culture Declares Emergency and Extinction Rebellion.

The Horror Show! also calls attention to the catastrophic impact over the decades of the HIV/AIDS global epidemic, which began in 1981. The horror of that plague is evoked most resonantly here in Blue, the last film made by the multi-genre artist Derek Jarman (1942-1994), who died at the age of 52 from complications related to AIDS. In Blue, Jarman, in the role of narrator, describes how the disease has destroyed his body, his voice steady as it flows out from a blank, blue screen.

In another display, Jarman’s fingerprints can be found on a book by the English artist and occultist Austin Osman Spare (1886-1956), which he had gifted to John Balance (1962-2004, also known as “Jhonn Balance”), a co-founder of the experimental-music group Coil. That musical ensemble created soundtracks for Jarman’s works. After Balance died, the book he had received from Jarman was passed along to the musician Ossian Brown.

If The Horror Show! interests me — and it does, very much — for its examination of just what, more expansively speaking, “horror” and “horrific” can mean, including references to debilitating diseases; the destruction of the Earth, with impunity, by polluting corporations; and unjust social conditions, I have to admit that I’m also interested in its themes, for, in it, I was invited to present a work of my own.

“Home Rites” (2009), the piece the curators chose, consists of an old table, seven glass domes, and seven corn dollies. The table came from an Edwardian-era house on Downham Road, in East London, in which I lived for many years starting in the mid-1980s. When I moved in, this table already had been standing for some time in a basement kitchen.

Many of the original features of the shabby old house were long gone, its fireplaces having been ripped out and sold for scrap, and its many elegant staircase banisters having been cut up and burned long ago for firewood to keep its inhabitants warm. It was a cold, bohemian place — and for me, it was love at first sight. I stayed there 23 years.

The table that became part of “Home Rites” had stood in the same spot in the house’s kitchen for several decades before I moved in. That was clear from the deep foot-fall impression the table had made, staining the floor. Meanwhile, many of the house’s temporary occupants who had passed through it over the years had left their marks by carving their names into the aged table’s top.

The old, run-down house had been designated by local authorities as a “short-life” dwelling that could be temporarily occupied until the municipal council obtained the funding necessary to renovate it and then allow proper tenants to rent it and move in. During the era of the Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher, such houses were left to rot, as funds for fixing them up either were not available or were withheld by the government. During the time we lived in the house on Downham Road, my companions and I acted as its custodians, paying a small rent. In effect, though, we were not much more than squatters.

Still, I felt a sense of proprietorship about that kitchen table and I would not allow it to leave the house until or unless I knew I was going to be rehoused. For me, it had been transformed into a kind of talisman by all the people who had carved their names into its surface, including many whom I had known and with whom I had resided in the old house. That table possessed some kind of power.

As for the corn dollies, which are made of woven wheat: They’re the product of an old British folk custom, in which farmers, after harvesting their last wheat crops of the season, would create such symbolic objects and then bury them in the earth in the hope of prompting bountiful future harvests.

I designed the corn dollies that appear in “Home Rites” after I was permanently rehoused in 2007 as a political statement alluding to everyone’s right to decent, affordable housing, as well as to the housing concerns of migrants, refugees, homeless people, and less well-off members of society. My corn dollies also refer to the basic custom of human beings gathering at a table to “break bread” — to eat and nourish themselves — and, more broadly, to the notions of safety and security.