NOW 82 YEARS YOUNG, AN AMERICAN ART-MAKER CONTINUES HIS CREATIVE JOURNEY

by Edward M. Gómez

In the stories of some artists’ creative journeys, sometimes it may seem that art finds them just as much as they discover the power and allure of art and then commit themselves to the artist’s life. They choose to make the production and presentation of their original creations their lives’ work, both for their own expressive purposes and as a means of engagement in the ideas and issues of their times.

Howard Saunders (Instagram: @hauihudson), who is now in his early eighties and has been based in Brooklyn, New York, for the past eight years, is an artist whose involvement with art has been deeply entwined with his life’s experiences, including a formative period of military service, decades ago, that played a significant part in shaping his worldview.

Many of the works of art he has made in recent years — drawings on paper in various media, often incorporating collage elements — reflect his outlook. As those he has shared with us in conjunction with this month’s “Make art, not war” theme demonstrate, they allude to certain kinds of political or historical events or to ways of thinking that time and time again have contributed to the toxic mix of misunderstanding, miscommunication, bad attitudes, and reckless profiteering that has fueled many a war.

Saunders served in the military at an interesting time, when Cold War tensions were reaching a peak in the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962. It was also the period leading up to the introduction, in 1965, of active United States combat units in Vietnam.

After dropping out of college in 1961, Saunders joined the U.S. Navy Reserve, was sent to a naval base near San Diego, California, for training, and then was stationed with a fighter squadron on the U.S.S. Midway, an aircraft carrier that for many years was the largest ship in the world; it was decommissioned in 1992.

During Saunders’ deployment, the Midway plied the seas of Southeast Asia. As a draftsman and illustrator, he created maps for fighter pilots in preparation for the CIA-led, so-called secret war in Laos, which began in 1964. From that year through 1973, U.S. forces dropped more than two million tons of ordnance on Laos, ostensibly to prevent a communist takeover of its government and ultimately making that landlocked state the most bombed country in history.

After leaving active duty in 1964, Saunders remained a Navy reservist for a few more years. Through 1968, he enjoyed a successful career in advertising. Later, he contributed illustrations to Psychology Today, a new magazine at that time that set out to explore a subject of great interest to a mass audience in an accessible manner unlike that of specialized academic journals. In the early 1970s, in San Francisco, Saunders helped establish the Public Media Center, a nonprofit organization that did advocacy work on behalf of social-justice, public-interest, and environmentalist causes.

He also became involved in the nonprofit group Vietnam Veterans Against the War, which had been founded in 1967 to oppose the U.S. government’s policy regarding and American military participation in the Vietnam War. Later, in New York, Saunders continued his work for progressive causes by becoming involved with the Institute for Labor Education, where he produced documentary videos, designed posters, and created cartoons. In the late 2000s, as his multifaceted career wound down, and he eased into his retirement years, Saunders began devoting more of his time and attention to his own art-making.

About his trajectory as an artist, Saunders recalled, “I learned about collage by making photomaps [for American pilots heading into Laos in the early 1960s] using photos that had been shot by 70mm cameras mounted on their fighter planes, replacing the gunnery. I’m interested in the German Expressionist artists, many of whom served on the front lines in World War I and, to me, are heroic beyond comprehension. I don’t know how, if at all, their art affected their constituencies. I didn’t become aware of their work until the late 1960s, which was roughly the same time I discovered ‘The Disasters of War,’ the series of etchings the Spanish artist Francisco Goya produced between 1810 and 1820.”

Later, in 2016, during a trip to the Netherlands, Saunders learned about the bold paintings of the post-World War II CoBrA artists at a museum in the city of Amstelveen dedicated to their avant-garde movement.

As someone who freely combines figurative drawing and painting with a variety of collage elements and media, in his work Saunders shows that he has assimilated influences from the artists whose ideas and techniques he admires. They include, among others, Ray Johnson, Philip Guston, Sue Coe, Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, and Louise Bourgeois. All of these artists are known for their technical inventions and for the candor with which their art addresses its subjects, from political issues to the deepest — and sometimes deeply disturbing — stirrings of the human psyche.

