TOKYO OPERA CITY ART GALLERY SHOWCASES THE CREATIVITY AND INSIGHTS OF ONE OF CONTEMPORARY ART’S MOST ORIGINAL THINKERS

Published on January 29, 2026

“ALFREDO JAAR: YOU AND ME AND THE OTHERS”

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

Tokyo Opera City, third floor

3-20-2 Nishi-Shinjuku, Shinjuku-ku

Tokyo-to 〒163-1403 JAPAN

Telephone: (81) 050-5541-86

by Edward M. Gómez

TOKYO — Visionary artists are creators who not only look at the world and their subject matter in a fresh, engaging, often groundbreaking manner, but who also regard the communicative power and the purposes of art in ways that expand and enrich those essential attributes of their métier.

Many years ago, in New York, the pioneering, influential American graphic designer Milton Glaser (1929-2020), who became famous for his “I ❤ NY” logo and his Bob Dylan poster (1966), told me, “It’s a good artist who catches our attention and entertains us. It’s a great artist who changes the way we see.”

Glaser was referring to his friend Jean-Michel Folon (1934-2005), the Belgian artist who was known throughout the world for his delicate watercolors packed with clever visual puns. The indelible images Folon conjured up in his resonant works of art exude a deep sense of humanity along with a gentle sense of humor.

All of these thoughts about the functions, character, purposes, and expressive power of art came vividly to mind last week at the opening of the new exhibition “ALFREDO JAAR: YOU AND ME AND THE OTHERS.” It’s being presented at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery in the Hatsudai neighborhood of west-central Tokyo. Despite its name, this venue is a public, noncommercial institution, not an art-selling gallery. Its just-opened exhibition, which features a selection of 21 works in various media and genres by the Chilean-born artist, photographer, architect, and filmmaker Alfred Jaar, will remain on view through March 29.

Jaar, who was born in Santiago de Chile in 1956 and, in the early 1980s, moved to New York, was present at the opening of his Tokyo exhibition, his first-ever solo presentation of his work in such quantity and in such a setting in Japan. He told me that, lately, he has been based in Portugal, and that, instead of regarding this exhibition as a retrospective — the earliest works on view date back to the early 1970s — he prefers to think about this rather comprehensive survey as “an anthology” of his art-making and thinking as they have developed over the decades of a long career.

In the past, in various museums’ collections and in numerous, multi-artist, thematic exhibitions, I had encountered memorable examples of Jaar’s work, but for me, “YOU AND ME AND THE OTHERS” offers an opportunity to examine and get to know this artist’s ideas and artistic expressions in a concentrated and very rewarding way. With Jaar’s active involvement, the exhibition has been organized by Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery’s senior curator, Osamu Fukushi, and his curatorial colleagues. In recent years, their imaginative, museum-quality programming has made Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery one of the most interesting visual-arts venues in the Japanese capital. Its publications program, which produces attractive, substantive exhibition catalogues, is also noteworthy.

Today, at a time when the rot of criminality, corruption, authoritarianism, and greed has infected governments and political institutions around the world, and many mainstream, so-called news media have cowered in the face of, caved in to, or willingly embraced such forces, Jaar is an artist who continues using his work to illuminate various forms of injustice, wherever they may have developed and emerged.

Jaar’s work is inherently political but never in a partisan way. He is not a self-appointed spokesman for any causes, and, in his art, he is never a polemicist. Instead, through his work, he dares to explore a subject that, nowadays, normally, is rarely examined without many observers allowing their considerations of it to deteriorate into sloganeering, mock “argument.” That subject is the fundamental meaning, function, and impact of that which is political and, by extension, of that which is just or unjust.

As a thinker, art-maker, and engaged citizen of the world, Jaar creates art that is informed by and reflects the multifaceted, often confounding nature of politics in its most basic sense: politics as the entire, complex system or network of relationships, communications, and interactions between human beings living and working in a particular society.

Very often, the subjects of Jaar’s works refer to specific events, beliefs, or attitudes in a particular place, but his art almost always transforms a focus on the local to an appreciation or assessment of an idea or a cultural, economic, or political value as it is expressed or manifested in tangible ways on a global scale.

Like the most notable artworks of any time or place, each of Jaar’s image-based, mixed-media, or viewer-participatory productions serves at the same time as a cogent examination of a particular subject and as an essay in the form a work of art can take and in the ways by which it can communicate.

