THE WILD BIRD WOMAN, HER WILD BIRDHOUSE, AND THE FROG SWAMP

In London, brutjournal’s artist-correspondent Cathy Ward recently caught up with the artist Judith McNicol, who, like Cathy, has long been interested in the work and ideas of the late Swedish-born painter and feminist activist Monica Sjöö (1938-2005). Ward’s separate article about a rare exhibition of Sjöö’s paintings that is now on view at Beaconsfield, in London, also appears in this issue; click here to see it.

Now, here is Ward’s report about her visit to McNicol’s home and studio near London, where she reacquainted herself with the history of her friend’s art-making career and the thinking and personal experiences that have influenced it.

Cathy Ward reports:

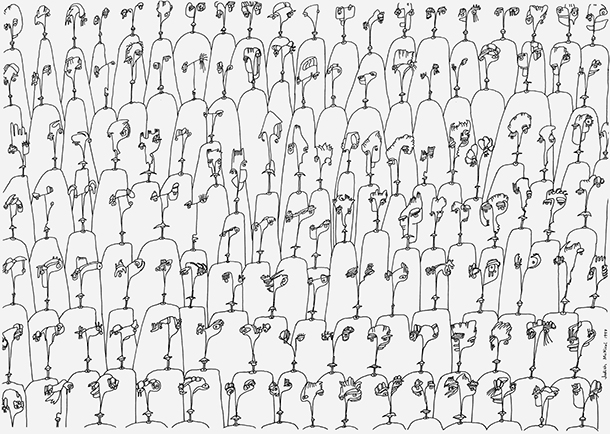

“Judith McNicol leads us to a country of wild dreams, where each form seems to give birth to another fantastic cycle of creation, a tumult of the creative process. Wherever the eye comes to rest, an adventure is played out before us, its apparent anonymity represented by a multitude of prolific symbols.

This strong, original work is clearly rooted in unknown territory, whose features the artist seeks to reveal to us. Her work is concerned not only with exploring but [also with] conquering this territory. It is this struggle that Judith McNicol wishes to share with us.”

Gérard Sendrey (1928-2022), founder of Création Franche, a museum in Bègles, France, in “An inner Journey into Unknown Territory” (English translation of “Les étrangères confidences de Judith McNicol”), published in Mapping The Inner Universe: Drawinks by Judith McNicol, 1994-2004 (Edinburgh: Bumblebee Press, 2005). This book is available from the Inkywings website, here.

In 2001, I met Judith McNicol by chance at Artesian Arts, a gallery in Edinburgh, Scotland, that was run as a collective by a group of artists whose wide-open welcome was democratic in spirit and who published Artesian, a quarterly magazine whose tag line stated, “Upwelling Art and Creativity, the Voice of Scotland’s Grassroots Arts.”

Judith was Artesian Arts’ founder. Along with a core group of fellow artists, the venue they established encouraged art-makers and other contributors to show their work there, expressing themselves with unrestricted freedom. An early participant in the gallery’s exhibition program was the Swedish-born artist, feminist, and eco-activist Monica Sjöö, who had been living in Bristol, in southwestern England, since the late 1950s.

Sjöö’s paintings were on view when I made that trip to the north to visit Artesian Arts for the first time. In conjunction with the presentation of her exhibition, Monica, who stayed with Judith and her partner, Fiona (who is now her wife), in their home during her sojourn in Edinburgh, wrote an article for Artesian (issue number 3, winter 2001-02).

In that piece, “The Artist as Reluctant Sharmanka,” whose title makes use of a Russian word meaning “barrel organ” or “hurdy-gurdy,” Sjöö observed about herself, “In struggling to speak for Mother Earth and her spirits, for Gaia’s laws of respect for everything that lives, and for witches and wise women of all ages and times[,] I am most certainly outside the patriarchal status quo, which believes that Earth is simply a human resource to be exploited by ‘mankind.’”

