HERE’S A BRIEF PRIMER: ART BRUT, OUTSIDER ART, SELF-TAUGHT ART, “INSIDE,” AND “OUTSIDE”

Edward M. Gómez, brutjournal’s founder and editor in chief, is an internationally known specialist in the related fields of art brut and outsider art. A former senior editor of the magazine Raw Vision and a member of the advisory council of the Collection de l’Art Brut, the museum in Lausanne, Switzerland, that is the world’s leading research institution in its specialized field, Gómez has written extensively about art brut and outsider artists and their unique creations.

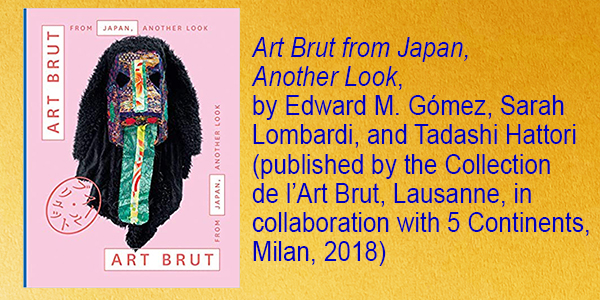

In 2018, he curated an exhibition of contemporary art brut from Japan for the Swiss museum (see “Resources,” below). For many years, he has led research and reporting efforts by non-Japanese researchers with regard to the still-developing Japanese scene; with close ties, since his childhood in Switzerland, to that country, his work has focused, too, on such Swiss art brut masters as Adolf Wölfli and Hans Krüsi, as well as other European art brut creators.

In his reporting and critical writing for Raw Vision, Hyperallergic, the New York Times, and other publications, including, now, brutjournal, Gómez has tried to broaden the discussion of art brut and outsider art beyond its traditional — and often expected — emphasis on artists’ biographies. He is interested in bringing the discussion of the work and ideas of the most remarkable art-making autodidacts into a more expansive critical and art-historical discussion in relation to modern art, contemporary art, and other art forms.

by Edward M. Gómez

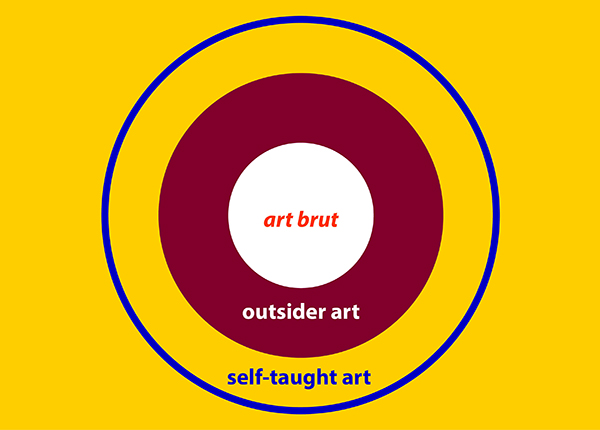

Some brutjournal readers might already be familiar with the history and evolution of art brut, outsider art, and so-called self-taught art, and also with some of the ongoing debates and developments in these related, overlapping areas. In any case, what follows is a brief summary of some of the main historical developments in what is often referred to generally, with a nod to all of these labeled categories, as “outsider art.”

First, it’s worth keeping in mind that “art brut,” “outsider art,” and “self-taught art” are category labels that collectors, researchers, and/or art dealers have come up with and used over time to identify certain kinds of artworks. These labels do not refer to artistic styles or movements. Let’s start by looking at the emergence, in Europe, of what came to be know as “art brut,” a history that is related to but not necessarily dependent on the development of psychiatry, especially as this medical field evolved during the late 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century.

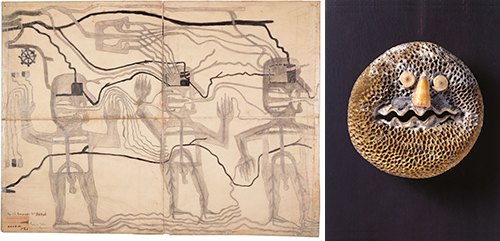

By the early 1900s, doctors at some psychiatric hospitals in Europe — at what used to be called “mental asylums” — had been paying close attention to the art-making activities of certain patients in such institutions. Their creations might have been drawings, paintings, pictures that incorporated real or imaginary writing, or handcrafted objects made with found materials. (Nowadays, some psychiatric hospitals have their own, in-house art-therapy or occupational-therapy programs for their patients.)

advertisement

Often, the mental illnesses with which the patients in such institutions were diagnosed were psychoses, especially schizophrenia. Psychiatrists in an earlier era did not have the more nuanced understanding of mental illness their successors in the late 20th century would acquire or that psychiatrists today possess and by which they are guided in their diagnosis and treatment of the mentally ill. Also, keep in mind that a wide range of drugs for treating mental illnesses was not available many decades ago.