As the range of works on view in “YOU AND ME AND THE OTHERS” shows, over the years, Jaar has developed a distinctive mode of making art that combines aspects of design, minimalist aesthetics, journalistic reporting, mixed-media spectacle, sociological investigation, philosophical thinking, and other sources. Often, Jaar’s works may seem puzzling at first, only to reveal their potent meanings or messages after a viewer’s brief moment of quiet reflection.

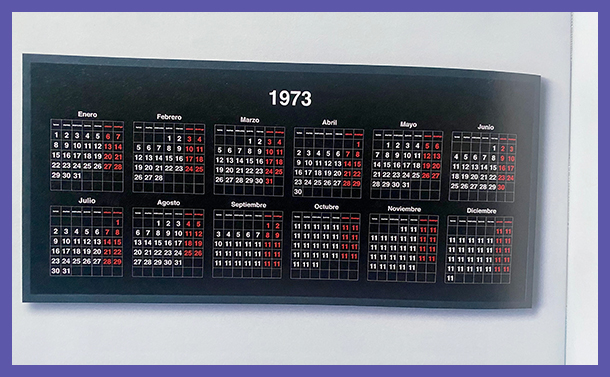

The current Tokyo exhibition features several emblematic examples. One of the earliest works on view is “September 11, 1973” (1974), a printed calendar displayed in a black frame. The calendar presents the months and days of the year 1973 in their usual, sequential order, but after the date September 11, 1973, all of the remaining days of the year are marked with the number 11.

That’s because, in the days, weeks, months, and years following the Chilean general Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état, which took place on September 11, 1973, toppling the elected government of the socialist president, Salvador Allende, Chile’s democracy died.

The United States of America, which had helped destabilize Chile’s economy and covertly funded Allende’s political opponents prior to Pinochet’s coup, officially recognized the military junta he installed, which went on to rule the country for 17 years.

It’s only when a viewer recalls the big event of September 11, 1973 in Chile’s history or learns about its significance that the meaning of Jaar’s otherwise nondescript calendar, with its clean, simple, modern graphic design, suddenly hits hard. This kind of one-two punch, deployed with a perfect sense of timing, is a hallmark of Jaar’s art.

As the exhibition’s catalogue notes, the artist’s “Welcome to the USA (TIME),” an inkjet-ink-on-paper piece from 2018, “belongs to Jaar’s ongoing ‘Press Works’ series, in which he intervenes in the circulation of mass-media imagery to expose its ideological framings.” In this work, Jaar alters the headline that appears on an issue of TIME, the American newsmagazine, that was published in 2018, during Donald Trump’s first term as the occupant of the White House. The magazine’s cover photo shows Trump confronting a crying Honduran girl at the USA-Mexico border, an image that symbolized the Trump regime’s family-separation policy affecting migrants who had illegally entered the United States.

Given the political context to which it referred, TIME’s cover headline, “Welcome to America,” was meant to sound bitterly ironic. Here, though, Jaar strikes out the word “America” and replaces it with “the USA.” His point is a powerful one: The United States has never been “America.” As a notion and a place name, “America” is merely romantic or poetic, like the long-outmoded term “Albion,” meaning Britain. The idea that citizens of the USA hold of “America” is a fantasy; what is refers to is something imagined, not an actual place on a map.

The geographic territories that do appear on maps are the Americas, plural — North America, Central America, and South America, each of which is made up of numerous countries. Contrary to the collective, even arrogant assumption of the United States’ “Americans,” in the Western Hemisphere, no one country alone can lay claim to the moniker “America.”

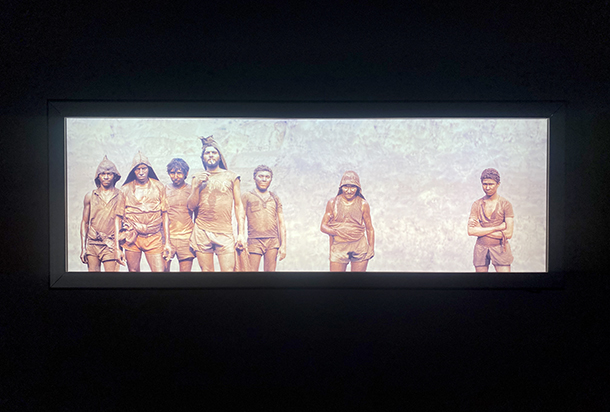

In “Gold in the Morning,” a group of color photographs presented in various formats — as framed prints, on wall-mounted lightboxes, or in mixed-media installations incorporating lightboxes — Jaar documents the backbreaking physical labor of thousands of miners at Serra Pelada, an enormous, open-pit gold mine in Pará, a state in northern Brazil.