During its run of several years, Artesian Arts welcomed, offered encouragement to, and presented the creations of many different artists working in a range of media and genres.

In 2006, Judith McNicol moved from Edinburgh to Bushey, a commuter town on the northwestern border of London in the county of Hertfordshire, where, back in the 18th century, the notorious highwayman Richard (“Dick”) Turpin, a robber who stole from travelers, plied his predatory trade.

Recently, I visited Judith at her home in Bushey, where she escorted me through her garden. There, she has outfitted tree branches with fast-food feeding stations for birds, the ground serves as a small-scale housing estate for hedgehogs, and a large, swampy spawn pond provides a home for a burgeoning population of frogs. With her verdant garden, Judith has created a sanctuary for nature; at the far end of this lush space, she has made one for herself, which she calls “The Shed.” It’s an all-in-one personal refuge, laboratory, and artist’s studio.

In this special space, Judith has crafted many imaginary birds, along with custom-made environments — original birdhouse constructions — in which her fantastic avian menagerie resides. In The Shed, evidence of her handiwork is everywhere — electrical components, wire and miniature light bulbs, motors, lots of plastic things, hot-glue guns, and seashells, all in various states of being stuck together or taken apart and reassembled, like pieces of three-dimensional jigsaw puzzles.

Pointing to one of her works, “The Junk Birdhouse,” Judith said, “This one is a home for 19 birds that are all engaged in different activities in a little community. I was influenced by the [self-taught, Russian-born] artist Eduard Bersudsky. He and his wife, Tatyana Jakovskaya, founded the famous Sharmanka Kinetic Theatre in Glasgow, and Eduard’s mechanical sculptures always included birds. We became good friends, and if I had stayed in Edinburgh, I would have worked with him as his apprentice. I was very fond of Eduard and Tatyana. Lovely, lovely people.”

(The website of the Sharmanka Kinetic Theatre, which is run by the self-described “sculptor-mechanic” Bersudsky, Jakovskaya (director), and Sergey Jakovsky (sound designer), can be found here.)

Inside the “Bird Gallery,” which resembles a large-size dollhouse, each room is the domain of one or more of Judith’s mixed-media assemblages, with miniature black-and-white artworks depicting birds — of course — on their walls. She explained, “I was drawing buildings that were half-bird and half-building, which I loved. When I was about five or six years old, our neighbor upstairs made a doll’s house for me, and it had lights. I still have it. I learned about wiring then and I learned about [how it had been assembled]. Over the years, my mum and I added new floors, so it came naturally that [, later,] I should create a bird-building gallery to hold all these birds.”

Judith noted, “For me, birds symbolize the free spirit.”

I pointed to a vessel on a shelf, and, describing it, Judith said, “That ship is called ‘Bountiful Spirit’. Heralda is its helmswoman; as my spirit guide, she first appeared in my earliest drawinks in 1994, and she has been with me ever since. She has appeared not only in drawings, sculptures, assemblages, and my novel Olimnia’s Last Term (London: New Generation Publishing, 2020), but [also] almost in reality, for I had a visitation from her last autumn.”

Always curious about a visitation, I asked Judith to tell me more.

She recalled, “I was just feeling low and alone, sitting in an armchair, my arms crossed over my chest, with my eyes shut. After a few minutes, I saw Heralda sitting in the chair opposite. She carried a staff with a light at the end and pointed it and walked toward me. I said, ‘Hold on, I’m not ready.’ Once I felt ready, she pointed the lit staff toward and then into my heart, and I felt an electric shock throughout my body. A sudden surge of energy and then, wow, I was back to myself again. Heralda healed me in that moment.”

Judith McNicol trained as an earth scientist, and her passion was for roaming the planet, often to far-flung, uninhabited regions, on field studies to collect minerals and map the terrain. She was “seeking to understand how the physical world came to be the way it is”. However, she could only make such exciting treks to study distant lands during vacations or sabbaticals. Instead, for most of those 20 years, she was mostly confined to the halls of academia, where she felt trapped and confined.

