IN A NEW EXHIBITION, THE TOKYO-BASED, SCOTTISH ARTIST JACK McLEAN SYNTHESIZES THE REBELLIOUS SPIRIT AND UNEXPECTED IMAGERY HE HAS BEEN DEVELOPING FOR SEVERAL YEARS

Published on February 15, 2026

“Jack McLean: ‘A Thousand Rockers’ + ‘Edinburgh Burn-up’ and Other Stories”

JPS Gallery

Tobu 2nd Building, ground floor

6-27-4 Jingumae, Shibuya-ku

Tokyo 150-0001 Japan

Telephone: (81) 03-6812-9306

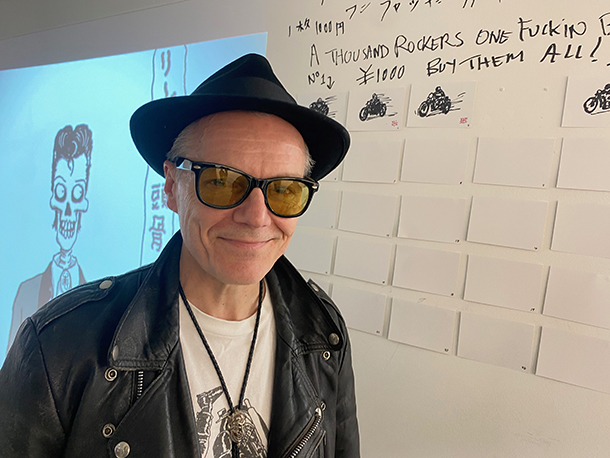

by Edward M. Gómez

TOKYO — Go to sleep, tired New York! Put a lid on it, ye olde, exhausted London. Take your last sip and then bonne nuit, dear preening Paris.

Memo to urban night owls: The action is over here in Tokyo a-go-go, a dynamic metropolis that already had both feet firmly placed on the terra incognita of the 21st century back when the early postmodernist rumblings of the 1980s prompted critics and creatives elsewhere to marvel at the pulse of Japan’s ancient-ultramodern capital. Japan was home to niche marketing, cross-branding, pop-up retail, conceptual and linguistic hyperlinking, and the flourishing of unique urban tribes and subcultures long before such trends and phenomena had names.

It’s against this fecund, social-cultural backdrop and in such a vibrant setting that the Scottish artist Jack McLean, who has lived and worked in Japan for more than 30 years, has developed his distinctive body of work. It has been inspired by certain popular subcultures even as, in a way that concretely expresses his deeply personal aesthetic sensibility, it seems to engender — and serve as the lodestar for — a whole new subculture of its own.

McLean’s art is now being featured in a solo exhibition, “Jack McLean: ‘A Thousand Rockers’ + ‘Edinburgh Burn-up’ and Other Stories,” at JPS Gallery, in Tokyo’s Harajuku district, where it will remain on view through February 28, 2026.

This mini-retrospective showcases a selection of McLean’s work in various formats from the past few years. For both newcomers to McLean’s art and viewers who have followed the development of his ideas and art-making methods during this recent period, this presentation not only serves up a generous selection of his paintings on canvas or paper, drawings on paper, and super-short animations based on his drawings, allowing them to be seen together in an exuberant, informative way.

This gallery show also offers McLean’s creations in assorted formats, some of which share similar subject matter, an opportunity to cross-pollinate and bounce their energy off each other. Gathered together like this, his varied works offer a strong sense of what, in effect, is a kind of subculture among subcultures, which McLean has conjured up over the years; it’s both an imagined community and a kind of worldview to whose spirit his art gives tangible form.

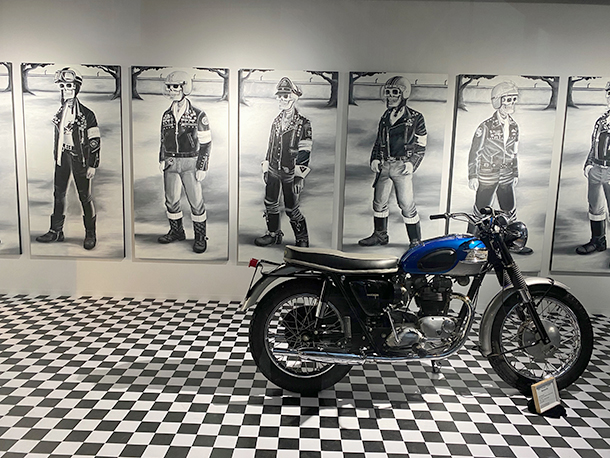

The artist’s subject matter vividly reflects the emblems and elements of his passionately imagined tribe: motorcycles, leather jackets, cool-guy vibes, rock’n’roll attitude (especially of a punk-flavored strain), and the enduring, mythical allure of the open road. Throw in a fondness for haunted-house imagery — skeletons and skulls and cross-bones, keeping in mind that the latter motif has long been associated with biker culture — and a sense of humor that is somewhere beyond offbeat.

