A YOUNG ARTIST WHO HAS MADE NEW YORK CITY HIS HOME HAS BEEN DEVELOPING HIS WORK OUTDOORS, IN A POPULAR PARK

Published on November 19, 2025

by Edward M. Gómez, with Ashton Herres

It’s no secret that the cost of living in New York City is exorbitantly high, with prices for food and the rent for even a broom closet of a living space (also known as an apartment) making it prohibitively expensive for young people — or anyone else — to make their way there to chase their dreams of fame, fortune, power, or pleasure. Nevertheless, newcomers do still keep arriving, settling in, learning their street smarts, and putting together the essential components of a New York life.

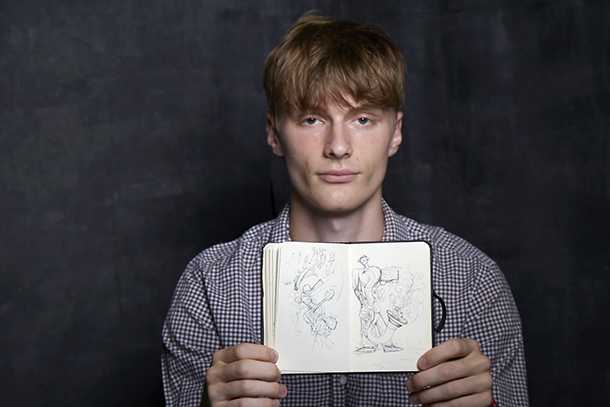

Now 20 years young, Ashton Herres, who made his way to the city from New Hampshire about two years ago, is still a relatively new New Yorker — one who knows exactly why he made the big move.

Recently, he told brutjournal, “I was motivated by the promise of new experiences and the energy that only a city like New York can offer.” He added, “I was [also] driven by a deep fear of complacency — the sense that if I didn’t move, I’d become trapped by the smallness of my environment and the predictability of routine.”

