A CULTURAL HISTORIAN RECALLS THE OBJECTIVES AND ETHOS OF AN ALTERNATIVE RELIGIOUS MOVEMENT WHOSE PARTICIPANTS TOOK IT VERY SERIOUSLY

Daniel Wojcik, a professor at the University of Oregon in Eugene, is a specialist in folklore, mythology, and religious culture. His research has also looked at unusual social-cultural customs, events, and practices, and at the work of certain outsider artists. He is now assembling a new book, Artist as Astronaut: The Otherworldly Art of Ionel Talpazan, which will be published in the near future in the United Kingdom by Strange Attractor and distributed in the U.S.A. by MIT Press. It will recall the life of a Romanian-born outsider artist who made paintings and sculptures depicting unidentified flying objects; Talpazan died in the U.S.A. in 2015.

Wojcik is the author of Punk and Neo-Tribal Body Art (University Press of Mississippi, 1995), The End of the World as We Know it: Faith, Fatalism, and Apocalypse in America (New York University Press, 1997), and Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma (University Press of Mississippi, 2016), among other works.

by Daniel Wojcik

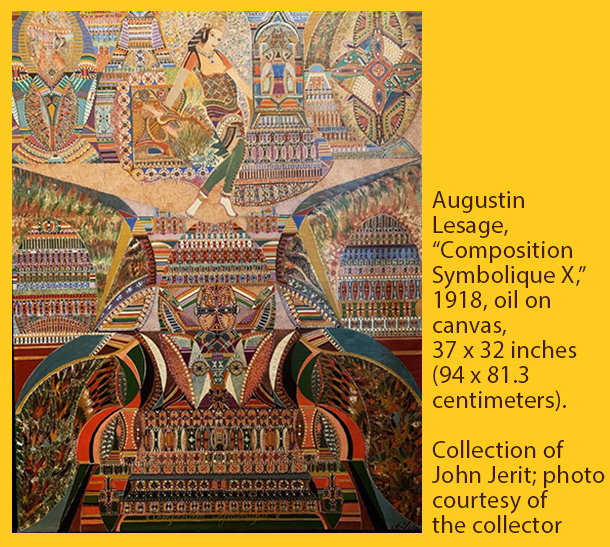

Starting in the 1940s, the majority of the individuals whom Jean Dubuffet initially cited as representatives of art brut creativity were patients at psychiatric institutions in Europe. However, a number of other artists he favored were involved in the Spiritualist movement and participated in the practice of mediumship, including such now-classic outsiders as Madge Gill, Augustin Lesage, Laure Pigeon, Jeanne Tripier, and Raphaël Lonné.

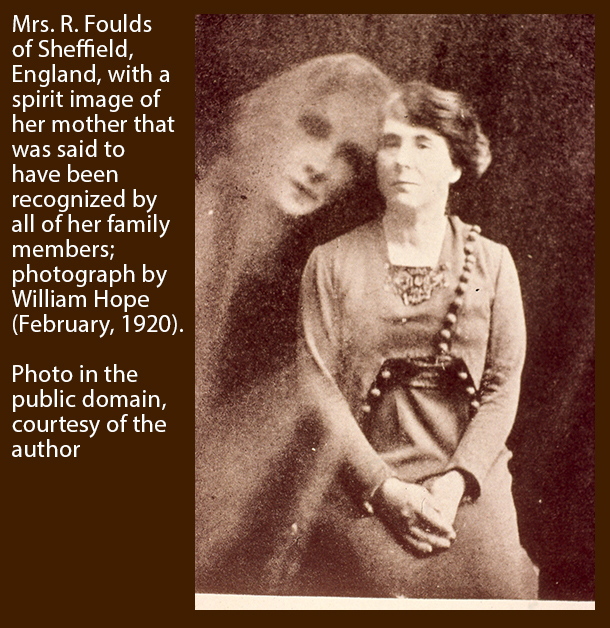

Although the art of these Spiritualists sometimes is viewed as a peculiar or semi-psychotic expression of subconscious states of delirium, these self-taught artists all worked within the context of an alternative religious movement that emerged in the 19th century and emphasized communication with spiritual realms. Trance states and visionary experiences were central to Spiritualism, the beginning of which is usually traced to the spirit messages recorded by the Fox sisters in Hydesville, New York, on March 31, 1848, although some historians have shown that the movement had multiple origins and influences, including the ideas of the Swedish theologian and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) and the German physician Franz Mesmer (1734–1815).

Spiritualism developed into a global religious phenomenon, attracting millions of followers from all levels of society in the United States, Latin America, and Europe.

