GETTING TO KNOW THE CAREER OF SEYMOUR ROSEN (1935-2006)

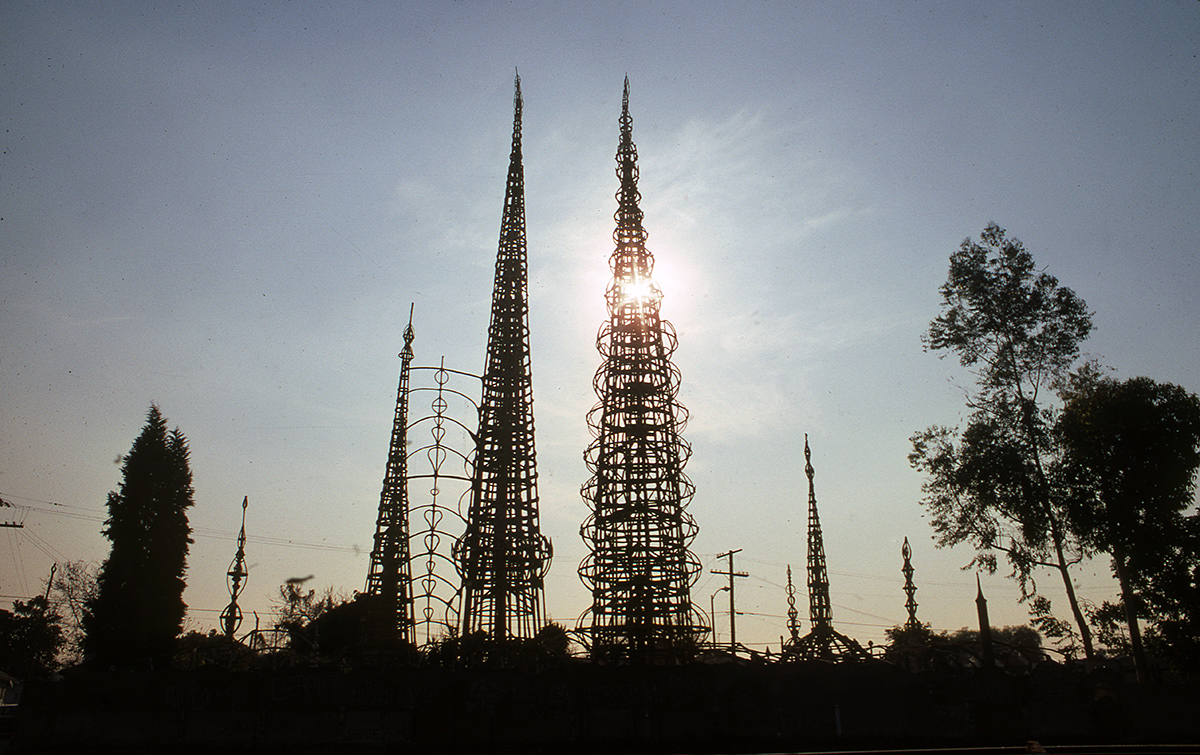

In the early 1950s, the California-based photographer Seymour Rosen began documenting on film the Italian immigrant Sabato (“Simon”) Rodia’s Watts Towers in Los Angeles. Deeply interested in such site-specific art environments made by self-taught artist-designers, Rosen went on to establish SPACES–Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments, a nonprofit organization whose full name vividly expressed the nature of its mission.

By the time Rosen died in 2006, SPACES held tens of thousands of photographs, video and audio tapes, and other materials documenting hundreds of artist-produced environments. In 2017, the Kohler Foundation, which is located in Kohler, Wisconsin, and has close ties to the nearby John Michael Kohler Arts Center, in Sheboygan, took on SPACES Archives as a preservation project.

Working there today, Annalise Flynn is a member of a team of specialists tasked with preserving the vast array of materials amassed by Rosen and his successor, Jo Farb Hernández, who has since moved on from that position. (Now recognized as the SPACES director and chief curator emerita, Hernández will be contributing articles to brutjournal based on her own research about artist-made environments. See her article in this sample issue of brutjournal about Salaguti’s site-specific environment in Spain.)