(In biker culture, the skull and crossbones symbol refers to rebelliousness and, of course, mortality. Its biker-related origins date back to the post-World War II era, when veterans took up certain military emblems and employed them to express a sense of brotherhood and fearlessness in the face of conventional social attitudes.)

Sometimes McLean’s humor can feel so dry that it becomes absurd, which is, it often turns out, its point. In certain performance-art pieces, for example, he has turned up as a silent, brutally self-effacing clown, or he has appeared in the disguise of a leafy, green bush, aspiring to disappear into a bland, nondescript landscape.

brutjournal caught up with the artist on the occasion of the opening of his new exhibition in Tokyo. We started by asking him about his interest in motorcycles and biker culture, and, in particular, about how he came to fuse the spooky imagery of skulls and skeletons, a rocker vibe, and his interest in the powerful bikes that are sometimes referred to by their owners as “beasts.”

McLean said, “Like they are for many teenage boys, for me, motorbikes were part of a natural progression of interests that included rock’n’roll, alcohol, cigarettes, girls, some drugs, and other stuff. I was always into motorbikes. It’s an interest that has stayed with me my whole life. There’s nothing cooler!”

Jack’s forays into the world of cool started when, as a young boy, he listened closely when his mother played Jerry Lee Lewis and Eddie Cochran records, and then later, as a teenager, when the sounds and rebellious spirits of such bands as the Sex Pistols and the Clash seized his imagination.

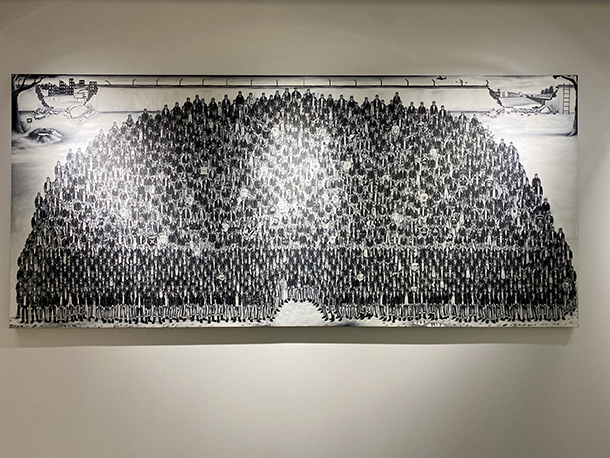

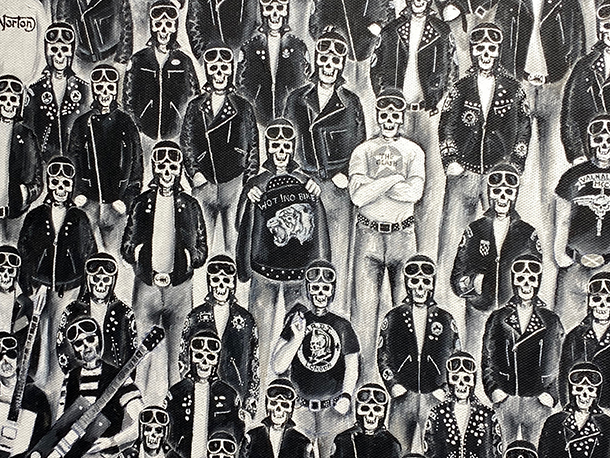

A centerpiece of the current Tokyo exhibition is McLean’s painting “1000 Rockers, One Fuckin’ Bike” (2021), featuring a gathering of 1000 rocker-biker skeletons, most outfitted in black-leather jackets and sporting riding goggles. This large work, which is about 2.5 meters (roughly 8.2 feet) wide, was partly inspired, McLean has said, by the Clash bassist Paul Simonon’s exhibition “Wot No Bike,” which was shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, in London, in 2015. It featured that musician-artist’s paintings and linoleum cuts of such biker accoutrements as leather jackets, gloves, and boots, as well as goggles, helmets, and motorcycles.

Explaining his painting’s evolution, McLean recalled, “First there was the Generation X song ‘100 Punks,’ and then a friend of mine, Johnny Deluxe, presented an exhibition of the same name with 100 photo-booth portraits of punks.”

[Editor’s note: “100 Punks” was part of the exhibition “Rip It Up: Reading and the Punk Rock Revolution,” which was shown at the Museum of Reading, in Reading, England, a city to the west of London, in 2007. Organized by the artists Johnny Deluxe and Cathy McLennan, it focused on the flourishing of the punk movement in Reading in the late 1970s. It included local, punk-related memorabilia from that era and “100 Punks,” a group of photo-portraits of people who had taken part in Reading’s punk scene at that time.]

McLean added, “As for Paul Simonon, the title of his 2015 ICA exhibition came from an iconic image of a rocker wearing a motorcycle jacket with an image of a tiger head on the back and the words ‘Wot no Bike!’ written above it. It triggered in me the thought that Simonon could afford to have a bike, but many others couldn’t, especially unemployed punks. Leather jackets might have been affordable, but bikes certainly weren’t. I started thinking about the nature of success and how every endeavor needs a bit of involvement from Lady Luck. For every successful band like the Clash, there are thousands of others that don’t make the grade.”