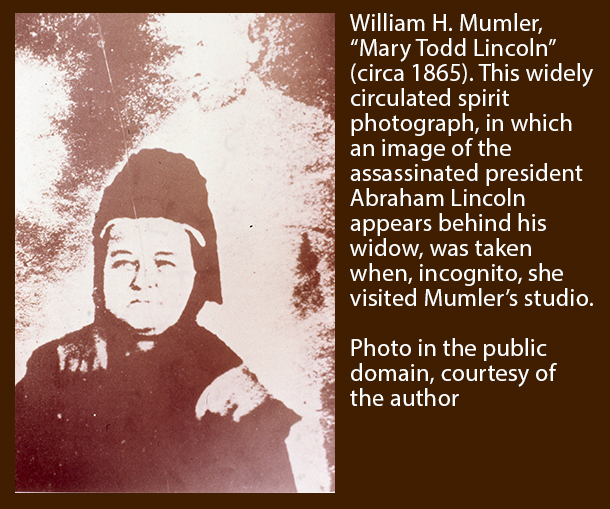

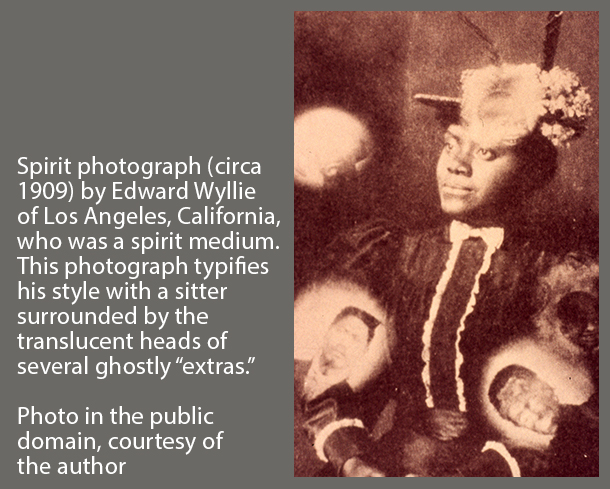

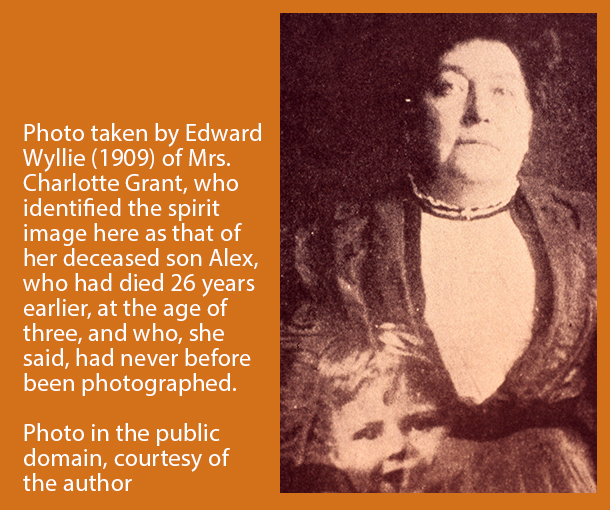

Spiritualism’s practices initially focused on attempts to contact the spirits of the dead, and the mediumistic artworks produced by followers of the movement that became so central to early conceptualizations of outsider art may be viewed not only as artistic expressions but also, as they were in their time, as evidence of successful communication by mediums and séance participants with other realms.

Such works expressed visions of other worlds or conveyed messages and artistic designs whose creation supposedly had been guided by the spiritual intervention of departed loved ones or transcendent beings, who were often referred to as “spirit guides.” The individuals who produced such works generally did not attribute their production to their own abilities but instead regarded themselves merely as physical vessels or vehicles who had performed creatively under the control of the spirit world.

Although Spiritualism developed within the framework of Western Christianity, it often appealed to people who were dissatisfied with established religion. In the United States, for example, thousands of local Spiritualist “home circles” emerged, offering experiential confirmation of the afterlife through personal encounters with spiritual spheres and providing comfort to the bereaved.

Although feminist and reformist concerns were significant aspects of the movement, the unifying and primary principle of early Spiritualism was its belief in the possibility of contact with the spirit world as evidence of the immortality of the human soul (in the Christian sense of that word). In the Spiritualist worldview, souls in the afterlife are believed to evolve and progress through successively higher spheres of spiritual existence. These elevated souls may then mediate between visible and invisible realms and provide knowledge and moral guidance to human beings.

Special emphasis was placed on direct and numinous experiences in the séance room and the ability of selected mediums, usually women, to contact departed loved ones through rituals and revelatory experiences. The Spiritualist movement emerged during a time of increased tensions between religion and science and empiricism; followers seemed to mediate these tensions, often adopting scientific concepts and terminology to formulate a liberal theology based on Christian notions of the afterlife.

Madge Gill (1882–1961) is often regarded as a definitive outsider artist; Dubuffet and other promoters of the art genre for which he invented a name, “art brut” (literally, “raw art”), enthusiastically championed her work. A practitioner of Spiritualism, Gill was inspired to create her works of art during periods of grief and trauma, and produced her substantial oeuvre in a seemingly hypnotic state. André Breton, Surrealism’s leader and main theorist, celebrated the works of Gill and other Spiritualists not so much for their stylistic aspects but rather as expressions of non-rational creative forces — of unbridled creativity, free from restrictive societal conventions.

