IN NEW WORKS NOW ON VIEW AT KAPOW GALLERY, NAOTO NAKAGAWA EXPANDS THE HUMANISTIC THEMES OF HIS MOST RECENT PAINTING SERIES

Published on February 2, 2026

“Naoto Nakagawa 2026”

Kapow Gallery

23 Monroe Street

New York NY 10002 USA

by Edward M. Gómez

NEW YORK — If, as the old adage proposes, every life is a journey or, at its most unpredictable, an adventure, then true artists’ lives represent a kind of travel that can take them to the farthest reaches of the imagination and the most restless regions of the soul.

For more than a decade now, the Japanese-born, New York-based artist Naoto Nakagawa has been packing into his paintings an endless smorgasbord of references to intellectual and cultural history, from scientists’ understanding of cosmology and the national flowers of every country in the world to the invention of the atomic bomb, William Blake’s “The Ancient of Days,” James Montgomery Flagg’s famous U.S. Army recruiting poster, swarms of migrating monarch butterflies, the pop singer Madonna in her Jean Paul Gaultier-designed cone bra, and more.

In a first group of about 16 paintings collectively known as the “Earth Series” (2013-2025), Nakagawa, who was born in Kobe in 1944 and moved to the United States in 1962, dared to think big and with sharp focus at the same time, taking the Earth, a mere dot in the vastness of the universe, as his thematic starting point.

Nakagawa allowed his pictures to find their individual and collective forms, their subjects, and their shared voice according to their own impulses, in their own time. He reveled in each new development as they evolved, like, for example, the point at which his luxuriantly depicted, blue jewel of a planet became a giant bonbon descending a staircase.

Like Marcel Duchamp’s famous, abstracted, energetic nude, Nakagawa’s Earth shakes up his compositions; it’s a curious motif, to be sure, but in the context of the image cornucopias his “Earth Series” paintings serve up, somehow, it works as many a picture’s focal point and anchor. Nakagawa’s stair-skipping Earth is a potent symbol of humanity’s home — and of the enduring force of life itself.

In time, the artist’s “Earth Series” spawned his “Mona Lisa Series” (2017-2021), most of whose 28 canvases are the same size as that of their inspiration, Leonardo da Vinci’s indelible masterpiece, which hangs in the Louvre. (For that museum, the original painting checks in at approximately 77 centimeters tall by 53 centimeters wide, or 30.32 by 20.86 inches.) Three of the paintings in Nakagawa’s “Mona Lisa Series” measure 132 by 104 centimeters, or roughly 52 by 41 inches.

The Italian Renaissance master’s iconic damsel, with her enigmatic smile — is it even a smile? — turns up in every one of the paintings in Nakagawa’s series, here with her chest’s bones X-ray-exposed, there with a fireworks display, and in assorted other iterations, with skin made of bright-green grass, a close-up of the burning Sun, a group of students walking away from a school shooting, and the seated, berobed justices of the U.S. Supreme Court.

In all of these pictures, Nakagawa’s Mona Lisa is an unflappable watchwoman, a keen observer from her perch in a painted mirror of and window on the world of the endless pageantry and pathos of the human comedy. From Nakagawa’s paintings, as from the look of Leonardo’s iconic original, one gets the idea that she could stare out from these pictures — piercingly, omnisciently, silently, contentedly — for millennia to come.

Nakagawa keeps up with the unfolding news of the world, however dispiriting it may be. During the stress-filled years of the coronavirus pandemic, he was painting away; it was during that period that he produced some of the largest works in the “Earth Series.” Since both that group of pictures and the “Mona Lisa Series” serve simultaneously as repositories and reflectors of countless aspects of human thought, invention, and history, inevitably, such contemporary markers as Russia’s war-making in Ukraine, QR codes, and references to AI made their ways into Nakagawa’s compositions.

His big challenge as an image-creating artist: How do you paint the Zeitgeist? How do you give tangible form to something as ineffable as consciousness itself?

Now, in an all-new group of paintings he has been making since early last year, when he presented his last solo exhibition at Kapow Gallery in downtown Manhattan, on the eastern edge of Chinatown, Nakagawa has retooled his symbolism. Once again, his new works, which bear no special, collective title, seem to have emerged naturally from their immediate predecessors. They mark an extension of the thinking he has long been doing about the subjects that seize his imagination, not a shift away from it.