Jaar began taking photos there in the 1980s. Although shot in color, his photos, with their nearly naked subjects dressed in dirt-soaked shorts and T-shirts, resemble old sepia-toned prints. The dramatic sense of disparity viewers may discern in such images lies between the humility of these Brazilian miners and the wealth they hope to enjoy should they ever discover some precious nuggets of gold.

Jaar continued developing his “Gold in the Morning” series over a period of many years. At one point, he displayed some of his photos of the Serra Pelada miners in New York City’s subway, along with international gold-price indices, thereby calling attention to the economic circuits that link the drudgery of legions of anonymous Brazilian laborers with the value of a coveted commodity on global markets.

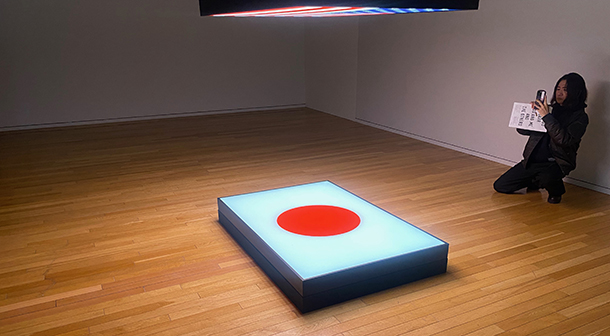

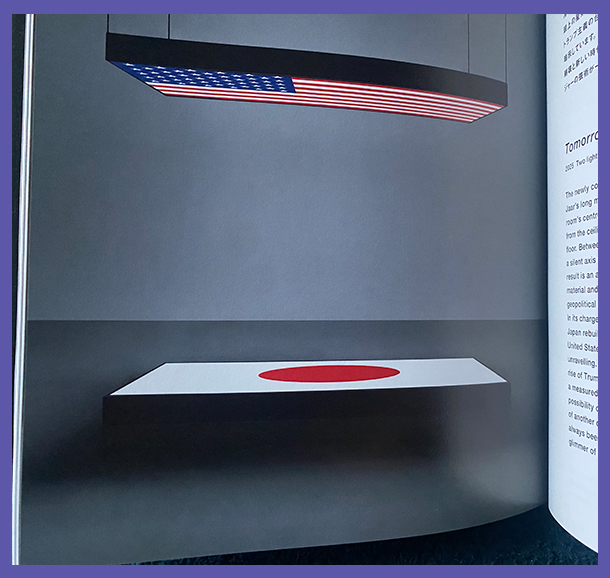

In, “Tomorrow is another day” (2025), a new work that was commissioned for the current exhibition at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, Jaar suspends a large lightbox displaying the national flag of the USA directly above a lightbox of the same size featuring the flag of modern Japan, which lies flat on the floor. Physically, the two flags meet in a luminous, aesthetic face-off exuding the silence and serenity of a Zen temple’s rock garden.

About this new work, the exhibition’s catalogue notes that this encounter — or confrontation — of the flags of two countries that were warring adversaries almost a century ago evokes a sense of “a silent axis of tension” that can be felt as “holding the space in a state of fragile equilibrium.”

Given that, today, with the presence of more than 50,000 U.S. armed-forces personnel and more than a dozen American military bases on Japanese soil, Japan remains an occupied country, Jaar’s broodingly elegant, flag-meets-flag moment is redolent with allusions to history and to the dynamics of global power politics.

“YOU AND ME AND THE OTHERS” concludes with a reprise of a large, mixed-media spectacle of a video-based work, “Hiroshima, Hiroshima,” which Jaar created for his Hiroshima Art Prize exhibition in 2023. As described by the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, which administers the Hiroshima Art Prize, that award, which was established by the city of Hiroshima in 1989, “recognizes the achievements of artists who have contributed to the peace of humanity through art.”

Through its appreciation of such art-makers’ creations, the prize, which is bestowed every three years, aspires “to spread the Spirit of Hiroshima, which wishes for a peaceful world free from nuclear weapons.”

