“OUTSIDER,” A NEW DOCUMENTARY FILM, CHRONICLES THE DISCOVERY AND FIRST PUBLIC SHOWING OF A CLOISTERED ARTIST’S EXUBERANT WORK

Published on November 17, 2025

by Sarah Fensom, brutjournal’s U.S.A. West Coast bureau chief

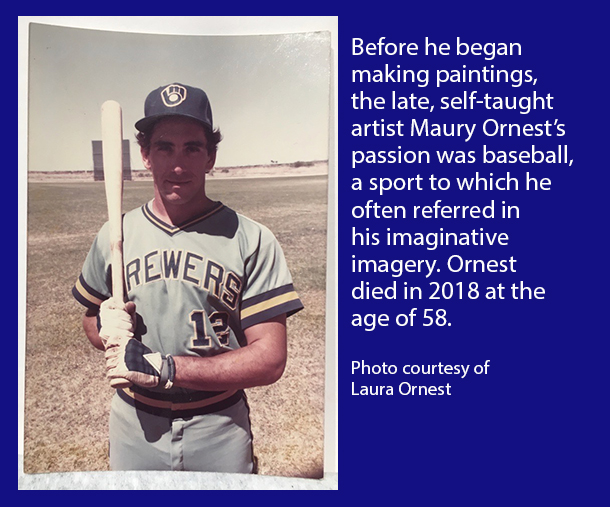

LOS ANGELES — Maury Ornest, a self-taught artist who was born in 1960 and lived in Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, died in 2018 at the age of 58. His sister Laura Ornest, an award-winning broadcast journalist, knew that her brother was a painter but what she discovered following his death — a cache of many hundreds of artworks — was an eye-opening revelation.

In an interview with brutjournal earlier this year, Laura recalled, “We went into the house, and it was shocking to see all the paintings. Every room in [his] one-story, three-bedroom house was filled with paintings — stack after stack after stack.”

In Maury’s garage and in multiple storage units she didn’t even know her brother had been renting, she found even more paintings and sketchbooks. Subsequently, after spending many months combing through his home and cataloguing all the art he had left behind, Laura’s inventory of Maury’s works totaled 1400 paintings and more than 100 large sketchbooks.

For several decades prior to his death, Maury Ornest had struggled with mental illness, often isolating himself from his family. While Laura was aware that her brother had taken up painting when he was in his late twenties, she was surprised to learn just how prolific and dedicated to art-making he had become, and how striking his work had turned out to be. Making art, it appeared, had become the substance and purpose of Maury’s life.

As his immense output came into focus, Laura set out to realize what she learned had been her late brother’s dream: to exhibit his art publicly for the first time.

Laura said, “How could you not do something with this gift that [Maury had] left? How could you not try to see if it could be appreciated by [other] people?”

As she sorted through Maury’s artworks, she hired Paige Wery, the director of Tierra del Sol Gallery, to help her curate an exhibition of a selection of her brother’s paintings, which was presented at his home in February 2019. (Located in L.A.’s West Hollywood district, Tierra del Sol Gallery is associated with the Tierra del Sol Foundation, which supports an art-making and exhibition program for disabled artists). Remarkably, visitors to that first-ever showing of Maury’s works purchased some 300 paintings; a total of roughly $83,000 earned from those sales was donated to several different charities.

While Laura worked on that inaugural presentation of her late brother’s art, her friends encouraged her to document her activity. Buoyed by their enthusiasm, she reached out to two longtime family friends, Ted Haimes, an accomplished documentary filmmaker (Duane Michals (1939-1997) (1978); Hitchcock: Shadow of a Genius (1999)), and his wife and producing partner, Nicole Lucas Haimes.

Laura’s first step was to invite Ted to take a look at Maury’s paintings. She recalled, “Ted fell in love with the work and was very impressed. He seemed like the right person [to whom] to entrust this story.” Little by little, the idea for a documentary film about Maury Ornest’s career as an artist took shape.

Ted Haimes, who observed Laura as she worked on the 2019 exhibition, stepped loosely into the budding film project. He said, “We didn’t have a plan or a film in mind. It was just that there was a moment in time that felt fragile. I put a camera on my shoulder and shot stuff.”

Haimes’s initial, free-form shooting turned into Outsider, a new, 40-minute documentary about Maury’s life and art that already has been screened at the Portland Museum of Art in Maine; Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine; the University of California Santa Barbara; and several other venues around the United States. Outsider brings together interviews with Maury’s family members and friends, archival photographs and home-video clips, readings from the artist’s journals by the stand-up comic and actor Gary Gulman, and copious footage of Maury’s paintings and drawings.

