ONLINE SHOP ÉTAGÈRE FOUNDER ISABELLE JUSSEAUME BRINGS A CONTEMPORARY EYE TO UNUSUAL TREASURES OLD AND NEW

by Sarah Fensom

For many years, Isabelle Jusseaume, 36, has collected a variety of idiosyncratic art objects, but when she launched her online shop Étagère in December 2020, she felt justified about the obsessive searching for, gathering, and sharing of unique pieces of folk art and handcrafted, artisanally made works in which she had long indulged. As a young, Internet-era entrepreneur for whom hanging out her shingle in cyberspace came naturally, to offer a large selection of the unusual objects that had long fascinated her, she inaugurated Étagère as both a website and an Instagram account (@etagere_nyc). Her curated boutique opened with a selection of roughly 20 objects she had found in France prior to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2020.

Jusseaume, who is French, was born in Limoges, a city in southwest-central France that is known as a major producer of porcelain, but she has lived more than a decade in New York and operates her online shop out of her home in Brooklyn. Her mother, a pharmacist, collected antique pharmacy bottles and related accouterments, while her grandmother worked in an antique shop that became an after-school hangout for young Isabelle and her cousins.

Even as Isabelle developed her own interest in unconventional, more modern and design-conscious artisanal creations, in a recent interview, she recalled that, over the years, a collection of “heavy 19th-century furniture” that was “very old France” found its way into her family’s home, so her aesthetic sensibility has been informed by firsthand exposure to a range of styles and materials

After decamping for Paris when she was 18, Jusseaume took art-history and museum-studies courses at several universities and became drawn to outsider art, folk art, and works that felt unique to her. She wrote a thesis on the intersection of music and performance within No Wave, the avant-garde music and visual-art scene that emerged in New York in the 1970s, and later moved from Paris to New York, where she became involved in the robust DIY music scene that defined North Brooklyn from the late 2000s through the early 2010s.

About her approach to curating Étagère’s offerings, Jusseaume explained, “I mainly collect things that are handmade and not recently. I don’t sell particularly expensive things; I want my friends, who are mostly artists, to be able to afford what Étagère has to offer.”