In time, the artistic creations of patients in psychiatric hospitals came to be referred to as “psychotic art.” That was and remains a misnomer, of course, for it wasn’t that such art was psychotic per se, but rather that the people who created it had been so diagnosed.

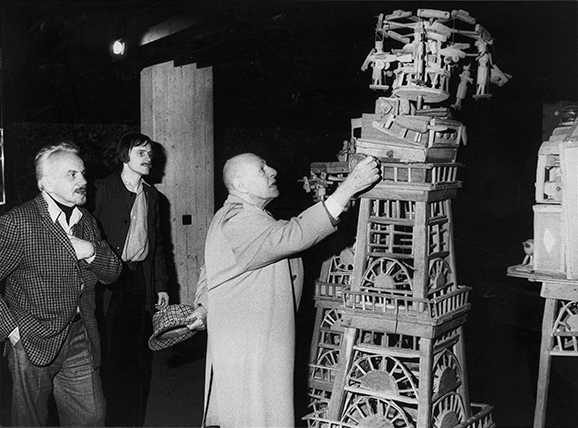

Fast-forward to the 1940s. In France, the modern artist Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985) and a group of his artist and writer pals, including André Breton, the leader of the Surrealists, became very interested in the work of such mentally ill persons — and, more broadly, too, in the artistic creations of inmates in prisons, or other unschooled makers of what they considered to be unusual, exceptional, hard-to-classify works of art. Common among such self-taught artists was the fact that they had not studied art-making techniques or art history in school.

Instead, they usually found themselves on the margins of mainstream culture and society, either by choice or by the force of circumstances. Often they used found materials to create their works. What’s interesting is that Dubuffet and his colleagues recognized such self-taught art-makers’ creations as works of art at all. In addition, they regarded such creations as unique unto themselves. They recognized that they did not fit into any existing, familiar art categories.

In formulating a description of such artworks, which came to serve as a definition of a genre Dubuffet dubbed “art brut” (meaning “raw art” in French), the inquisitive modern artist emphasized that not only was each individual piece unique unto itself — meaning that it could not be easily classified according to familiar genre or category labels — but also that each art brut creator’s more complete body of art was similarly unclassifiable.

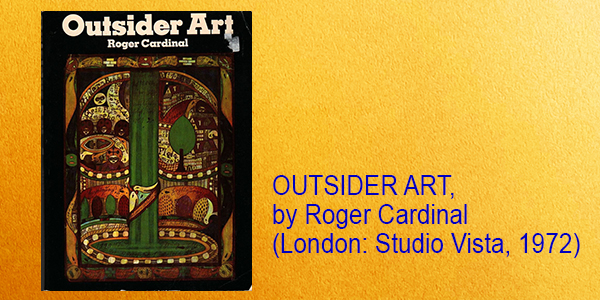

Fast-forward again to the year 1972, when, in Britain, the art historian Roger Cardinal’s book Outsider Art was published. As Cardinal, who passed away in 2019, told me on numerous occasions, when the editor of his book urged him to assign it a title that would clearly describe its unusual subject matter, he chose the term “outsider art,“ for both he and his editor felt that the French term “art brut” would be too difficult to translate effectively into English.

They also feared that its literal translation would not have made much sense to English-speaking readers or shoppers browsing in bookstores. In time, in the English-speaking world, the term “outsider art,” used as a substitute for and to sum up and reflect Dubuffet’s description of a certain unusual kind of art, stuck.

However, it also suggested a somewhat more expansive meaning.

Fast-forward again. In recent decades, primarily in the United States, the term “self-taught art” has come into use in the art market and the media to refer in an even more general, more open-ended way to the work of art brut and outsider artists. As a result, many creations produced by persons who can be called or who call themselves “self-taught” have emerged on the market — but can all such works properly be labeled “outsider art” or “art brut,” too?