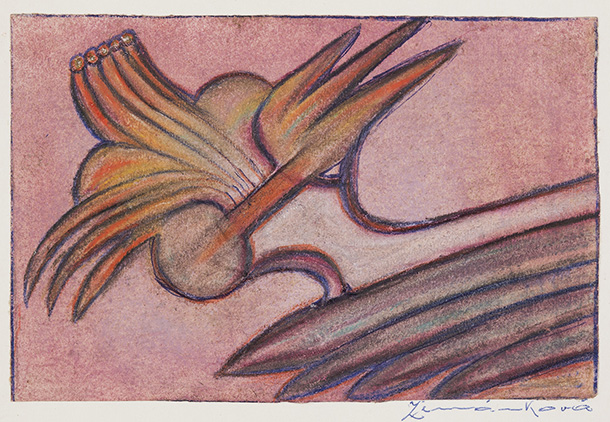

For artists like Gill, the creative process and trance experiences triggered by art-making may provide not only respite from the pressures of daily life and offer sources of healing; they may also serve to help transform a person and provoke experiences of religious ecstasy or elation. The self-taught artist Anna Zemánková (1908–1986), for instance, who was born in Moravia (in what is now the Czech Republic), took up drawing at the age of 52 during a period of depression and later said that she created her work in a joyous, exalted state.

While working on her drawings each day in an apparent trance, in the very early morning, before beginning her daily household chores, Zemánková felt liberated from her emotional burden. She listened to classical music as she drew her swirling, lush depictions of imaginary flora and once declared that her colorful pictures actually drew themselves, seemingly guided by spirits.

The art of Gill and other famous Spiritualists that was created in trance states is captivating and often mesmerizing, but it is not anomalous. Thousands of people produced drawings, writings, and other supposed manifestations of supernatural presences within the context of the Spiritualist movement. The writer Victor Hugo made mediumistic drawings; so did the French dramatist Victorien Sardou (1831–1908) and Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831–1891), a Russian writer who co-founded the Theosophical Society in 1875.

Other known mediumistic artists include Georgiana Houghton, Anna Mary Howitt, Elizabeth and Mary Bangs, Hilma af Klint, Heinrich Nüsslein, Fleury-Joseph Crépin, Margarethe Held, Marjan Gruzewski, Marian Spore Bush, Maria-Faustina Stefanini, Agata Wojciechowsky, Fernand Desmoulin, Helen Butler Wells, Gertrud Emde, Miloslava Ratzingerova, František Jaroslav Pecka, Karel Havlíček, Paulina Peavy, Henriette Zéphir, and Hélène Smith (a late-19th-century and early-20th-century Swiss medium whose real name was real name Catherine-Elise Müller).

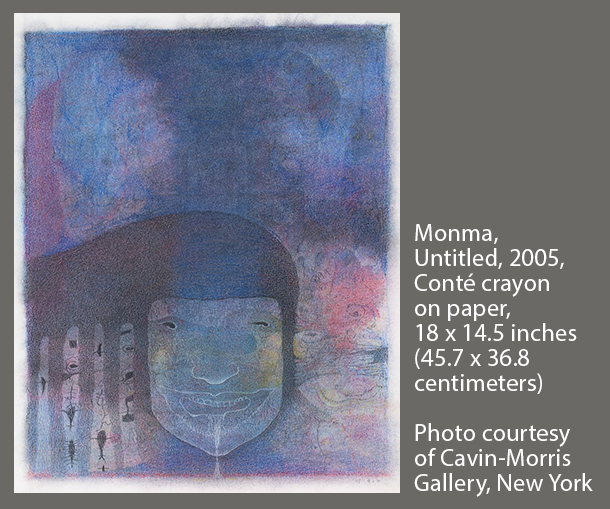

Today, art in the mediumistic tradition is still being made by such individuals as the Japanese artist Monma (born 1951), who comes from the far north of Japan and believes that a force he calls an “entity” guides his hand in his creation of multilayered, dreamlike, ghostly drawings, and the French artist and healer Marie-Jeanne Gil (born 1942), who has produced hundreds of vibrant images. Their creation, she has said, is guided by “beings of light.” Her works depict spiritual beings, celestial lights, apparitions of Christianity’s Virgin Mary, and other supernatural presences.

For Madge Gill and other artists who produced drawings in keeping with the beliefs of the Spiritualist tradition, their activities amounted to more than just creating art. For them, their work served as a mode of communion with departed loved ones and spirit entities who, they believed, provided guidance from higher levels of existence, imparting worldly or spiritual direction.

Their trance states and artistic endeavors sometimes served to shield them from earthly sorrows. They also offered them opportunities to join communities of like-minded believers and to personally make contact with otherworldly realms through engagement in a what may be called a vernacular religious or spiritual system of meaning that addressed issues of existential concern.

to read the whole article.