In time, Judith developed myalgic encephalomyelitis, which is also known as “chronic fatigue syndrome” or “ME/CFS.” A long-lasting condition with which a wide range of associated symptoms, its most common feature is a feeling of extreme tiredness. In Judith’s case, her illness left her bedridden for long periods of time (mostly during her university’s regular semesters, not during vacation periods). In her confinement, she started using her geologist’s pens to draw freely, and what began emerging on paper felt to Judith like the wide-awake, visual manifestation of a dream.

She told me, “It was as if the images had accumulated over the years, just waiting for a moment when the left side of my brain would shut down, and the right brain could flourish.” In this way, Judith’s mapping of her private, inner universe, in which her bed became her traveler’s raft and her pen both its compass and rudder, began. She set sail, now into the world of a deeply personal kind of art. (Today, too, Judith is a highly experienced neurosomatic therapist.)

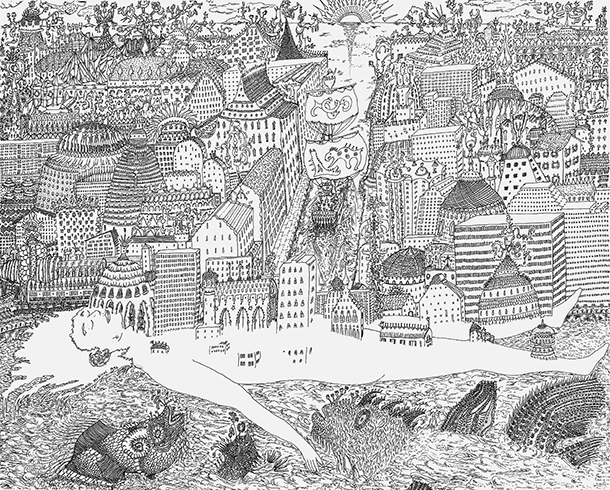

Judith recalled, “Amazingly, the first two or three pictures I drew — I call them ‘drawinks’ — symbolized my feeling of illness, powerlessness, and alienation. One of them is called ‘The Heavy City’ [1994, India ink on paper]; in it there’s a woman lying flat and naked, with a city weighing down on her, and not a soul to be seen. That’s how I felt about working at the university; it was soulless and deadly, and my whole spirit was crushed by trying to survive in that environment.”

I commented that, in that picture, I could see the city being absorbed by her body, too.

Judith replied, “I think that’s when Heralda first appeared: on a galleon, striking a pathway through to the horizon. She was saying, ‘Follow me, get on the ship. Follow me through the city, where we’ll head for the ocean and the distant horizon.’”

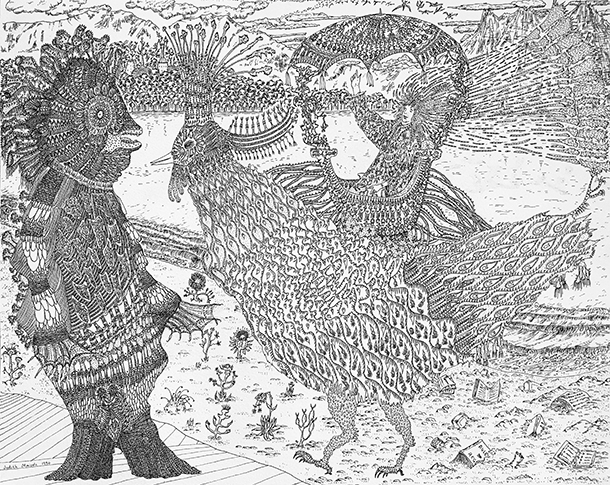

Judith also referred to “The Can’t Stop Now Chicken (or The Flight From Academia)” (1994, India ink on paper), another large “drawink” from around that same time.