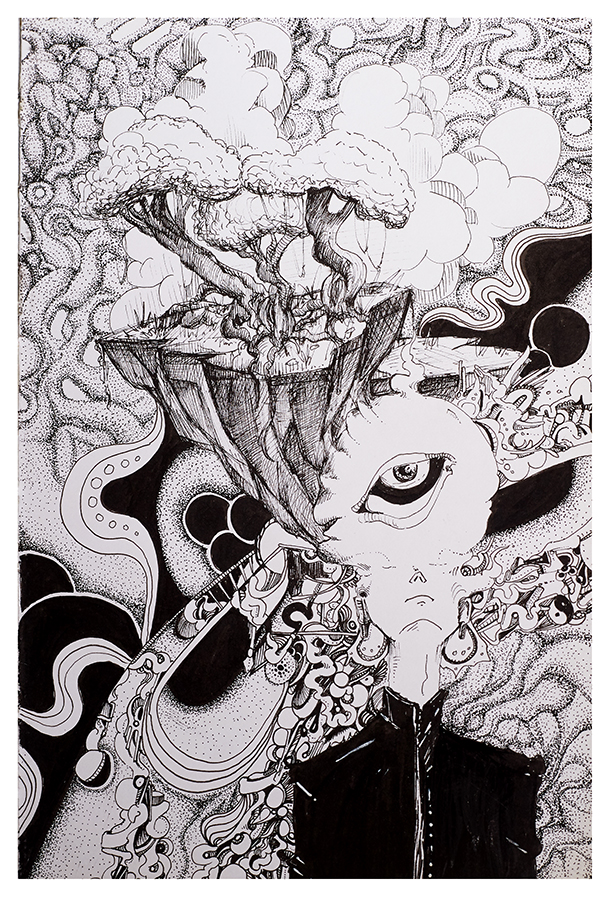

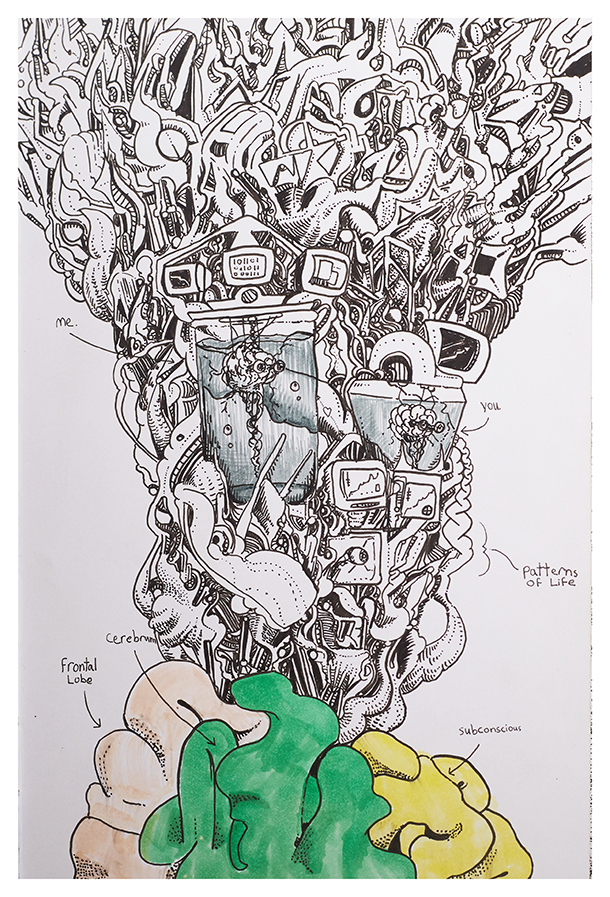

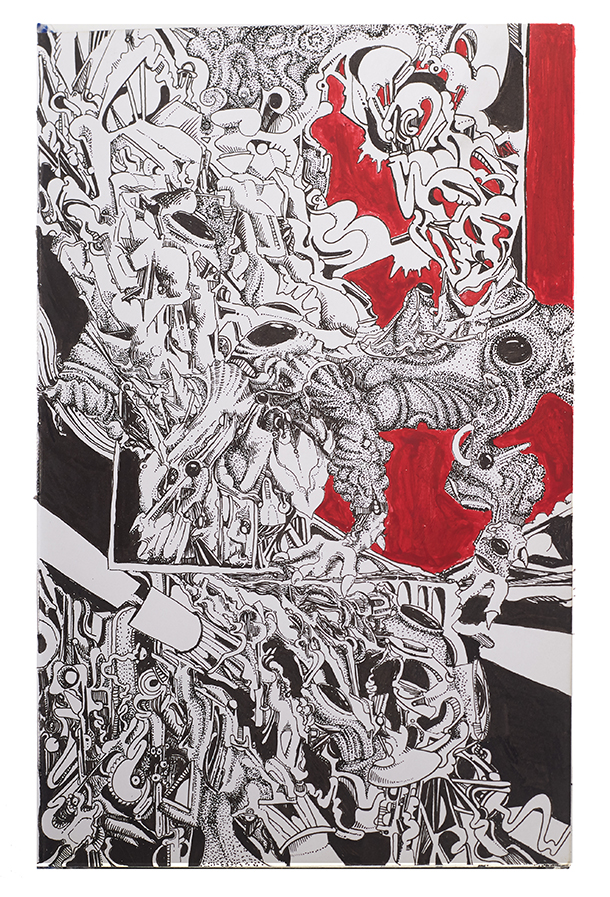

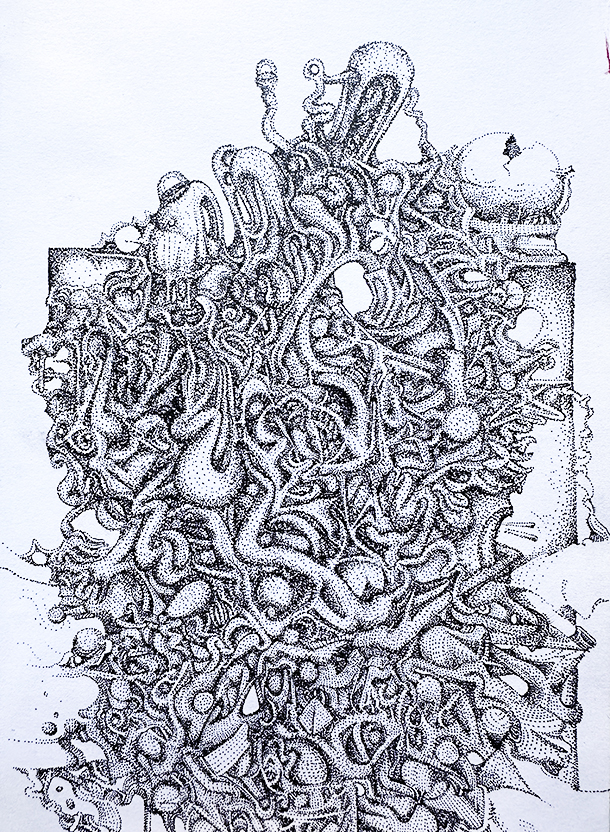

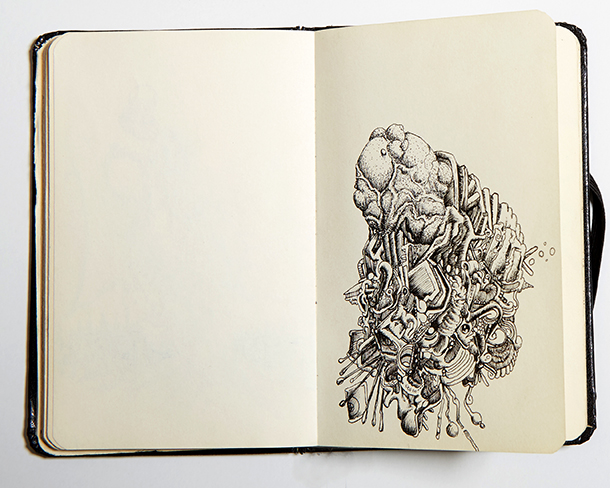

A few months ago, during one of his regular walks through Washington Square Park in downtown Manhattan, brutjournal’s visual director, the photographer Bill Westmoreland, spotted a young man drawing in a sketchbook and displaying some of his single-sheet works, which appeared to be for sale. He struck up a conversation with the artist — it was Ashton — and asked him about his unusual-looking pictures, in which such subjects as trees and spongy sections of brains appear in compositions densely packed with what appear to be self-generating mechanical parts and unidentifiable, vegetal or animal-tissue growth.

In one picture, a briefcase-carrying man whose entire body feels impossibly elastic and fluid strides forth with an awkward gait; in another, a gang of colorfully costumed humanoids fills a graffiti-lined subway carriage along with an enveloping jumble of unfurled cables, assorted spherical objects, and some disembodied eyes.

Bill recalled, “Right away, I sensed that Ashton’s drawings were good examples of the kind of art we’re always excited to discover; our chat led to a photo session and an interview.”

