FROM THE VASTNESS OF THE SKY TO THE DELICATE THROB OF A HUMAN PULSE, THE NATURAL WORLD ALL AROUND US — OF WHICH WE ARE A PART — OFFERS COUNTLESS SUBJECTS TO PORTRAY AND TO EXPLORE

by Edward M. Gómez

From the annals of ancient pop-culture history come memories of the American margarine brand Chiffon’s TV commercials of the 1970s, in which the accomplished film and television actress Dena Dietrich (1928-2020) probably achieved her greatest fame. Dressed in a flowing white frock while gliding through verdant forests to greet chirping birds and savor the splendor or her bounty, her head topped with a crown of flowers, Dietrich played a not-to-be-duped Mother Nature, cheerful and smiling at first, but angry and threatening when challenged.

In those now-classic ads for Chiffon’s soft-spread product, which came packed in plastic tubs, an off-camera announcer offers Dietrich a taste of what she assumes is her own “sweet, creamy butter,” made with the milk of her pride cows. When informed that the tasty goop she is sampling is, in fact, not real butter at all, she makes her consternation known. Waving a hand to rustle up some thunder, she prompts wild animals to roar and sends them leaping, while admonishing the nameless pitchman with the stern warning: “It’s not nice to fool Mother Nature!”

In more recent decades, of course, as mountains of now irrefutable scientific evidence have ominously shown, humans have been destructively assaulting nature, never mind fooling it, although, as in countries where politician-potentates have built huge dams to alter the flows of whole rivers, some have certainly tried fooling around with the rhythms and structures of the natural world.

Global patterns of climate change and the ever more rapid heating-up of the Earth’s atmosphere are very real, very dangerous trends. In recent years, they have been linked to everything from forest fires spreading out to destroy vast territories and famine-provoking droughts to the melting of polar ice sheets and unusually long periods of heavy rain or devastating storms. Having been abused, not just fooled, nature has expressed its wrath.

“Who has seen the wind?” Yoko Ono sang in a near whisper in a song of the same name that appeared on the B side of John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band’s “Instant Karma!” single in 1970. Its lyrics included these lines: “Who has seen the wind? / Neither you nor I. / But when the trees bow down their heads, the wind is passing by.” Ono’s song, gentle in its tone and message, and in the imagery it evokes, accomplishes in sound and verse what so many visual artists, moved by nature’s abiding and unstoppable, and discernible but sometimes invisible forces have long sought to achieve — to capture their impressions of them and create lasting records of the ineffable.

From the English painter John Constable’s precise, exuberant examinations of cloud formations of the early 1820s (he referred to the making of these pictures as “skying”) to the modern American painter Jane Wilson’s expressionist landscapes, in which skies of finely tuned color dominate many a large composition, many artists have been intrigued by the unending pageant and drama that are constantly unfolding above our heads and, more broadly, all around us, too, in the form of ever-changing weather patterns.

It was the Victorian-era art critic, philosopher, artist, and all-around idea man John Ruskin who, in his early, influential work Modern Painters (1843-60), argued that artists were obliged to remain true to nature. He also pointed out that nature can serve as both a starting point for art-making and the development of aesthetic ideas and as a kind of last-resort refuge or inspiration-providing mother lode whose inherent, internal logic or order is always right, offering fixed points of reference for creative impulses, the intellect, and the spirit. Nature, Ruskin believed, would never let an artist down.

This month, with spring arriving, we’ve dared to take a break from the dreary news of the world and to steal a moment in which to fashion some daisy chains, feed the birds, plant some seeds for a small flower or vegetable garden, skip stones across a pond, or just sit outside and soak up the sunshine. We’ve also reached out to a diverse group of artists who have long had nature and its forces on their minds when developing their ideas and creating their work.