About it, she observed, “In it, on the left, there’s a fish, and on right, there’s a chicken. The chicken is desperate to run off and do whatever she wants, taking me with her. On the left is the stranded fish, out of water. This [image reflects] the essence of why I was ill — I was in conflict between a part of me that wanted to be alive, creative, and in touch with my spirit, versus [a part that was like] a dying fish out of water, stifled and trapped by all these rules, regulations, timetables, and blah, blah, blah. Both of those characters struck me so strongly, because they epitomized and really encapsulated what I was going through.”

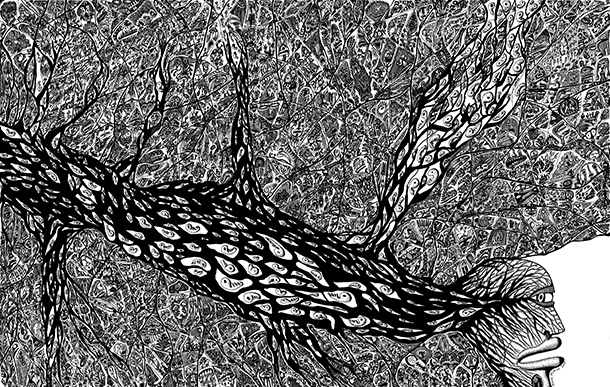

“The True Nature of Dark Matter” (India ink on paper, 2005), one of the largest, most intense later works of Judith’s that I’ve seen can only be described as a cross section of organic matter — as some kind of flayed, dissected creature. It’s extremely dense, and, in it, there is a lot going on. I asked the artist to tell me about it, and she said:

“I had an image of this before I started [making it]. I wanted to resolve the two parts of the self — that part that is in despair, and that which has to do with all the traumas and horrors of getting through life. On the other hand, embryos of hope will survive and find joy, peace, and contentment. There has been a lot of discussion about ‘dark matter’ in the universe. I thought, ‘We carry our own “dark matter” within us,’ so that’s why I called this work ‘The True Nature of Dark Matter.’ Despite all that, there is [still] the flow of hope; it’s coming into the brain, into being.”

About what I referred to, above, as a “dissected creature” in this image, Judith added, “It is really a huge web, with each cell containing ‘dark matter’ (i.e. despair), while the embryos contain hope. Only the woman portrayed can see the web, just as no one can ‘see’ dark matter in the universe, as the drawink is really a ‘map’ of her unconscious.”

Judith’s art-filled home and studio are something of another world of color, unexpectedly combined and juxtaposed found objects and materials, and the distinctive assemblages filled with energy and spirit the artist has conjured up.

I asked her about her more recent creations, and she said, “In 2021, I began working on ‘Journey of the Lost Souls,’ a three-part assemblage made from card stock to meet my need to create an image of the afterlife. Part one shows Heralda coming to collect the Lost Souls and bear them in her ship to the Golden City.”

“Part two [seen here, above] shows more than 30 Lost Souls heading up the hill to the Gates of the Golden City, where Heralda is waiting to welcome them. Part three, which is still in progress, will show their arrival in the Divine Realm beyond the Golden City. All of these assemblages light up, so the Lost Souls will not have to feel trapped in darkness.”

Judith added, “When I’d finished part two of this new work, I cried and cried as I realized that I was one of the Lost Souls waiting for Heralda to take me ‘home,’ and now that piece of work helps me feel safe and reassured, knowing that I won’t be alone.”

Through her prolific artistic production, Judith has fashioned a unique and dedicated way by which to respond to life’s difficulties and joys. Today, in her professional work outside her studio, in her role as a neurosomatic therapist, she helps others who are wrestling with chronic illness.

Having also written several books on the subject of how to live with and overcome such illnesses as CFS/ME and fibromyalgia, both in her art-making and in her therapeutic work, Judith has made a point — and an art — of always seeking and moving toward the light.