In the group’s song, “Garageland,” McLean pointed out, the Clash sing, “Twenty-two singers, one microphone. […] Five guitar players, one guitar.” Remembering that song, he said, “Thinking about it, at that point, I had the idea for my painting, and it’s title came easily: ‘100 Rockers, One Fuckin’ Bike.’” However, he explained, “I made some rough sketches and then started working on the underdrawing on the canvas, but after sketching 100 rockers, I realized they weren’t enough. Half of the canvas was still empty, so I decided that my title would have to be ‘1000 Rockers, One Fuckin’ Bike!’”

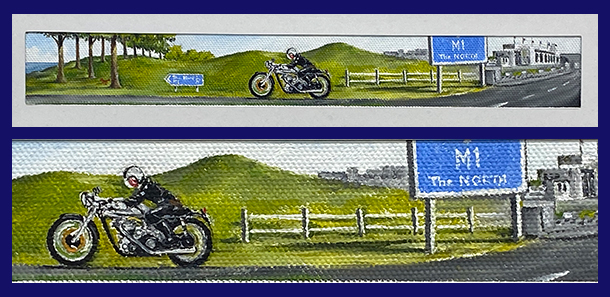

McLean worked on his big painting for two years. Meanwhile, in other single-sheet drawings and many other small works on paper or canvas, he continued developing his biker skeletons. More recently, though, after wrestling with the demands of a complex composition rendered in a large format, he produced a group of very small, oil-on-canvas paintings, each of which measures just 3 by 23 centimeters (1.18 by 9.05 inches). They became his “Edinburgh Burn-up” series.

About these small paintings, he told us, “I had started making some miniatures inspired by the Scottish poet Robert Burns’ verses, and also some landscapes of Scotland, at which point I decided to paint the landscapes in color. When I was preparing work for this exhibition, I took a cue from a scene from ‘The Leather Boys,’ a British biker movie from 1964, in which someone suggests going on a ‘burn-up’ to Edinburgh. So I decided to paint a linear narrative depicting the journey from the Ace Café in London, a legendary bikers’ hangout, to Edinburgh Castle. Because I had been doing the miniatures in color, I thought I’d continue using color for this new series.”

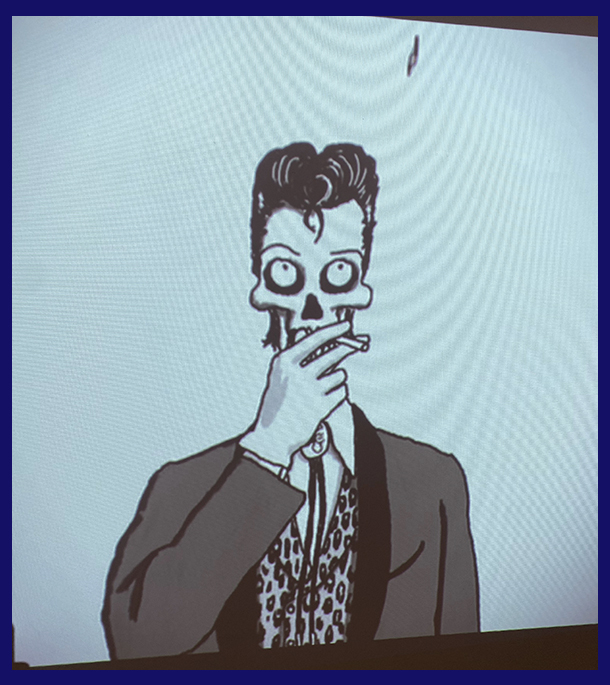

McLean, who is well tapped in to Tokyo’s underground scene, with its overlapping communities of artists, musicians, fashionistas, and hipsters, is also showing some life-size, biker-skeleton portraits and an animation reel featuring these characters in leather jackets or boxy zoot suits.

Given that, in his current JPS Gallery exhibition, McLean’s work in various media and formats and the ideas that have shaped them all seem to come together in a neatly synthesized expression of his artistic vision, we dared to pose a question not all artists feel too keen about answering: How is it that McLean regards or feels this now well-evolved creative vision, and, with the well-developed body of work he has produced, what might he wish to communicate to his audience?

He replied, “I’m interested in conveying messages through images that can be easily recognized and related to by the viewer. The story is important, but in my work, often, fragmented and isolated scenes of various activities people engage in play out against landscapes that don’t really follow the rules of composition and perspective. Nevertheless, viewers may feel comfortable with them.”

He observed, “In the images I create, the ‘activities’ people engage in can be absurd, violent, humorous, banal, imaginary, real, or surreal. I use a selection of classic characters — the screaming baby; the circus strong man; the big-bosomed, blonde dolly bird; and the fat, oily-haired salaryman. They’re stereotypes that, today, might sometimes be viewed as ‘politically incorrect.’”

McLean noted, “Still, I enjoy painting and drawing these characters, so, for me as an artist, it’s about self-satisfaction and finding a way, through my art, of processing what it means to live in a strange world of beauty and ugliness, intelligence and stupidity, violence, kindness, fear and calmness. It’s good fun!”