Now, dipping into some of the SPACES Archives’ trove, Flynn offers brutjournal readers a summary of Rosen’s career as an observer and documenter of the self-taught artists’ ambitious, environmental creations he so passionately championed.

by Annalise Flynn

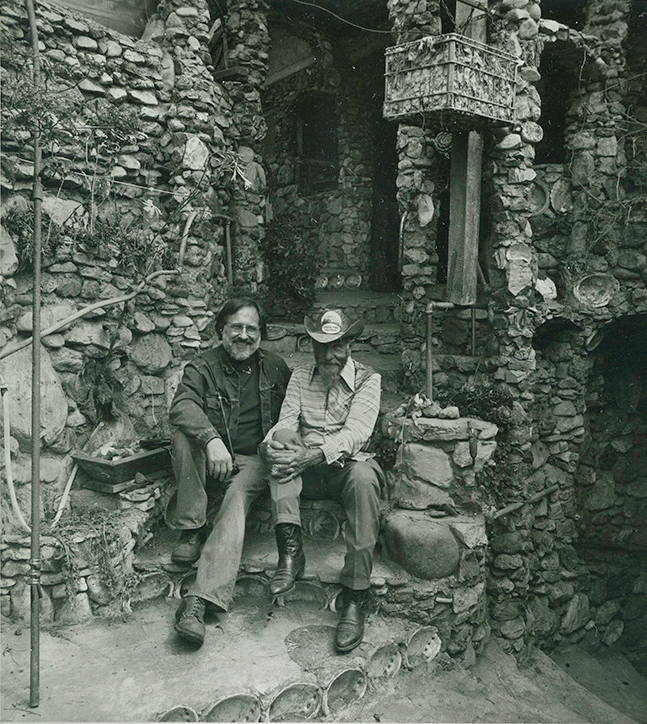

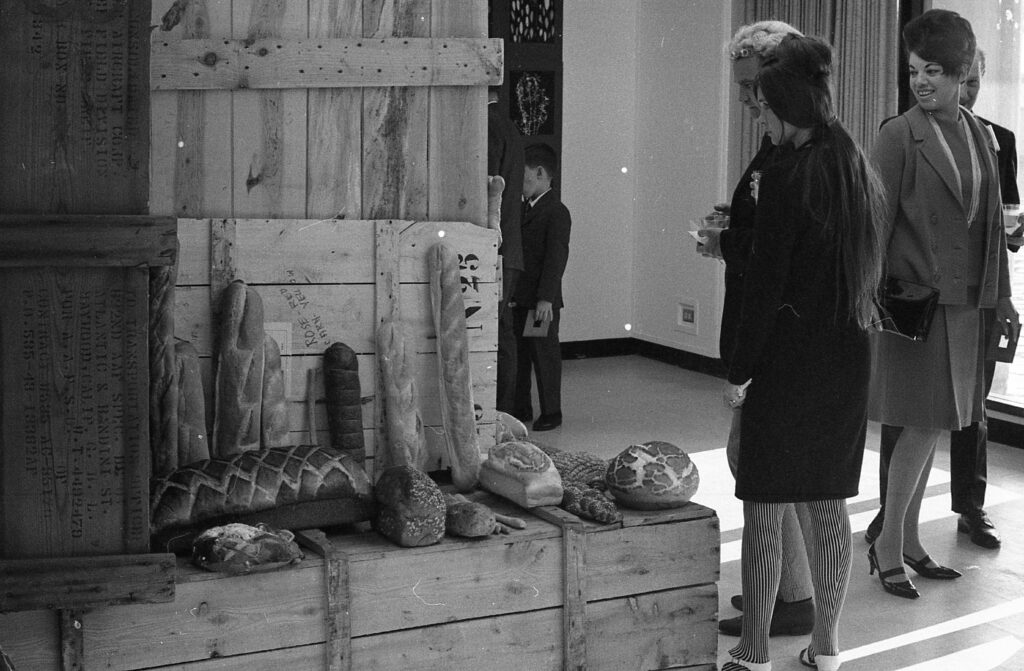

Soon after his death in 2006, little baggies of Seymour Rosen’s ashes began appearing unceremoniously at the homes of his friends and colleagues. These packets of “cremains” were accompanied by brief instructions and funding for specific activities their recipients were asked to carry out — including spreading them on location at the Harrods Food Hall, in London, throughout a particular garden, at a tango event, and at a bakery in Paris. Naturally, Rosen also listed among the everyday places where he wanted his remains to be deposited several art environments — a number of homes, gardens, and studios that various artists had fully transformed into site- and life-specific works of art. Over the course of his career, Rosen had helped define and make visible this genre of art-making through his work as a photographer, curator, and arts advocate.