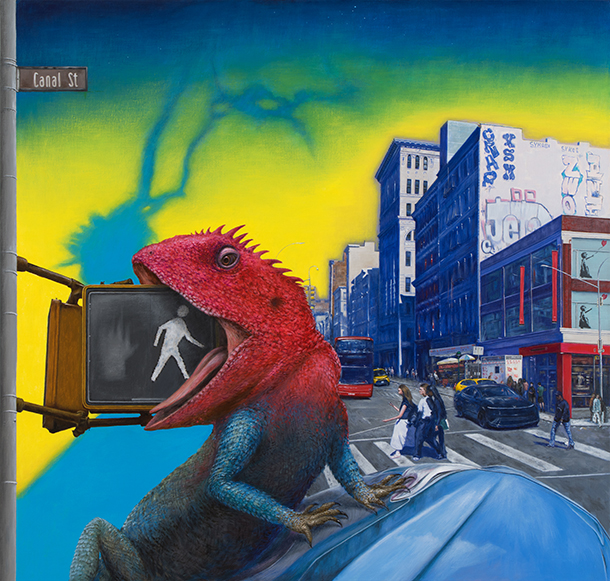

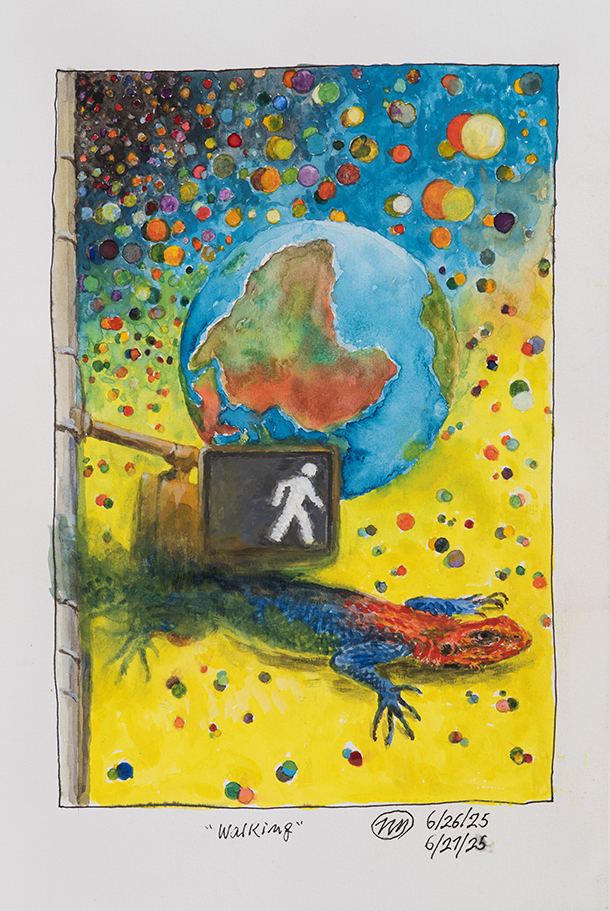

In a recent interview, Nakagawa told brutjournal, “As I developed the new paintings that are now at Kapow Gallery, as far as my imagery was concerned, I decided to go local this time. So, in these paintings, you see some clearly visible references to New York City, where I’ve lived for more than 60 years, like the view of Canal Street and the Canal Street sign in one, and a view of skyscrapers, looking up an avenue at night, in another.”

And what’s with the giant lizard with a blue body and a fiery red head that can be seen devouring an illuminated, pedestrians’ sign box at a Canal Street intersection and hugging the hood of a car as it races through Manhattan?

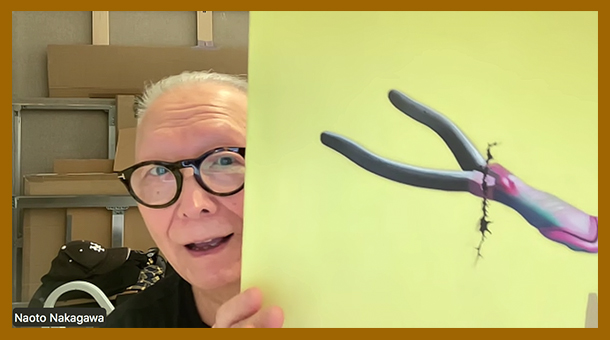

Holding up a small canvas showing a pair of metal pliers whose tool end morphs into a lizard’s head, the artist explained, “In fact, I’ve been painting lizards since the 1960s, as in this picture from 1966. When I first came to New York, I discovered the writings of [the Canadian philosopher and media theorist] Marshall McLuhan, who discusses how, by creating tools, humans were able to develop civilization and culture, and the world changed. Today, we have artificial intelligence. We’ve handed our brain power over to a powerful technology that will radically change human life again.”

