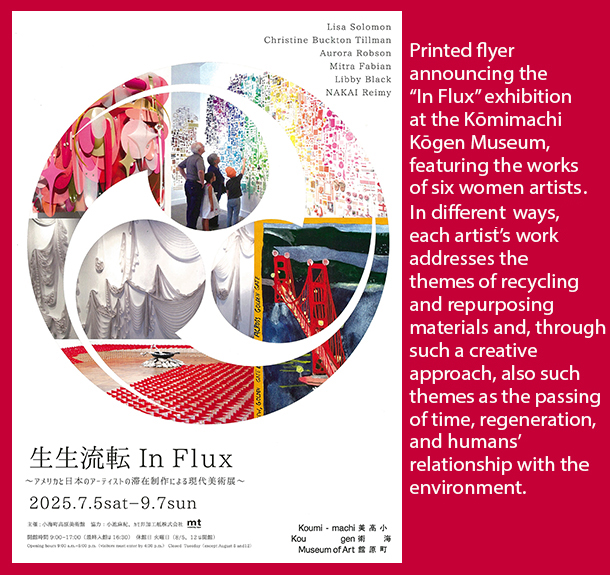

FIVE U.S.-BASED FEMALE ARTISTS AND ONE LOCAL, JAPANESE COLLEAGUE INTERPRET FOUND AND HUMBLE MATERIALS IN IMAGINATIVE WAYS

Published on August 13, 2025

by Edward M. Gómez

KŌMI-MACHI, NAGANO PREFECTURE, JAPAN — Heading west from Tokyo to Nagano Prefecture on the high-speed Shinkansen train, the pride of Japan’s vast, superb, national transportation network, a traveler changes trains at Sakudaira for a laid-back local/regional line that takes a scenic route to the small town of Kōmi-machi. It’s situated on the banks of the Chikuma River in the far eastern part of Nagano, in the Yatsugatake Mountains region, which is known for its thriving agricultural sector and tourist-attracting natural beauty.

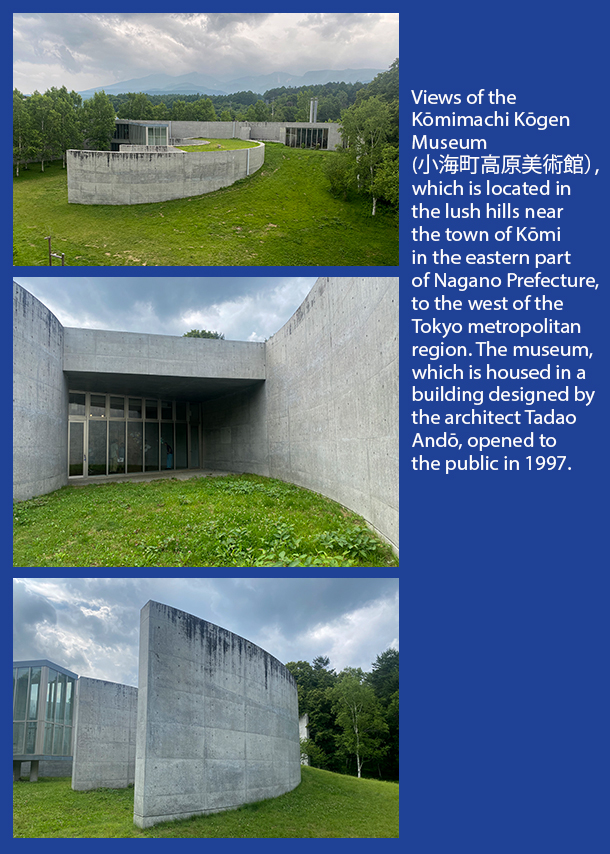

Among other attractions, Kōmi-machi is home to a small but ambitious contemporary-art museum that has established a reputation for imaginative, original programming. Opened to the public in 1997 and housed in a signature, poured-concrete building designed by the Japanese architect Tadao Andō, the Kōmi-machi Kōgen Museum is located in the hills on the outskirts of the town. It can be reached by car, or by bus or taxi from the town’s train station, in about 20 minutes. Hardy visitors willing to tackle some steep hills can make the trek by bicycle.