In his last will and testament, Rosen cited five artists’ environments at which he wanted his remains to be deposited. They included Fred Smith’s Wisconsin Concrete Park, in Phillips, Wisconsin; Nitt Witt Ridge, a house in a coastal town in southern California; John Medica’s garden, in Santa Rosa, California; Leonard Knight’s Salvation Mountain; and an unspecified “important environment” in France. (How or why he limited himself to only these sites of the hundreds known to him is anyone’s guess.) Rosen’s well-defined, all-encompassing belief in the value of cultural and creative phenomena as ordinary as a personal garden or as extraordinary as a three-story, rainbow-hued adobe installation like Knight’s in the middle of the California desert is perfectly summed up by this list of final resting places for his own remains. Its message: that its author wanted to be a part of it all. Apparently, Rosen approached death just as he had pursued his life — dedicated, as he wrote in the catalog of his 1966 exhibition-cum-personal manifesto I Am Alive, to the “various methods by which man says, ‘I exist […]. I am alive.’”

Nowhere was this sentiment better exemplified than through the work of SPACES–Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments, a nonprofit organization he founded in 1978. He established it because he had felt frustrated by the fact that many of the art environments he had encountered, which frequently had been created out of vulnerable materials by marginalized artists, either would or could not be preserved. SPACES’ mission: to identify, document, and advocate for the preservation of such unique, fragile art environments.

In the introduction to his book In Celebration of Ourselves, which was published in 1979, Rosen noted, “I began to get frantic when I’d see something great and go back a year later and find a parking lot there, or just nothing. Everyone seems to take it for granted or else they don’t care; they think it’s junk [or that it] has no value because it’s not ‘art.’” Today, SPACES Archives holds Rosen’s entire photographic oeuvre, featuring his documentation of more than 100 art environments, many of which no longer exist in their entirety or at all.

In Celebration of Ourselves contains Rosen’s remarks about the art environments and other “wonders” he photographed. In the book, he wrote, “They defy categorization, and that fact has resulted in an ongoing battle to get institutions to recognize the value of documenting and preserving these forms of expression. Collecting the material has been, of necessity, a labor of love […]. But I am told that perhaps the time has come; perhaps a varied and complete record of the most ephemeral events of the American spirit and heritage can finally be assembled for us all to share. Maybe we will even be able to preserve the environments and objects so that people can see them firsthand […] to acknowledge the magic made available to us by those whose work looks best outside of institutional walls — with the hope that we all will take the time to do our own explorations.”

Rosen’s “labor of love” has resulted in the world’s largest repository of archival documents related to art environments, a genre that includes steel towers, bottle buildings, shell houses, doll villages, hand-carved caves, and many more intimately crafted worlds.

Rosen tirelessly campaigned on behalf of the preservation of such site-specific artworks; his communications with colleagues and other interested parties around the United States and overseas, which is represented by a large collection in the SPACES Archives of his cajoling correspondence, helped give rise to a community of fellow advocates. Many of them continue to submit photos, writings, and site news to SPACES Archives today, 15 years after Rosen’s death.

The archives, which contain documentation of more than 1400 environments, are housed in Kohler, Wisconsin, where they constitute a preservation project of the Kohler Foundation, a nonprofit organization that supports broad public access to the arts and education. Much of this material is shared freely with the public on the SPACES Archives website (www.spacesarchives.org).

In the first SPACES newsletter, which was issued in 1982, Rosen, referring to the large-scale art environments he so admired, wrote, “There is something out there.”

Now, to honor his legacy, it is up to us to continue looking for — and documenting and preserving — all of it.

Annalise Flynn is an art historian, writer, and arts administrator based in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. She can be reached at vernacularartservices@gmail.com.

brutjournal is deeply grateful to SPACES Archives for generously allowing the magazine to publish photos from its collection.