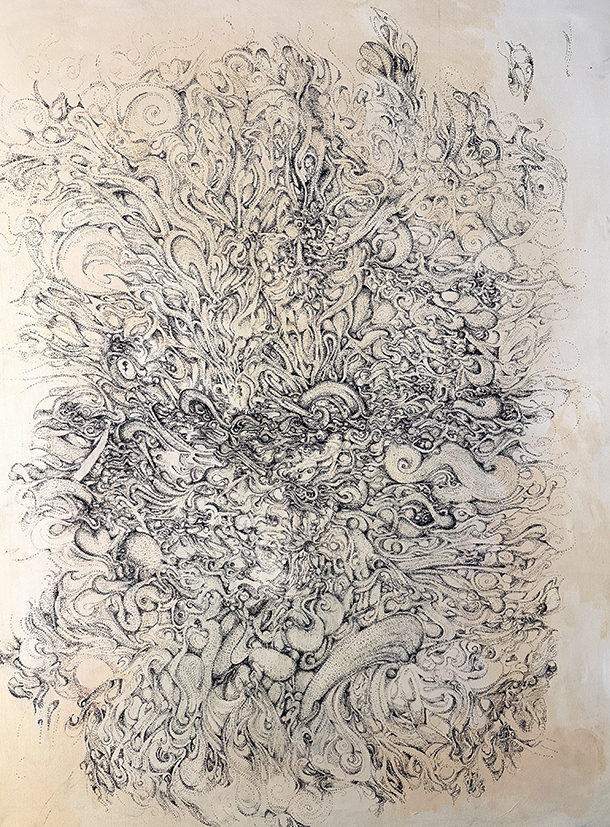

We were intrigued by the character and content of Herres’s drawings, and also wanted to know when and why the young artist had begun making them. He told us, “I began drawing seriously when I was seventeen. I’d dabbled before, but around that time, I felt a distinct obsession forming — a fixation with creating textures through line. Drawing became a meditative ritual, a way to explore and externalize my own introspective curiosity.”

Noting that he feels he has been influenced by the works of many different artists, he also has been greatly inspired by his art-making friends. Among his other influences: sci-fi movies, jazz music, and literature. (As far as artistic affinities are concerned, in some of Herres’s drawings, one may notice something of the funky, rollicking energy of the abstracted forms that appear in many of the painter Philip Guston’s rumbling compositions.)

So what’s going on in his pictures? What or who are the fantastical creatures that appear in them, and what are viewers to make of the expanding thickets of ectoplasmic material that command so much space in his complex compositions?

Herres explained that he depicts “scenes and figures that exist in the gray area between the fictional and the real,” and added, “Most of my work is drawn intuitively, channeled from the subconscious; it’s less a deliberate depiction of something external and more a snapshot of my internal state during its creation.”

To be sure, his drawings do convey a sense of creative impulsiveness. They also exude an energy that feels subversively berserk. Herres said, “Blending human form with abstraction is my way of merging emotion with pure visual texture — of translating feeling into form. [To me,] my line work feels like the texture of my mind; sometimes it feels as if I’m drawing the folds and interconnectivity of my own brain tissue.”

We wanted to know about one of the mark-making techniques that is visible in some of Herres’s drawings. That’s his use of agglomerations of small dots to create lines or to produce the illusion of round, tubular, or expanding forms.

The artist said, “This stippling technique is the most reflective and meditative form of self-portrayal I’ve found. There’s something about phasing in texture through single black dots that feels deeply accurate. It produces these smoky, atmospheric renderings that, to me, mirror the quiet turbulence of the mind in motion.”

Speaking of the mind in motion, we were curious to find out how Herres feels about taking his art-making activity outdoors and offering a kind of live performance that, inevitably, may draw the attention of passersby, even in a park in which the daily pageant of New York street theater provides an endless line-up of attractions. Among its cast of characters: busking musicians, jugglers, vendors, college students hanging out, skateboarders, chess players, and the occasional cop walking this frenetic beat.

Does it take a certain amount of courage to take his act out in public the way he does?

Herres said, “Maybe, but courage feels secondary to intent. Preconceptions are the enemy of action. There’s definitely a fear tied to expressing oneself publicly, but the joy and growth that come from it outweigh any moments that feel like a ‘humiliation ritual.’”

He told us, “I started experimenting with live painting and vending outdoors about a year and a half ago. At first, it was a social experiment, a way to stay engaged with people and contribute something to the community and maybe to society at large. It’s been fun, challenging, and rewarding. The biggest challenge is the physical strain, but it’s offset by the generosity of strangers. Most people are far kinder than they’re given credit for, especially toward those taking [such] social ‘risks.’”

He said, “I’ve had countless conversations with passersby. Sometimes they’re short and transactional and other times profoundly meaningful, like two comets briefly crossing orbits before drifting apart again. I’ve seen people pulled out of their phones or bad moods by seeing my drawings, and that moment of connection always leaves me smiling.”