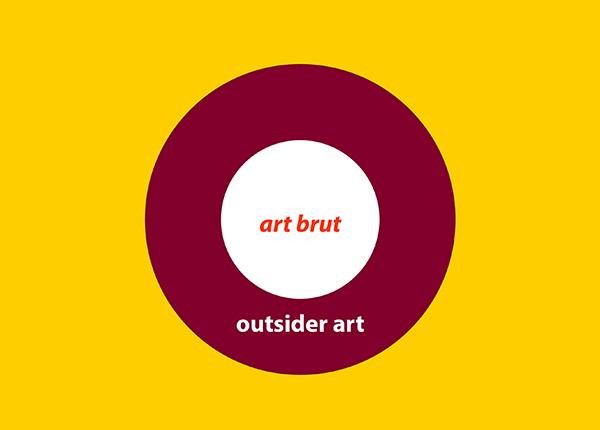

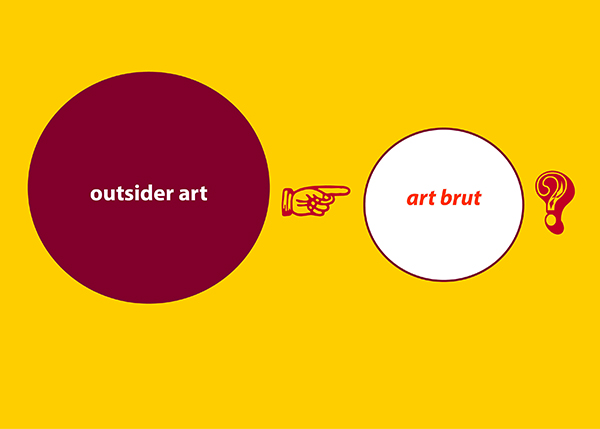

Technically speaking, all works of art brut can properly be placed under the broader umbrella of outsider art, but can — or should — all outsider artworks be regarded as art brut? Conversely, from the even broader vantage point of so-called self-taught art (and note that it is not the art that is self-taught; that word properly describes the people who make it), all art brut or outsider artworks are, by definition, produced by self-taught artists, but not all specimens of “self-taught art” can properly be classified as works or art brut or outsider art.

Generally speaking, to label a particular artwork or body of work “art brut” is to be guided by and to stick closely to Dubuffet’s guidelines about what constitutes this genre of artistic expression. They include an emphasis on an art-maker’s distance or even alienation, for whatever reasons, from mainstream culture and society, and also an emphasis on the uniqueness of what such an autodidact creates. In the strictest sense, “art brut” implies that an unschooled artist’s creations are expressions of a deeply personal vision and culture that he or she has devised. The Swiss art brut creator Adolf Wölfli’s most singular body of work and the ideas that shaped it offer a fine example of the meaning of Dubuffet’s label.

By contrast, art-makers whose creations have been labeled “outsider art” often may be seen to have had stronger, closer, more active ties to mainstream society or its institutions, such as organized religions or well-established folk traditions. Consider the lives and bodies of work of such American outsider artists as Howard Finster, Sister Gertrude Morgan, or Thornton Dial, Sr., for example, all of whom were deeply rooted in the religious and social traditions of the places in which they lived and produced their art.

“Self-taught” is the broadest in meaning of all of the three terms under consideration here. It may be used to refer to the artistic productions of just about anyone who has not been academically or otherwise trained to make art and it encompasses none of Dubuffet’s concerns about an art-maker’s status with regard to mainstream society or culture, or with regard to the uniqueness of whatever he or she might create.

Thus, almost all folk artists are self-taught artists, but, generally speaking, not all folk artists are outsider artists and they certainly cannot be regarded as art brut creators, for, as Dubuffet emphasized, the productions of genuine art brut makers are unique unto themselves. Folk art forms, on the other hand, are familiar and have been well-established for generations; rather than from any kind of uniqueness, it is from their commonness and recognizability that they derive their meaning and value. Folk art forms might be interpreted differently and revised by individual folk artists from generation to generation or from place to place within the regions in which such art forms are traditionally rooted, but folk art, by definition, has well-established, familiar formal and thematic starting points.

By contrast, the makers of true works of art brut and outsider art effectively create their own traditions. They might refer to or be somewhat inspired by traditional uses of materials or themes or stylistic aspects of certain folk art forms that are familiar to them but, ultimately, whatever their source materials or thematic starting points might be, what they produce is unique unto itself.

Thus, it was incorrect — and misleading — for certain institutions in the U.S. to have referred in the recent past to outsider art as “contemporary folk art” or to have shown the works of such artists as Henry Darger or Thornton Dial, Sr. under such a rubric.