As travelers often discover in Japan when making their way to places off — or even way off — the art-and-culture scene’s well-beaten path, there are rewarding pay-offs for those who dare to explore a wide terrain. In this case, an onsen (hot spring) may be found right next door to the museum.

In early July, the Kōmi-machi Kōgen Museum unveiled its newest exhibition, “Seiseiruten • In Flux,” which features works created by six female artists, five of whom are based in the United States, and one of whom is Japanese, based in Japan. They include, working as a team, Lisa Solomon, from Oakland, California, and Christine Buckton Tillman, from Pikesville, Maryland; Libby Black, from Berkeley, California; Mitra Fabian, from San José, California; Aurora Robson, a Canadian based in the Hudson Valley region, in western New York; and Reimy Nakai, who lives and works in Nagano Prefecture.

“Seiseiruten • In Flux” explores several related themes. Central among them: how artists imaginatively reuse, recycle, and repurpose found and cast-off materials, often items that are far from the usual stuff of art-making and that, as Aurora Robson, who uses plastic bottles, bottle caps, and other plastic trash to create her vivacious assemblage sculptures says, “have been rescued from the waste stream.

As the exhibition’s accompanying gallery guide notes, it looks at how its featured artists “reinterpret [their] materials against the backdrop of various social issues and personal histories,” thereby creating new settings and contexts in which viewers of their works may “notice the beauty in the everyday and the extraordinary nature of objects” they employ to give form to their creative visions.

The current exhibition emerged out of Lisa Solomon’s discussions with the Japanese museum’s director, Junichi Natori, and one of its curators, Minoru Nakajima, which began several years after she took part in another group show at the museum back in 2007. That earlier exhibition, “Currently West,” featured works made by six artists based in the western part of the U.S.A.

Rounding up a group of like-minded artists who shared aesthetic, technical, and philosophical interests in creating art using cast-off materials (and in working on site to do so) rather than using all-new, store-bought supplies, Solomon collaborated with the museum’s curatorial team to develop “Seiseiruten • In Flux,” which opened on July 5, 2025.

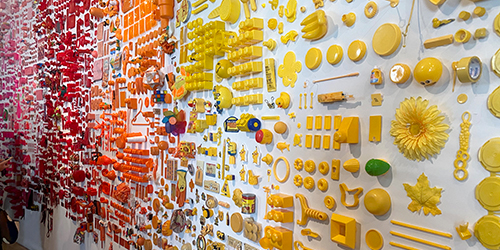

Given the relatively free flow of the museum’s exhibition galleries on two floors that are connected by stairs, an elevator, and a long ramp, visitors may start exploring the works on view from various vantage points. Covering the billboard-wide expanse of a tall wall in a large, ground-floor room, Solomon and Tillman’s “Chroma” commands its space with a spectacular display of wall-mounted, mostly plastic packaging and toy parts, kitchen tools, odds and ends, and whatchamacallits.

As exercises in found-object assemblage art-making go, “Chroma” is about as big, ambitious, and audacious as its gets. This is a work of contemporary art that makes its point again and again, insistently and repetitively, but joyously and dazzlingly, too, as it calls attention to and celebrates each of its humble components and, at the same time, the monumental sum of its parts.

Look closely to see how it packs in everything, in separate, color-themed sections that blend seamlessly into each other, from the purple-plastic battery compartment from some long-forgotten, broken appliance to a blue toy truck and blue caps from bottles of Aquarius, a popular Japanese energy drink; giant Lego bricks, artificial flowers, and a rubber ducky (in the yellow section); eyeglass frames, a roll of tape, and a tiny hairbrush (in the green section); and a small padlock, a pinwheel, and a smiling monkey (in the pink-red section), among many other resuscitated treasures.

If “Chroma” feels a bit daunting, that’s because it is; it’s also one of Solomon and Tillman’s signature productions, which, over the years, they’ve created several times for various venues. Prior to the exhibition’s opening date, residents of the Kōmi-machi area were invited to contribute cast-off items for this work and for Robson’s pieces, too; in response, the museum received large quantities of donated materials which the artists enthusiastically used.