He added, “At the same time, we have wars, disease, and many other problems, many of which are human-made. For me, the lizard, small or large, is a symbol of survival. This animal, which still exists today, is a descendant of the dinosaurs that went extinct after an asteroid struck the Earth 66 million years ago. So, for me, the lizard serves as a symbol of survival. I do believe that we humans will make it through these hard times — that, somehow, we will survive.”

Nakagawa’s interest in humankind’s survival in the face of all the destructive meshuggaas it has cooked up over many generations, and especially in modern times, finds symbolic expression in other ways, too, in some of his other recent images.

On view now at Kapow Gallery, for example, are several paintings and related, preparatory drawings (in watercolor on paper) showing human sexual organs melding with everyday objects; formally, in terms of the strange imagery they serve up, these pictures hark back to Nakagawa’s image-making experiments decades ago, like his surreal pair of pliers with a lizard’s head.

Nakagawa told me, “I wasn’t thinking of shunga when I made these new paintings; it was Kourosh Mahboubian, the owner-director of Kapow Gallery, who mentioned that old genre of Japanese erotic art, which took the form of woodblock prints and were popular in the Edo period [1603-1867]. In fact, this is what I was thinking, which led to these paintings: I was thinking about how we’ve created nuclear weapons and ChatGPT. We’re not human anymore. Will AI have the ability to create its own, new kind of AI?”

The artist added, “If so, and if it makes a mistake, could something happen that would cause all of us to die? The functions of our brains and the content of our minds might have been downloaded into AI, but there’s still something we do and that we like that shows that we’re still human. That is sex. These new paintings refer to that basic human impulse. We’re animals. We have emotions. We’re not machines.”

Expanding on such fundamentally humanistic thoughts, Nakagawa referred to Francisco Goya’s painting “The Third of May 1808” (1814), which shows Spanish resisters of Napoleon’s occupying armies being executed by a firing squad of the French emperor, with one white-shirted rebel throwing up his arms as he faces his killers. Nakagawa also cited Pablo Picasso’s mural-size painting “Guernica” (1937), which shows a Basque village’s pained reaction to a bombing raid by the Spanish fascists’ German and Italian allies during Spain’s civil war.

The New York-based painter said, “At our current moment in history, when I think about what the role of an artist in society can or should be, I think about how, in those well-known paintings, Goya and Picasso showed what the world was going through in their times.” Those pictures, he noted, imply or directly depict the effects of certain forces that had been unleashed at different times in the past.

Nakagawa said, “I’ve spoken to other artists. I’ve noticed that, through their work many of them are not responding to what’s happening today. All of us artists — we love the freedom we have in which to create. For me, my response to what’s happening — I think I’m expressing it with a message about survival. I really do believe that we’ll pull through this period and survive.”

Nakagawa recalled the turbulent years of the 1960s and the 1970s in the United States, which were marked by political assassinations and such incidents as the Ohio National Guard’s killing of four unarmed students on the campus of Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, on May 4, 1970.

Referring, in his succinct way, to the whirlwind of corruption, criminality, mendacity, violence, war-making, and hostility against American citizens and residents of the USA that has become the main hallmark of the Trump regime, Nakagawa said, “I’ve seen much of this before, and, although it took some time, we got over it. I remember, in the 1960s, going to anti-war protests with Yayoi Kusama, Kate Millett, and Fumio Yoshimura, who was Kate’s husband at the time. One time, Kate brought a toilet seat and an American flag to a demonstration and set them up to make it look like the flag was being flushed down a toilet.”

“We survived before,” Nakagawa observed. “I believe we’ll survive the current moment, too. In my new paintings, I’m not referring only to the U.S.A.; with my message about survival, I’m referring to the world.”

A few days after our interview, by e-mail, the artist and I exchanged messages for the purpose of fact-checking the identifying data for some of the artworks that are reproduced here.

In one of his messages, Nakagawa, who, during our earlier interview, had noted that he is as busy as ever today, at the age of 81, wrote, “Thank you for your questions about my painting’s long journey.”

Below, an earlier painting from the “Earth Series” by Naoto Nakagawa: “The Last Supper,” 2014, acrylic on canvas, 55 x 84 inches (139.7 x 213.36 centimeters). Photo by John Berens, courtesy of Naoto Nakagawa