“Art brut,” “outsider art,” “self-taught art” — these different terms really should be not be used synonymously or interchangeably. Each one has a specific, nuanced meaning, but as noted above, for the sake of convenience, “outsider art” tends to be used to collectively designate all of the related categories to which these different terms refer.

Having said all that, here are a couple of trends that have been gaining traction or debates that have been simmering in the outsider art field in recent years.

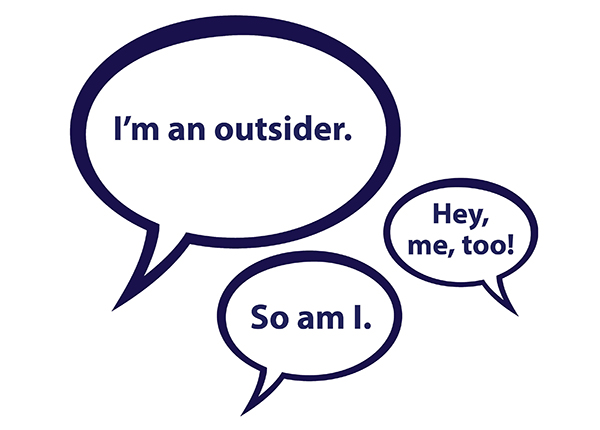

First, there has been criticism of the term “outsider” from those who believe it sounds pejorative or derogatory, and that it implies that whoever or whatever might be regarded as being situated on the “outside” — outside the supposed mainstream — has been so categorized or placed there by those who occupy positions on a privileged “inside.” Normally that “inside” is assumed to refer to places or positions within the mainstream art establishment and its supporting institutions and infrastructure.

Conversely, another trend that has been discernible in recent years has been the enthusiastic embrace of the “outsider” label by art-makers (and others) who might not be self-taught at all; in fact, they might be well-schooled and aware of art history and the art mainstream, and even well connected to it. Still, for some of them, adopting the “outsider” label, perhaps with a nod to cultural politics or to gaining another notch of hipster status, becomes almost a declaration of a kind of social-cultural-political position (and often, a stylistic position, too). Dilemma: If anyone can be a self-declared outsider, then who or what is a genuine outsider?

Finally, a critical observation regarding the creations of the most original and most distinctive art brut, outsider, and self-taught artists: To assume, never mind to state, that outsider art is somehow validated or legitimized by its real or imagined proximity to mainstream art product and/or its supporting institutions is to misunderstand the essential nature of outsider art.

This kind of art is, by definition, unique unto itself. Certainly, as with any other art form or genre, it may be compared to and contrasted with countless other forms of artistic expression but it does not need to be validated by anything — or anyone — other than itself. Like the best forms of artistic expression of any kind, in any discipline, outsider art embodies and communicates its own inherent truths.

The outsider art field has always been driven by research and collecting marching forward hand in hand. This was true during the pioneering era of Dubuffet’s research and collecting almost 80 years ago. It’s still true today, even if or when that research is led by primarily commercial agents — art dealers. In fact, some of the most significant contributors to this field have been art dealers who have also been active researchers and collectors in their own right. Their enthusiasm and passion are as palpable as they are enticing every time one sets foot in their galleries or encounters their displays at an art fair.

Although art brut and outsider art’s historical roots lie in Western Europe and North America, where these related research-and-collecting fields originally evolved, today research about and the collecting of this kind of art are advancing in such places as Japan, India, Iran, and parts of Africa. Many regions of the world that lie beyond art brut and outsider art’s roots territories are waiting to be explored, not only by foreign researchers but also by their own local art historians, researchers, collectors, and art dealers. Every year brings more discoveries of hitherto unknown or unrecognized art brut and outsider artists’ achievements — and new opportunities to quibble about how best or most accurately to label them.

Resources

A section of the website of the Outsider Art Fair titled “The Field” offers an informative introduction to the some of the main aesthetic ideas, historical events, and artists’ works that have informed the outsider art phenomenon. You can find it here.

The catalog of the exhibition Art Brut from Japan: Another Look, which Edward M. Gómez curated, and which was presented at the Collection de l’Art Brut, in Lausanne, Switzerland, from November 30, 2018 through April 28, 2019, was published in a bilingual, French-and-English edition. It can be purchased from Amazon.com, here.

In the United Kingdom, it can be purchased from Waterstones, here.