The film feels both gut-wrenching and hopeful as it recalls how the late artist struggled, living with mental illness, and also evokes the healing, expressive power of art-making, which he enthusiastically embraced.

As is the case with numerous other self-taught artists, for Maury Ornest, art was not his first passion. Instead, baseball was his life. He came from a affluent, sports-focused family, and possessed the kind of natural athletic talent that caught the attention of Major League Baseball scouts when he was still a student at Beverly Hills High School in 1977. He opted to play college baseball instead, becoming a standout player at U.C. Santa Barbara before being selected in the third round of the 1980 draft by the Milwaukee Brewers. Recalling that one of her brother’s girlfriends at the university, an art student, once told her that she could never coax Maury off the baseball diamond and into an art gallery, Laura said, “He was a jock. It was all about baseball.”

In 1982, some time after leaving UCSB and while playing in a minor-leagues game, Maury slammed against a cement outfield wall. The injuries he suffered from that fateful accident put an end to the young athlete’s baseball career. Not long thereafter, Maury began experiencng paranoid delusions; he had trouble regulating his moods and handling his personal relationships. His charming affability, for which he had been known, began to fade, although sometimes it still shone through. Maury’s condition had a name: ultimately, he was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder.

Art entered his life as a means of healing. Laura noted that, when her brother was in his late twenties, one of his therapists suggested that he start painting as a way of expressing himself. That was after Maury had experienced a psychotic break (a sudden episode of psychosis involvng a loss of contact with reality). For a while, in L.A., Maury took art courses at the extension school of the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Otis College of Art and Design. He also studied privately with Stephanie Pryor, an art teacher at the UCLA extension school whom Maury mentions in his journals as someone who inspired him. (She appears in Outsider, recalling the self-taught artist.)

Still, despite having dipped lightly into structured art classes, for the most part, as an art-maker, Maury taught himself. Laura pointed out that her brother “read voraciously” and studied the work of such well-known artists as Jackson Pollock, David Hockney, Lucian Freud, Jean Dubuffet, and Vincent van Gogh. Inspired by and imitating certain aspects of their works, he incorporated such efforts into his own. Laura said, “He wrote about all of these figures in his notebooks. Van Gogh was [his] primary muse. He identified with his mental illness.”

Maury developed a deeply personal painting style that was grounded in his use of bold primary colors and a penchant for intricate patterns made of geometric shapes. His body of work boasts fantastical landscapes, spirited portraits, and busy still lifes. In them, he routinely returned to the subjects that fascinated him; baseballs, for example, make regular appearances in his paintings, sometimes as inanimate objects and other times with expressive faces or as parts of other creatures. Fish, birds, blimp-like flying vehicles, and hybrid flying machines also appear in his pictures, as do such art-making materials as tubes of paint, pencils, and bottles of ink.

Haimes’s docu-film shows Maury’s paintings and drawings in an energetic way, providing expansive views of his works and also zeroing in on them, roving close up to reveal their details. Haimes drew inspiration for Outsider from his own earlier film Duane Michals (1939-1997) which examines the sequential photo narratives of the American photographer who is its subject. Haimes also looked back at other projects about artists on which he had worked as he sought to identify the characteristics that distingush Maury Ornest’s art.

Haimes said, “With all the artist films I’ve done, I’ve always tried to find a cinematic version of an artist’s point of view. [Maury’s] paintings are very physical, and when you stand in front of them, you can see [him]. You can feel him standing in front of the canvas, putting on paint. He was not a quiet guy. He was a big man with a big personality, and you can see that in the movement of his paint on canvas.”

For Haimes, part of the success of Maury’s work is its ability to pull back the curtain on its maker. The filmmaker observed, “The exuberance of Maury’s personality comes through, as does his love of tickling his own eyes and his own mind; [his art’s spirit] tickles our eyes and minds, too.”

For Laura Ornest, Outsider serves as a lasting way of recognizing her brother’s art and keeping the memory of his life and achievements alive. It’s also part of a bigger picture. As she put it, “Our goal is to foster awareness of, conversation about, and compassion for those who are facing mental illness, and to help them feel less alone, because Maury was so lonely, and it was lonely for our family.”

With Outsider, she said, “We’re showing the power of art to sustain life.”