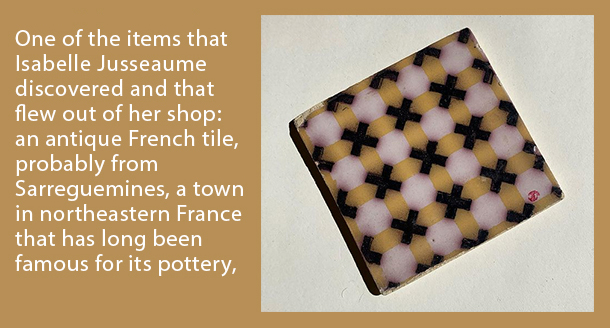

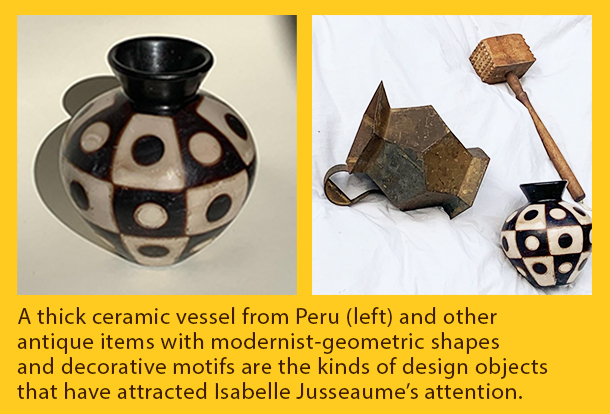

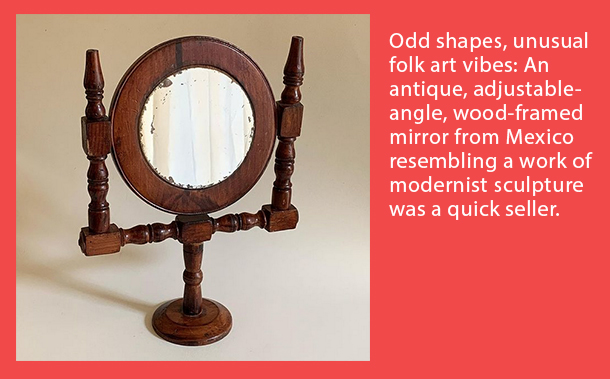

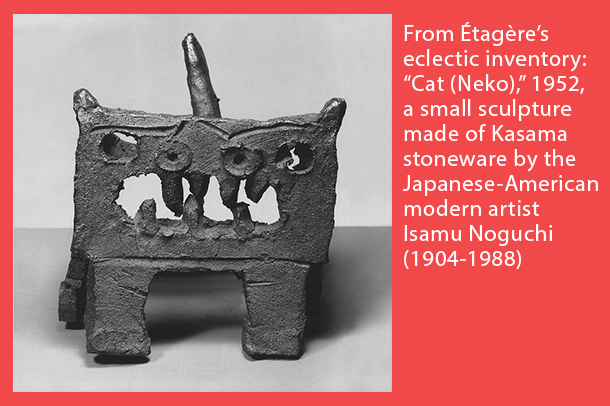

The shop’s followers have come to recognize it as a venue that presents a limited, rotating stock of time-worn, often quirky, or even humorous objects, as well as unusual modernist gems. Among the items Jusseaume has handled: a rustic Serbian wooden distaff (a staff for holding the flax or wool in spinning); a southeast-European ceramic bowl with a fat spiral hand painted in its center; a weathered, papier-maché Mardi Gras mask; an elegant, silver-plated “frog” candle holder from Italy; a very flat, red-painted and patterned, double-sided wooden hair comb from India; an antique French ceramic tile whose motif resembles a contemporary minimalist painting; and a boxy, cat-shaped sculpture made of fired clay by the Japanese-American modern artist Isamu Noguchi in 1952.

Earlier this year, Jusseaume traveled to Mexico City with Sophie Lou Jacobsen, a product designer known for her creative work with glass, and Ioana Hercberg, the chef and owner of La Cantine, a popular cafe in Brooklyn’s Bushwick district. About her research-and-buying journey to Mexico, Jusseaume said, “I was expecting to find ceramics from Oaxaca, particularly with a type of drip glazing that’s popular in that region, but I was also looking for redware pottery, newer artisanal products, and textiles.”

In Mexico City, Jusseaume sought out some of that vast metropolis’s well-known flea markets, where she found such items as a drip-glaze, fern-green ceramic serving dish in the shape of a teardrop with a low foot, a thick handle, and a chunky, crimped rim. Although it looks like it could be an antique, this dish is actually a contemporary piece that most likely was made in the Pantamban region of Michoacán, a state in western Mexico, whose western border is the Pacific Ocean.

Jusseaume also came across a white Oaxacan bowl with a traditional drip glaze. Made in the 1930s, it features broad, black line work in its interior and a series of dazzling yellow, orange, and green amorphous shapes. Its rich hues are indicative of its age. Jusseaume observed, “To make these vivid colors, the artisans needed lead paint, so this is definitely a purely decorative object now.”

In Mexico City, Jusseaume stayed in San Miguel Chapultepec, a colonia in the southwest-central part of the capital. She visited Casa Ahorita, a shop dedicated to Mexican folk crafts that is operated by the writer and curator Su Wu, and Luis Barragán’s Casa Prieto López (also known as the “Casa Pedregal”). Barragán, the foremost figure in the history of modern architecture in Mexico, designed the home in the Jardines del Pedregal development in the late 1940s, and it’s still a functional residence today.

So far, Instagram has allowed Jusseaume to easily connect with customers and share her creative collector’s vision with them. Now, as Étagère grows, Jusseaume is planning to produce some design objects of her own, working with artisans to promote and sell their collaborative creations. In April of this year, she debuted plates and bowls made by artists in Horezu, a town in south-central Romania that is a center of traditional folk ceramics. Each of the slip-glaze, terracotta dishes they produced was handmade and unique.

The colors of these dishes — rich brown, orange-red, green, and blue hues — result primarily from the chemical properties of the clay from the Horezu region that is used to make them. Decorative patterns on these items feature concentric circles, wavy lines, flowers, and wheat ears that are applied with goose quills and drawn through with fine sticks in a traditional technique called “jiravirea.”

Jusseaume told me that she is aware of the belief some people hold that “art is necessarily bourgeois,” and that, to counteract it, through her design-focused shop, she aims to offer unique everyday objects that are both accessible and beautiful. Referring to the phrase “bread and roses,” a slogan of the early-20th-century women’s suffrage movement in the United States, which inspired a well-known poem written by James Oppenheim in 1911, Jusseaume said, “Basically, it’s the idea that we don’t just need necessities; we need beauty, too.”