In various articles that will appear in this month’s brutjournal, look for photographs by Bill Westmoreland, the magazine’s visual director, which he shot in rural, northeastern Pennsylvania. Who has seen the wind? The subjects of Bill’s photos have at least felt it, to be sure: old houses that were crushed by falling trees that had been struck by lightning or toppled in strong storms. In such subjects and their surroundings, over time, Bill has continued observing the effects of certain natural forces. Regarding some of the sites he has photographed, he noted, “I have witnessed the growth of specific trees over a 30-year period. I’ve watched them change the configuration of a field or pasture and alter horizon lines or the appearance of a landscape.”

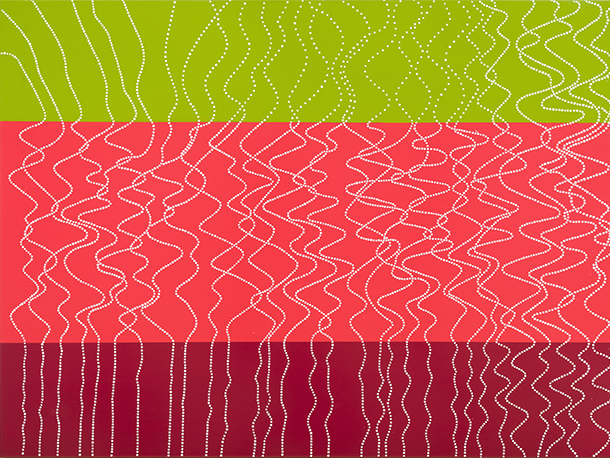

Bill’s images illustrate the text you’re reading now, as does a painting, below, by the artist Alma Realm, with its bold colors and broad, decisive brush strokes. Realm lives and works in northern Minnesota, where she is tapped into the rhythms of the land and the weather, and from where she sent us a succinct note regarding this month’s open-for-consideration theme. “The force of nature that gathers most of my attention is the imagination itself and all of its workings,” she advised.

This month’s issue also examines the New Jersey-based photographer Joel Simpson’s images in black and white and sometimes in color of natural rock formations or other geological or weather-fashioned structures whose shapes or patterns bring to mind modern sculpture or otherworldly phenomena — set pieces in dreamscapes that are, in fact, very much parts of our real, physical world. Our article about Joel’s work is pegged to the release this month of the third edition of a compilation in book form of his striking photographs.

We examine, too, the abstract paintings of the Australian-born, New York-based acupuncturist Ann Cecil-Sterman, who is also a well-known specialist in an ancient Chinese healing method that yields deep, multilayered readings of the human pulse. In her art, Ann has attempted to give visible expression to the qualitative and quantitative data she has gathered from some of her patients’ pulse readings. The forces of nature she explores and tries to represent in her art literally course through all of us but are normally overlooked.

Also in New York, we take a look at the offerings of Olfactory Art Keller, a small gallery founded by Andreas Keller, which specializes in the presentation of works of art that actively refer to, employ, or provoke their viewers’ sense of smell. Among the artists whose unusual — and unusually aromatic — works the gallery represents: Luiza Gottschalk and Gayil Nalls.

Meanwhile, in Chicago, we check in with Tiphanie Babinet, a young art dealer whose Hana Pietri Gallery represents the estate of Maurice Sullins (1910-1995), a self-taught artist who only started making paintings when he was 60 years old. Sullins went on to produce a large quantity of boldly colored oil-on-canvas paintings whose compositions are dynamic and inventive, combining wildly abstract passages with more conventionally representational subject matter. In his paintings, Sullins used vast expanses of sky as theatrical spaces in which clouds become bands of potent color, and animals seem to roam as freely as they would on the ground.

In an interview, Babinet told brutjournal that she is interested in the ways in which Sullins was able “to evoke nature and capture the essence of the natural environments he created.” She believes that, for Sullins, “painting allowed him to make sense of the world and to understand his place in it.”

Of course, that idea goes a long way toward explaining so many artists’ deep, abiding interest in nature and its daunting and sometimes enchanting forces, as varied, ageless, and ubiquitous as they are — and probably always will be, if we humans can just find ways in which to live with and respect them.

And that’s the truth.

No foolin’.