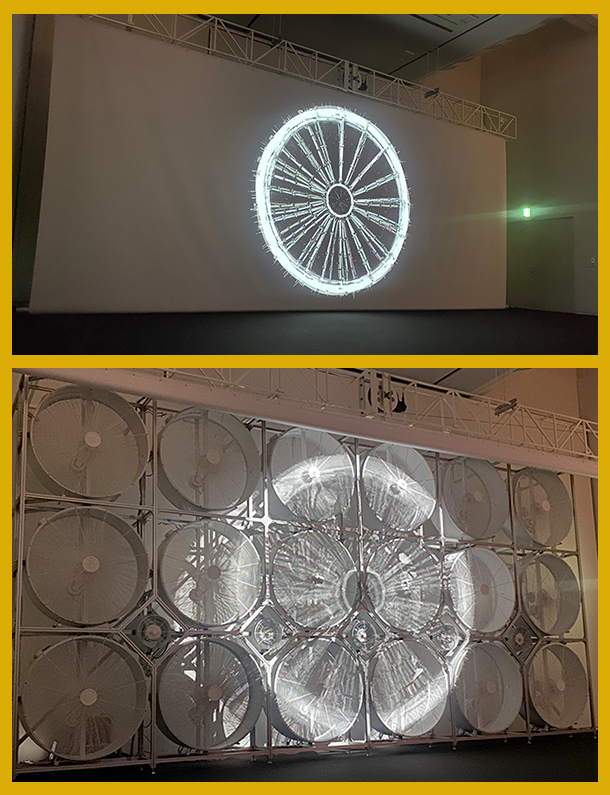

“Hiroshima, Hiroshima” is presented in a dark viewing room equipped with a screen covering one entire wall. The video opens with an aerial view of Hiroshima, in southwestern Japan, and the camera’s bird’s eye view sweeping slowly over the city’s rivers until it arrives directly above the ruins of the building that is known today as the Atomic Bomb Dome.

Now a UNESCO World Heritage site, it is, as UNESCO’s website explains, “the only structure left standing in the area where the first atomic bomb exploded,” on August 6, 1945. The ravaged building, UNESCO notes, “has been preserved in the same state” in which it was left “immediately after the bombing,” and today serves as “a stark and powerful symbol of the most destructive force ever created by humankind” while also “express[ing] the hope for world peace and the ultimate elimination of all nuclear weapons.”

In “Hiroshima, Hiroshima,” Jaar’s airborne camera hovers over the carcass of the Atomic Bomb Dome, its neutral eye taking in the round shape of the ruined top of the old building, which, with the scraps of its support structure exposed, resembles a wheel and its spokes. This full photographic, aerial view slowly fades and transforms itself into a plain, white-on-black reproduction of the round rim of the top of the building, which in turn becomes a simple, geometric, wheel-and-spokes motif.

Suddenly, this round shape begins to spin, and its movement grows ever faster, alarmingly, like the out-of-control part of some high-powered machine. And then — pow! — the projection screen rises like the curtain in a theater, a torrent of rumbling sound is unleashed, and a wall-high stack of huge, roaring industrial fans surprise this video work’s viewers in the dark with the unsettling force of a sensory assault. Jaar’s gentle-to-fierce-feeling spectacle offers a bracing, symbolic evocation of the suddenness and daunting impact of the atomic bombing that destroyed most of Hiroshima in August 1945.

Stepping out of the pitch-black viewing room and making my way down the gallery’s main corridor toward the storage lockers in which I had left my overcoat and book bag, I felt intellectually and emotionally numb — and also very angry.

Jaar’s ingenious use of a relatively simple combination of the technological tools available to him today to conjure up such a powerful reminder-warning about humanity’s capacity, in its most thoughtless, reckless, antagonistic moments, to stupidly destroy itself, felt chilling. That an artist can express such a big idea with such compassion, drama, and, yes, grace (in Jaar’s respectful nod to history and the captivating rhythm with which “Hiroshima, Hiroshima” unfolds) may be seen as a creative tour de force.

That such a spectacle can — and does — serve as a reminder of how stupidly and dangerously violence-worshipping, war-mongering, corrupt political leaders everywhere continue to think and act, putting the lives of masses of people all around the world at risk, is noteworthy, even laudable. It’s what this potent message reminds us about that form of power-mishandling injustice, which continues to inform and shape geopolitics and, ultimately, affect all of our everyday lives, that can and should make viewers feel more than a little upset about the state of the world.