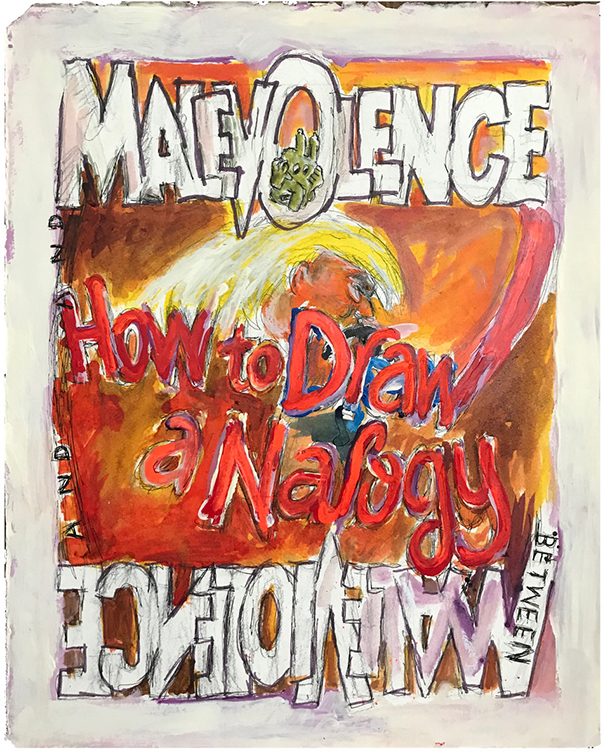

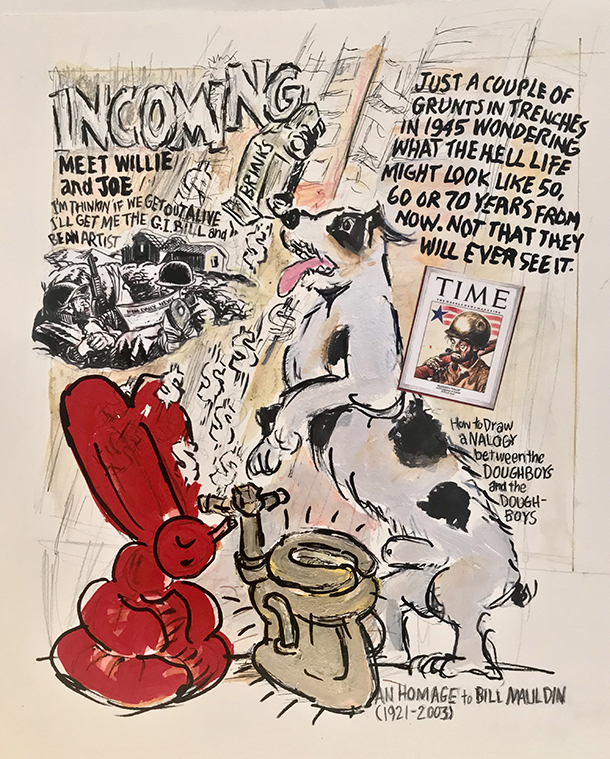

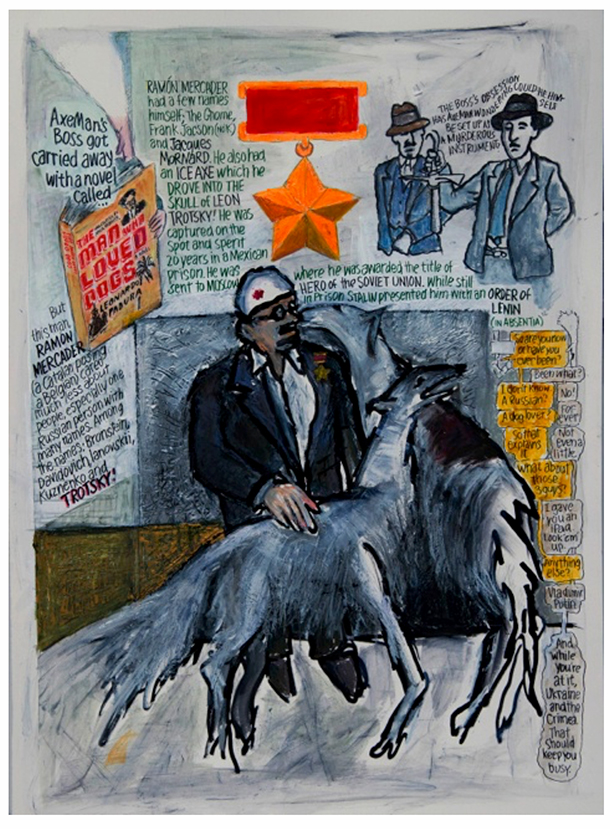

Saunders’ art offers a roller coaster ride of wildly different subjects. One picture recalls the story of Ramón Mercader (1913-1978), a Spanish communist who, in Mexico, in 1940, using an ice axe, killed the Russian Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky (to the delight of the leaders of the then still-young Soviet Union). Another Saunders work pays homage to the editorial cartoonist William (“Bill”) Mauldin (1921-2003), whose Pulitzer Prize-winning images of Willie and Joe, two weary but dutiful World War II infantrymen, became popular among American soldiers and the general public.

Saunders’ “Mueller Flew the Coup” (2021, acrylic, ink on Arches paper) calls attention to the inefficacy — or utter uselessness — of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s 2019 Report on the Investigation Into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election, which reacted with less than a slap on the wrist to Donald Trump’s theft of the electoral contest that gave control of the federal government to his criminal, white-supremacist regime.

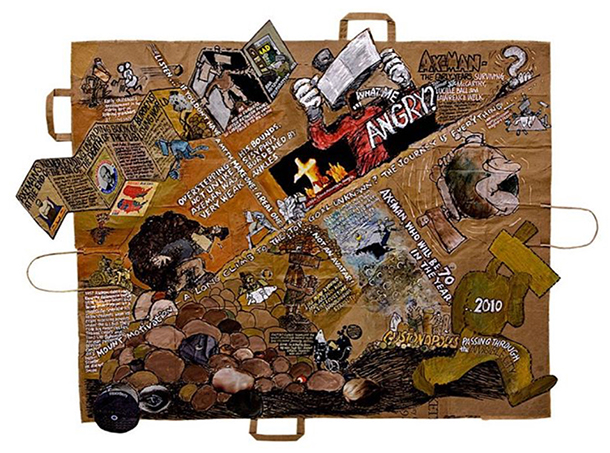

“Born on Bags” (2009), a mixed-media work made with pasted-together supermarket bags, features references to “Axe Man,” Saunders’ alter ego, and recalls various phases of the artist’s life journey.

All of his art is informed, however explicitly or more obliquely, by his experiences as a young man in the military, where he began observing the uses and abuses of power, and by his work as an activist primarily dedicated to social-justice causes.

Speaking with the voice of experience after many decades following the antics and chicanery of military commanders, political leaders, and corporate honchos, Saunders noted in a recent message in response to this issue our “Make art, not war” theme and the follies — and profound, abundant injustices — of our time, “Lately, the idea itself of war crimes has given me pause. War is a crime. Only the winners in war get to make the judgments, but [overall,] this is becoming more interesting to engage with as an artist.”