Solomon told guests at the exhibition’s opening, “If you gave us stuff, it’s here now, on the wall!” Separately, she told me, “Each time we create ‘Chroma,’ it becomes something new and different, depending on what we have to work with. Measuring 17 meters long, this is the biggest version we’ve ever made; we were thrilled to be able to produce it here, for it has been our dream to be able to make and present this piece in Japan.” Most of the elements on view in this latest version of “Chroma” came from Japanese donors, but Solomon and Tillman also brought a supply of favorite materials with them from the U.S.A.

Robson, who lived and worked in Brooklyn before moving with her family to the Hudson Valley several years ago, has long used plastic drink bottles and other plastic trash to create her assemblage pieces. In the past, for example, she once used plastic waste washed ashore on a beach in Hawaii, where she grew up, to make a large sculpture.

Their forms and textures are influenced by those of plants and other points of reference in nature. As Robson explained to me in the past, during the early years of its development, much of her art also emerged from and in reaction to her dreams. (She also makes paintings and meticulously crafted collages using the junk-mail printed matter that arrives in her mailbox.)

At the museum, Robson said, “To make my works for this exhibition, I used both donated materials and some items I brought with me from my studio. I clean my plastic raw material and airbrush the pieces I’m going to use with non-toxic paint. I also use a plastic welding technique that allows me to sturdily join together the pieces that make up each artwork. Plastic pollution is a worldwide problem. Plastic doesn’t degrade fast and is going to be around for a very long time. So I think it’s better to try to make something beautiful with plastic trash.”

About the installation work she created (“Rise and Fall”), which hugs and stretches out beyond a large wall, the artist Mitra Fabian explained, “I wanted to work with a material that is uniquely Japanese, so I chose colored masking tapes, which are very popular here. The tapes you see in my work are the ends of several rolls; they’re the byproducts of the manufacturing process — a different kind of garbage.” For Fabian’s site-specific creation, mt, a Japanese company that manufactures and markets masking tapes and other products, donated more than 200 rolls of tape for the artist’s use.

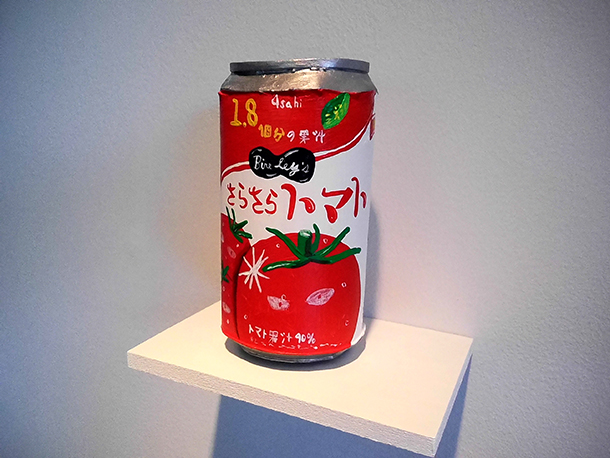

Libby Black uses paper, glue, and paint to make replicas of real, often familiar objects, such as a bouquet of flowers, a can of tomato juice, or a short, Japanese-style broom. Before arriving in Japan, she noted, “I was thinking about the kinds of postcards that are sold in museum gift shops, so some of the works I created for this exhibition are postcards whose subjects are related to the Bay Area of northern California, where I live, and also to Japan, like Hello Kitty or the butterflies you see here in the Kōmi-machi area.”

For the exhibition, the artist Reimy Nakai, who is interested in history, Japanese mythology, and hunting has created a small boat adorned with a piece of fur and bones from one of the animals she has killed. Her work “Hiruko’s Boat,” she explained, evokes the ancient myth of the Japanese deity Hiruko, according to which this firstborn son of the creator deities Izanagi and Izanami is set afloat, alone, in a small reed vessel, for his body is deformed, with undeveloped limbs. Later in Hiruko’s story, he becomes identified with Ebisu, the god of fishermen.

About the exhibition’s main theme, its curator, Minoru Nakajima, told me, “Waste and pollution — today, everywhere, these are worldwide concerns. Recycling and repurposing cast-off materials can help protect the Earth. Now, how can art address and express these ideas? Here, in the ways in which these artists think about and uses their materials, they respond to this question.”