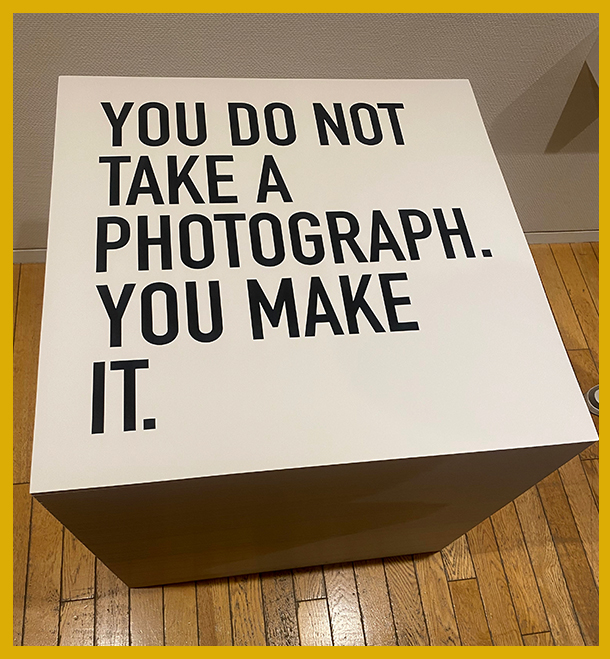

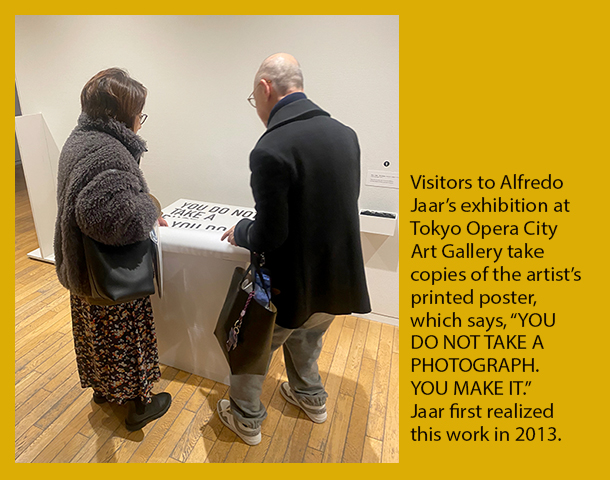

As visitors to “YOU AND ME AND THE OTHERS” leave the gallery, they’re invited to take a sheet from a stack of posters on which Jaar has printed, in large black letters on bright white paper, “YOU DO NOT TAKE A PHOTOGRAPH. YOU MAKE IT.” This remark, which has been attributed to the American photographer Ansel Adams (1902-1984), and which Jaar revives in this audience-participation work of art, invites viewers to reflect and consider the roles they play in shaping what they see, perhaps not only when composing and snapping photographs, but also when observing the world in general.

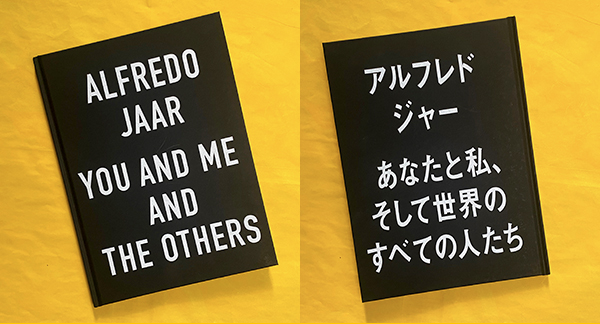

About this work, the exhibition’s catalogue notes, “A photograph, [Jaar] reminds us, is never a neutral window onto the world, but a constructed threshold through which the world is continuously reimagined.” (By the way, the catalogue that has been published to accompany “YOU AND ME AND THE OTHERS” is excellent. Jarr oversaw the book’s production; its texts introducing the exhibition’s themes and describing the various works on view were written by Shino Nomura and Koichiro Osaka.)

At the opening of the exhibition, I asked Jaar why it is that, despite all the very urgent crises that are unfolding around the world today, it often seems that many or even most contemporary artists are not finding ways to address them in their work, if not directly in the way, say, a history painter might attempt to do, then perhaps metaphorically by tackling such big, immortal themes as life, death, power, or hope.

Jaar did not need much time in which to gather his thoughts and respond. It was obvious to me that my question touched upon a tendency in the art world he had noticed, too.

He replied, “If art isn’t at least 90 percent critical, it probably isn’t doing its job, and, in that case, what is it if not just decoration?”